To that end, the Native American Agriculture Fund partnered with the Indigenous Food and Agricultural Initiative and the Food Research and Action Center to produce a special report, Reimagining Hunger Responses in Times of Crisis, which was released in January.

According to the report, 48% of the more than 500 Native respondents surveyed across the country agreed that “sometimes or often during the pandemic the food their household bought just didn’t last, and they didn’t have money to get more.” Food security and access were especially low among Natives with young children or elders at home, people in fair to poor health and those whose employment was disrupted by the pandemic. “Native households experience food insecurity at shockingly higher rates than the general public and white households,” the report noted.

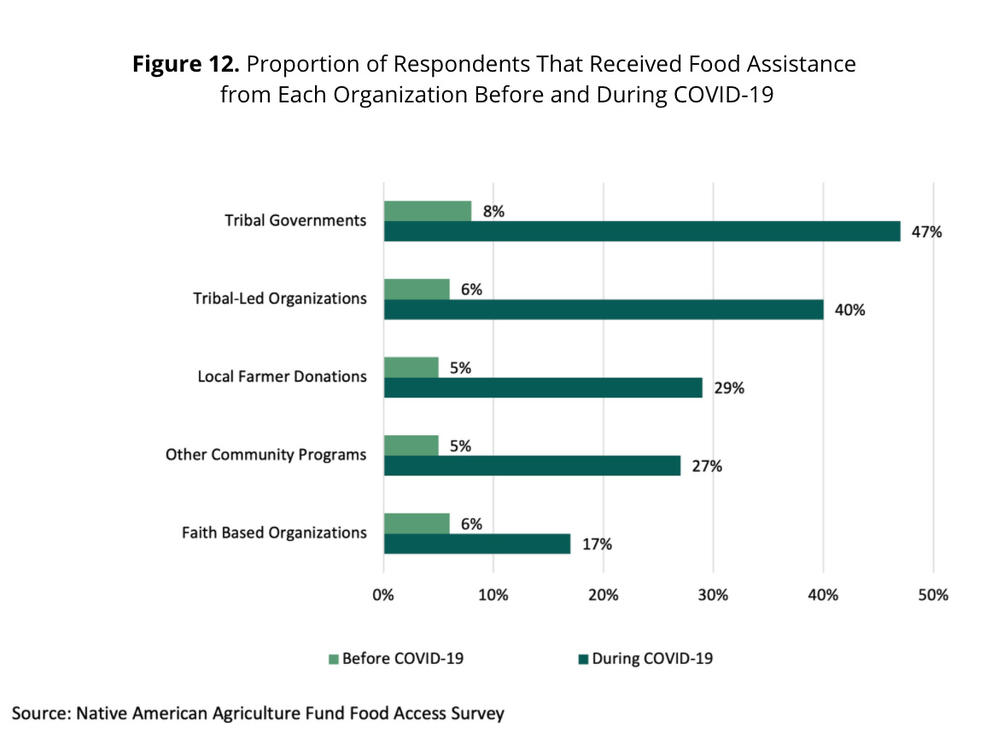

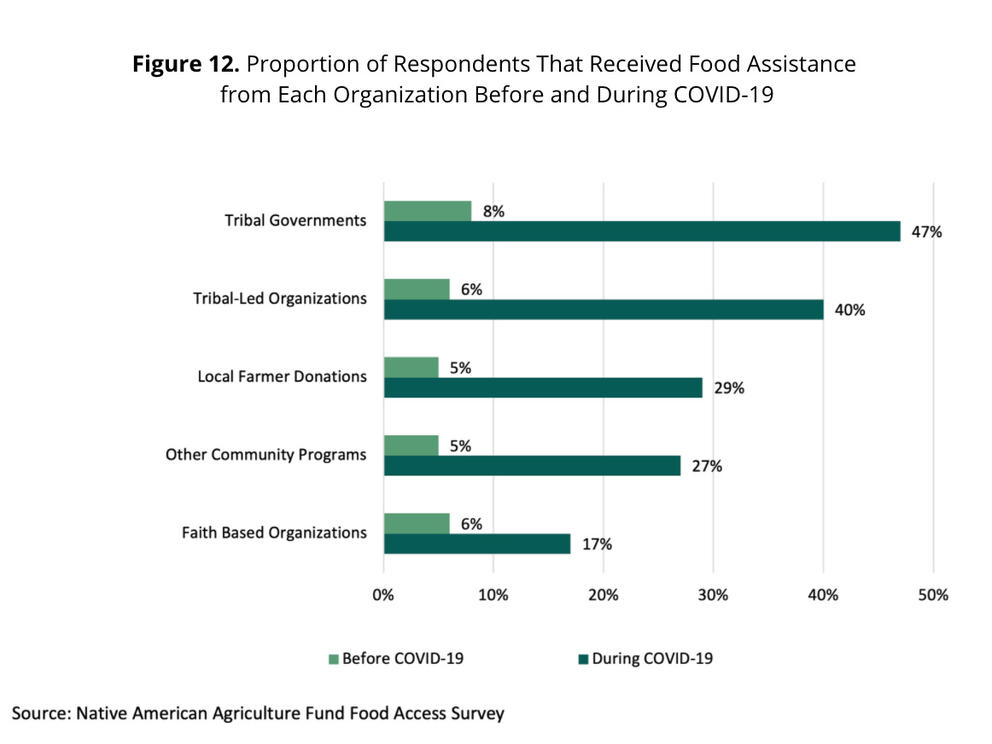

It also detailed how, throughout the pandemic, Natives overwhelmingly turned to their tribal governments and communities — as opposed to state or federal programs — for help. State and federal programs, like the Supplement Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, don’t always mesh with the needs of rural reservations. A benefits card is useless if there’s no food store in your community. In response, tribes and communities came together and worked to get their people fed.

Understanding how and why will help pave the way for legislation that empowers tribes to provide for their own people — by using federal funding to build local agricultural infrastructure, for instance, instead of relying on assistance programs that don’t always work. High Country News spoke with Toni Stanger-McLaughlin (Colville), the CEO of the Native American Agriculture Fund, to find out more.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

High Country News: The big number from this report is that 48% of Native people surveyed experienced food insecurity during the pandemic. Was this a failure of infrastructure, like supply chain issues and trucks not getting to reservations?

