My successor at the Herald, Annette Cary, who is the most knowledgeable reporter today on Hanford, also worked the beat for years before she felt comfortable that she understood the site.

When I moved to Seattle in 2009, I found that many people on this side of the Cascade Range had never heard of Hanford. Most of the rest were vaguely aware that a spot in Eastern Washington was radioactive in some way or another. Only a small percentage of Western Washington residents knew Hanford created plutonium for two atomic bombs during World War II and for the bulk of U.S. atomic bombs ever since.

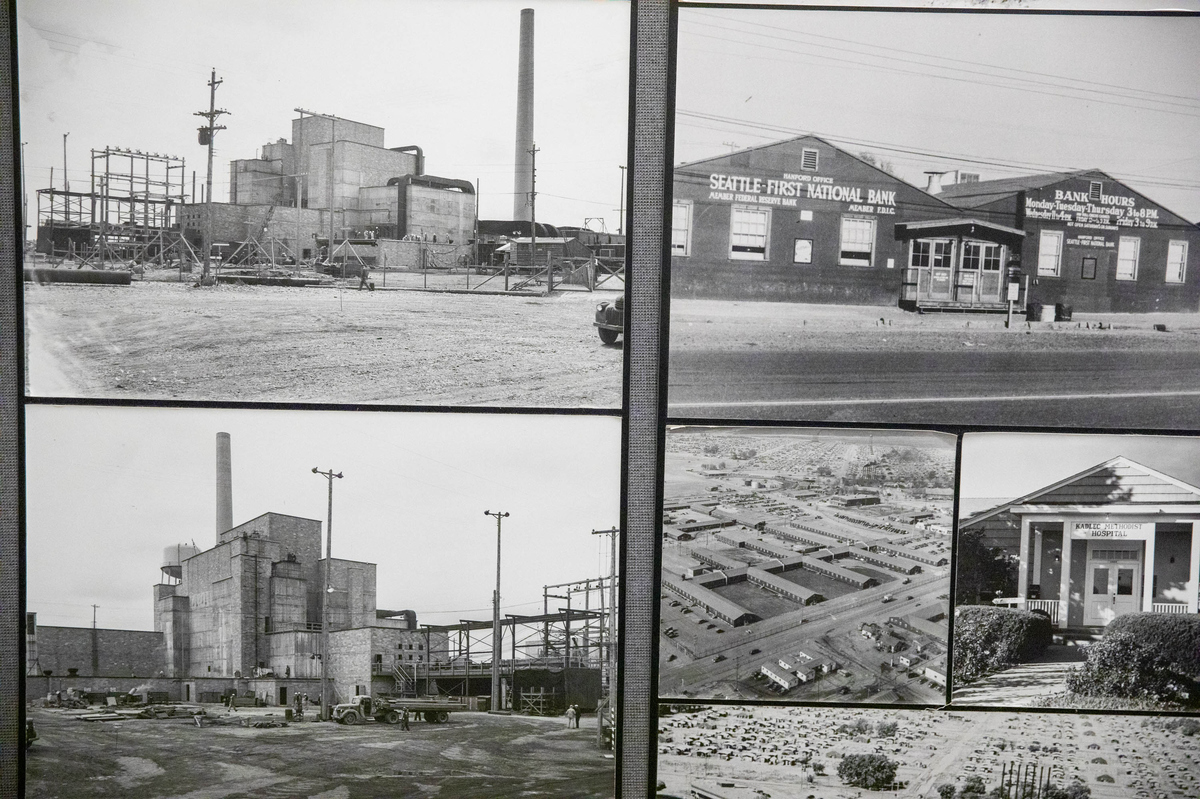

Today, Hanford is the most radioactively and chemically contaminated spot in the Western Hemisphere. It’s roughly 200 miles from Seattle. And it's out of mind for most King County residents.

Hanford is one of the most complicated journalism beats in the Northwest. Massively intimidating. I knew several reporters who avoided covering the site because it is hard to understand. In the past 30 years, maybe 10 reporters scattered across Washington and Oregon really poked into Hanford’s nooks and crannies. More than half are now retired, left journalism or gone elsewhere.

I’m one of the few remaining. I wrote my first Hanford story in 1991. I started seriously reporting on it in 1993.

The subject is fascinating as hell. The few of us who have covered it became intrigued by the complexity and stakes.

Parts of Hanford will be radioactive for thousands of years. The worst waste is seven miles from the Columbia River – the river that carries salmon to be eaten by orcas swimming in the Pacific Ocean. Roughly 180 square miles of contaminated groundwater lies beneath the 580-square-mile site, polluted by 400 billion gallons of chemical contaminants poured directly into the ground. Hanford has 56 million gallons of highly radioactive wastes stored in 177 underground tanks with roughly a third leaking.

When I covered the site full-time in the 1990s and early 2000s, roughly 40 different public interests debated and fought over approximately 50 separate environmental and economic issues.

It was exciting for a journalist to cover. And still is.

There was a big chemical explosion in 1997. The site’s internal and external politics could get nasty. Heads sometimes rolled. Blue-collar workers intermingled with engineers and scientists. Several times, I wandered around highly radioactive areas wearing funky protective gear. The interiors of huge plutonium processing buildings looked like sets from the first couple Terminator movies. I wandered the site of today’s $17 billion partly built waste-glassification complex when it was nothing but sagebrush. From the 1940s to the 1960s, a few human experiments took place that would not pass today’s safety protocols. At one point, a massive range fire threatened barrels of radioactive uranium chips stored in oil.

Some matters were more fun to write about.

Radioactive tumbleweeds bounced around. Some workers had to combat radioactive ants (see 1954’s B-movie monster ant classic Them.) Scientists experimented on alligators in the 1960s and a couple escaped; one was never found again. I was caught in the middle of a stampede of several hundred elk in a Hanford buffer zone. Research projects into cutting-edge physics were stashed here and there on the site. Hanford was the crossroads of the pre-settler migratory paths of several Northwest tribes. I went through SWAT training with the site’s security force.

In fairness to Hanford, about 95 percent of its employees have been hard-working and conscientious. Many projects involving plutonium processing, water-filled pools of used nuclear fuel and cleanup of groundwater have succeeded. But much of my job was to tell the public about the screwups and the things that did not work.

I kept covering Hanford off and on for various news organizations after I left the Tri-Cities. It is a topic I cannot resist writing about. It would not be an exaggeration to say I am addicted to the beat. Recently I even offered to write a story for free because my editor expressed no enthusiasm for the idea. She scolded me for offering to write for free, and then said I could write the story.

One of the things that got drilled into me in a 40-year career in journalism is our watchdog function. That concept has always spoken to me.

Twenty to 30 years ago, several Northwest newspapers plus The Associated Press tripped over each other unearthing news at Hanford. Today, Hanford coverage is scarce and sporadic. Which is a shame.

That’s why I still write Hanford stories for Crosscut.

Get more Crosscut in your inbox

Sign up for our Daily newsletter for the most important headlines of the day or sign up for our Weekly newsletter for the best stories of the week. Or, select both for more Crosscut.