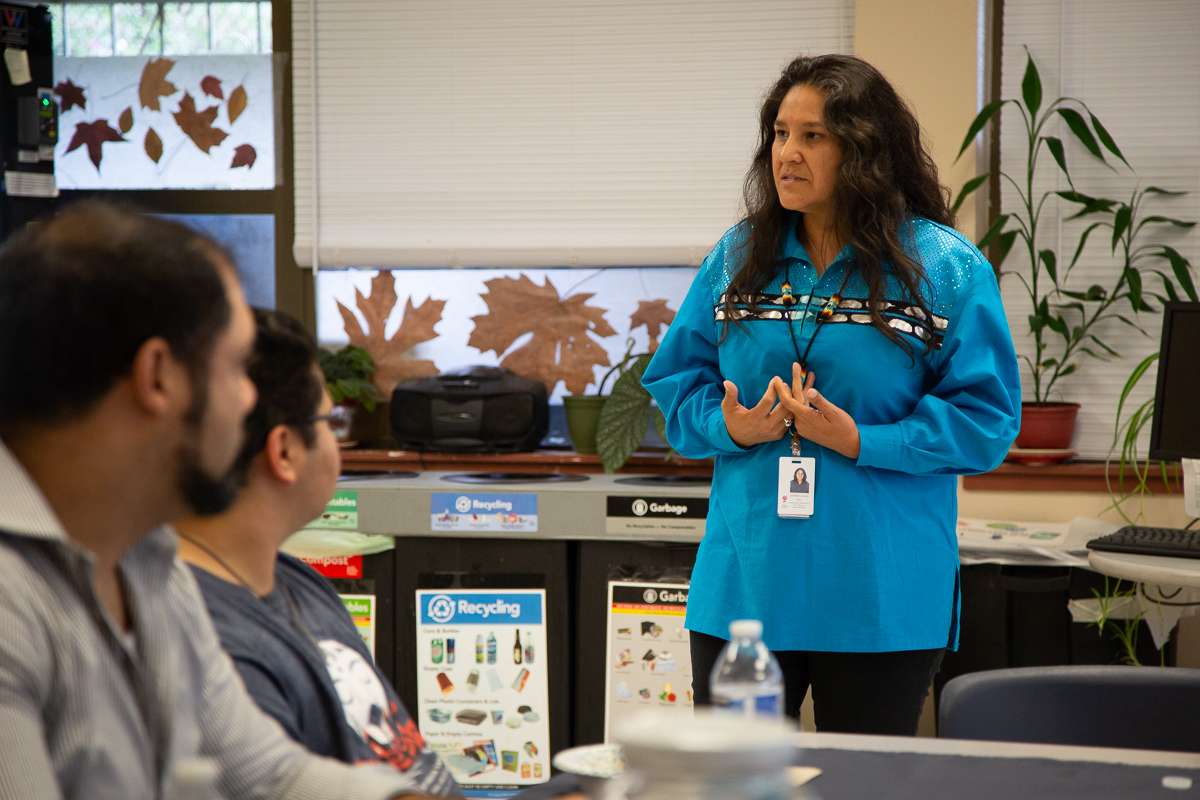

At the night’s event, members of Seattle’s indigenous community were given a space to share a meal, tell their stories and, with the help of SIHB employees, input data into the Department of Justice’s public NamUs database. Some, like Lucero, shared their reflections.

As Lucero spoke, she glanced at Abigail Echo-Hawk, SIHB’s chief research officer and one of the lead organizers of the gathering. “Abigail’s going to learn something about me. She learns something about me every time we do something like this.”

“One of the things that I actually have never shared with anybody is that my auntie is a murdered indigenous woman — she was murdered by her partner, who was never held accountable,” Lucero says. She says her aunt was a queer woman, and her then-partner was never brought to justice. When Lucero came out as queer, she said it took her mother time to accept that she wouldn’t inevitably meet that end, too.

“That’s a burden that my mom carries,” Lucero says.

Of the 5,700 reports of missing indigenous women nationwide, only 116 are recorded in the Department of Justice’s Missing and Unidentified Persons System (NamUs), according to the Urban Indian Health Institute’s groundbreaking report from last November. The report goes on to blame this discrepancy in part on an inadequate response in data collection from law enforcement. This gap in information between what Native people experience and what’s represented in federal and state databases has helped advocates form the term “data sovereignty:” essentially, a movement where Natives themselves own the ways in which information about their communities is gathered and disseminated.

Lucero’s experience is shared by many who have sought government accountability for showcasing data that doesn’t reflect the scope of the tragedies they’ve lived with. It’s the basis of the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women’s movement, which demands government accountability for the data gap and better reporting methods.

The movement received a boost in national mainstream recognition last year after Echo-Hawk made public a report about the extraordinarily high rate of sexual violence against indigenous women in Seattle. Echo-Hawk hopes that through their data gathering, Native communities can act on their reports in ways that law enforcement has not.

“We thought, ‘Let’s switch it. Let’s put the power back in the hands of the community,’ ” she says. “Law enforcement isn’t entering in the data so instead, let’s do it ourselves as a means to take action, call for accountability and flip the script.”