Toni Stanger-McLaughlin: It was a perfect storm of all of those things during the height of the pandemic. Reservations are the rural of rural — they’re oftentimes so far removed from access to transportation, or any type of processing or storage plant, that they fully rely on those systems operating in a timely manner. When they don’t, it means that those communities go without.

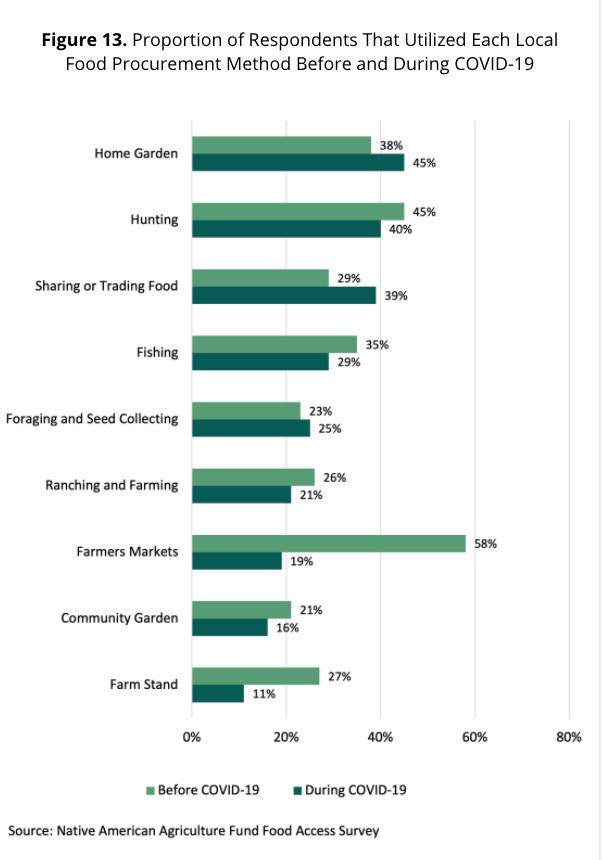

HCN: According to this report, Natives changed where they got their food during the pandemic. They stopped going to farmers markets and community gardens because of social distancing and did more home gardening, foraging and collecting of seeds, as well as sharing food. But, surprisingly, they hunted and fished less. Do you know why?

TS-M: A lot of the communities were on strict lockdown. You weren’t supposed to leave your home. Going on a couple years now, these communities are still reeling and still having to figure out what to do. We also saw a real big uptake in direct farm-to-family. You could buy a cow in your neighborhood, or in your community, where before you couldn’t. Those farmers were selling to stockyards, who were then selling to big processing plants. Your meat could go three states before it would return to your community. Instead, we saw more direct sales. And the federal government allowed that. It hasn’t happened at that scale in a long time.

HCN: The gap in food security seems to have most impacted medium-income households as opposed to the poorest households. Is that correct?

TS-M: Yeah. … When we receive this data, and we look at the income level of the respondents, that doesn’t correlate to the requirements to participate in some of the food assistance programs that exist in the federal government and then trickle down to state and tribal governments. So, for instance, to qualify for what used to be called the food stamp program, SNAP, or WIC [the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children] or free school meals, all those programs are income-contingent. And they get continued servicing.

For those that could qualify, income-wise, those programs weren’t obstructed in a way that the general food access [was] — getting a food distribution box versus going to a grocery store where everything is gone; everyone has purchased the goods from that grocery store. We saw it with toilet paper, but we saw it with food, too. There was a huge shortage of meat, or the meat was so expensive that it disabled people from being able to get the full nutritional value of each of their meals. They had to pick and choose. Those are, in our respondents in our survey, largely the ones that identified as being food insecure and lacking nutrition.

HCN: FRAC — the Food Research and Action Center — talks about opportunities to address food insecurity with the Build Back Better plan or through Congress. But your organization seems more focused on tribal efforts, saying that instead of increasing benefits, the federal government should increase support and empowerment of tribal governments. Why is that distinction important?

TS-M: Well, unfortunately, we have to do both. When we saw in the report that people were turning to their tribal governments, not their state governments, for assistance, it’s just another indication of the ability of tribes to administer those program dollars and keep an alignment with the requirements and mandates that come from receiving federal funding.

IFAI — the Indigenous Food and Ag Initiative — and FRAC and NAAF came together to provide the data that will help educate Congress when they’re making decisions about food implementation and agricultural production across the country, in particular Indian Country.

HCN: Why is self-sufficiency so much more effective?

TS-M: Because they intimately know their neighbors. They know culturally how their communities function. And they know how to get to their membership in the best possible manner. So, in one community, it might be working through mobile slaughter [units]. In another community, it might be distribution of food boxes. In another community that’s not so far removed from a town or city, it might be working with food banks. And so those community members, the tribal governing authority — they know that better than an outside entity, better than a state entity.

A lot of our tribes have economic arms of their tribal government that have some type of food- or agricultural-based business. They utilize those businesses to get that food to their community members. And that’s the model we want to see. Those producers within those communities can sell their food locally. It reduces transportation and storage costs, it reduces or works toward eliminating issues that you would see in long transportation. In the end, they will save money, because these communities will have additional dollars, so the value of their dollar will remain stronger, won’t be chipped away by having to go through multiple states or processing plants or transportation companies. And, again, if we have natural disasters, we have a pandemic, then the communities can stand up and serve their citizens, as opposed to waiting for Washington, D.C., or even the state capital to try to get to them.

If you look at Eastern Washington, the Yakama Nation and the Colville Confederated Tribes, collectively, we have close to 10 million acres. The export industry in cherries and apples alone is in the billions — and yet our tribes are not billionaires. So there’s an opportunity there to pivot and diversify away from, say, gaming, and work towards making agriculture not only a food-security issue, but an economic development opportunity.

HCN: Are you optimistic that Congress is going to take this data into account and begin to more deeply or meaningfully empower tribal communities to support themselves through their own agricultural infrastructure?

TS-M: We hope so. Our overall vision document is, through this regional agricultural infrastructure, about standing up everything that these communities or regions will need in order to feed themselves. That’s grain elevators, it’s rail transportation, it’s kitchens and processing plants. But it’s also marketing, packaging and distribution. And so having access to all of those in a regionalized manner will unburden the individual tribe or individual farmer or producer from having to stand up that infrastructure themselves. It would all be done in a regenerative, climate smart manner. And, again, reducing the amount of transportation, all of those things moving towards helping the environment and helping these rural tribal communities at the same time. We’re asking tribes to reach out and engage with us if they’re applying for federal funding, to use our work as a model of how we can all come together and actually leverage private and federal funding and expand and unify our mission, which is to feed our communities, but do so in a manner that supports those community members and not necessarily a corporation.

This is just the beginning. We’re going to continue to do more data-related research. For the first time, we’re going to take ownership of our data, and also the messaging and how that data is going to be interpreted. A lot of this generation has benefited from the work of our ancestors. And we’re in a place where a lot of tribal communities are working toward large scale, either cultural development, gaming, you name it, government contracting. These tribes are moving into spaces they’ve never been before. Tthey’re able to support their communities better. We have higher rates of participation in higher education and vocational education. And we want to continue that upward trajectory and supply the celebration of our traditional ecological knowledge. So this is just an opportunity. And it’s our first step going after and providing this type of data.

And we’re not just working with tribal entities; we’re working across the spectrum. We’re working with other large-scale agricultural industry groups, and nonprofits and federal agencies. And our hope is that we can do some focus work, to stand up agricultural infrastructure in rural communities and show the world that it can work and that these communities can have ownership over their food and food security.

This story was originally published at High Country News on Feb. 11, 2022.