The gathering at SIHB’s headquarters last Thursday night was the first of many events Echo-Hawk hopes to see among Native communities across the country. She says it’s one way to actively fill that data gap, bring attention to their crisis and perhaps bring closure to affected families.

“Is it fair to place the responsibility to enter in the data to the families? It’s not. It’s an unfair burden, but we also recognize law enforcement isn’t doing it,” she says. “So at this point, we have to do it. It shouldn’t be that way.”

‘We’re literally invisible — we’re dying in vain’

Many researchers and advocates working to better represent Native populations through data point to the government’s historically spotty methods as a root cause of today’s problem. For researcher and co-founder of the U.S. Data Sovereignty Network Desi Rodriguez-Lonebear, that problem starts more than a century ago: Throughout the first several censuses in U.S. history, Native people in the United States who weren’t taxed weren’t even counted as existing. While the census began in 1790, many Native people weren’t counted until 1860.

Even after Native people were added to the census, undercounts persisted. It remains a concern for the National Congress of American Indians for the 2020 census: American Indians and Alaska Natives living on reservations were undercounted by 4.9% in the last census, according to U.S. Census Bureau estimates. While there are many possible explanations for this (the Census Bureau includes poverty and linguistic isolation as contributing factors), Rodriguez-Lonebear says that undercounts are exacerbated by the lack of diversity in racial categories present in the census, leading to misclassification.

“Tribes aren’t even in the mix,” she says. “We’re not racial groups; we’re not ethnic groups. We’re sovereign nations.”

This also happens when a Native person dies. A 2016 report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that American Indians and Alaska Natives are often misclassified as white. All this, Rodriguez-Lonebear says, erases the population of Native people in the United States. This matters tremendously when it comes to allocation of resources: Funding, aid and attention at the federal level in everything from health services to justice derive from census numbers.

“We’re still trying to get people to acknowledge that we even exist,” Rodriguez-Lonebear says. “We’re literally invisible — we’re dying in vain.”

Gabe Galanda, an attorney in Seattle representing tribal governments, says that another factor in undercounting is disenrollment, which is when a Native person’s tribal citizenship is rescinded (the Nooksack Tribe in northern Washington just disenrolled some 300 tribe members amid controversy).

“Disenrollment is another way in which tribal peoples vanish from [the] indigenous community and tribal society,” Galanda says. “Tribes are funded by the number of members they have.” And when those numbers look small, he says, that lack of funds can make their communities shrink even further.

‘By us, for us’

In recent years, governments have attempted to fix these issues by better involving Native communities in their data gathering. The Washington State Patrol released a report last June after a year of gathering information about missing and murdered indigenous women by visiting tribal communities around the state. The outreach largely focused on understanding why inadequate data existed, concluding that the effort helped them better understand the Native community’s needs and difficulty in reporting cases. Washington State Patrol Capt. Monica Alexander, who attended each gathering, says it also influenced House Bill 1317, a proposal to recruit two tribal liaisons to work on cases of missing Native people. The bill was passed last April. Alexander acknowledges her role was a temporary fix, and she hopes the bill keeps the state from losing momentum on the issue.

“I was kind of a placeholder,” Alexander says. “But the liaisons are hopefully going to be able to really dig into the [issue.]”

While there are some publicly available databases, like NamUs, where missing or murdered loved ones can be reported, the state patrol’s report concedes that they didn’t adequately serve the concerns heard in these community gatherings. It stated: “There currently is no centralized database that is all-encompassing of the information necessary to effectively meet the needs of this growing problem.”

Although such a database might not exist within federal or state governments, Native people like Annita Lucchesi have taken it upon themselves to make one. Lucchesi founded the Sovereign Bodies Institute, which currently has over 4,000 reports of missing and murdered indigenous women within its database. Lucchesi says she’s certain there are thousands more to come. With this database, she was determined to give Native people ownership over this information. As a rule, she says, “We don’t provide data to colonial governments, and we don’t take money from colonial governments.”

“There’s all this research being done but it’s not being done by us,” she says. “I thought: What if we do things differently? What if we do research that’s by us, for us?”

Lucchesi was unsatisfied with the Washington State Patrol’s report, explaining that she doesn’t think it was the right department to conduct it. After all, she says that it’s law enforcement that hasn’t adequately responded to their reports in the past.

“They’re partially responsible in the first place with missing persons cases,” she says.

Her institute’s database, she adds, is only possible because of the personal relationships and understandings she’s maintained with the people who volunteer information.

“I really stress to them, ‘This is something that belongs to you,’ ” Lucchesi says. “‘So what should it be?’”

The SIHB plans to hold data-gathering events soon. In the meantime, they’re encouraging others to hold gatherings as well: Echo-Hawk says they’ve already heard from individuals and organizations in Arizona and Montana that plan to hold similar data-gathering events this year. She hopes that these gatherings can provide support for community members who’ve long stayed silent about their lost and murdered family members and friends.

Echo-Hawk says it’s also a call for accountability from law enforcement, which she hopes will improve its methods of information gathering nationwide.

“If I can get people to come enter in data, if I can have communities across the country doing it, why can’t they do it?” she says. “It really does point to avenues where there’s been inaction by law enforcement, where there’s an opportunity for them to make good positive change because our communities shouldn’t have to do this.”