Built in 1943 and 1944 and shut down since 1968, the Manhattan Project B Reactor is now a tourist attraction in Eastern Washington on the site where plutonium was processed for the atomic bombs exploded in 1945 at the Trinity site in New Mexico and at Nagasaki, sparking the end of World War II.

The U.S. Department of Energy and the National Parks Service offer public tours of the world’s first industrial-sized nuclear reactor, beginning with a 25-mile bus ride from northwest Richland into the nuclear site.

The B Reactor is actually one of three tourist attractions associated with the Hanford site. The second, the LIGO Exploration Center, opened in September and invites science enthusiasts of all ages to dive into astrophysics. And the National Park Service covers the history of the Manhattan Project and Hanford at a visitors’ center in Richland.

On a recent Wednesday, 46 people from as far away as New England toured the B Reactor. “It’s an amazing site. We’re glad we came,” said Ravi Joshi of Dartmouth, Massachusetts. He and his wife, Laura, were visiting Richland to see their daughter Leena, a Hanford health physics technician.

The B Reactor attracted roughly 3,000 visitors when it opened for public tours in 2009. Tourists numbered 14,537 in 2019 before the reactor was closed during the pandemic. Tours slowly ramped back up this year to tally 4,551 visitors by mid-October.

“This little place in southeast Washington changed history and started the Atomic Age. … It did what it was supposed to do and did it against all odds,” said Colleen French, the U.S. Department of Energy official who guided the B Reactor to become a national park.

Free daily tours begin at 8:30 a.m. at the national park’s headquarters in the middle of a mini-strip mall in northwestern Richland, located along two-lane State Route 240 stretching into the Hanford nuclear reservation. The required bus ride takes visitors 45 minutes through the quasi-desert to the B Reactor.

During the trip, tour guide Terry Andre talked about creating the B Reactor; Albert Einstein warning FDR about nuclear fission; American fears about Germany developing an atomic bomb first; and why Hanford and the B Reactor were built where they are in Eastern Washington.

The U.S. government chose the location — three Eastern Washington farm villages, Hanford, Richland and White Bluffs — because they were isolated and next to the Columbia River to provide needed water for the reactor. The story includes a lot of drama, including the reality that local people had to be displaced to make room for a secret plutonium factory, which had never been attempted before.

DuPont de Nemours Inc. agreed to design and build the B Reactor to create plutonium from uranium fuel rods, plus a battleship-sized indoor chemical plant — T Plant — to extract the plutonium sprinkles from the irradiated fuel rods.

The cost to the feds: $1.

That was because DuPont picked up a nickname that it hated for making massive amounts of money providing munitions in World War I. “It would be a great name for a punk-rock band, but not for a business: ‘The Merchants of Death,’” Andre said. DuPont insisted on the $1 fee to show its non-exploitative patriotic involvement in World War II.

More than 100,000 people were hired to work at the site, but a huge percentage soon left. Hanford was in the middle of nowhere, with no development for 50 to 70 miles in any direction. The climate is really hot or really cold, punctuated by dust storms. The government provided primitive, barrack-style living conditions. Only a handful at the top knew the big picture; most of the workers did not know plutonium was being created.

Andre also told the bus riders about Leona Woods, an Illinois farm girl who earned a Ph.D. in physics in 1942 at age 23, becoming the only woman and youngest physicist in the Manhattan Project. She overcame sexism to work on the first small experimental plutonium-making reactor in Chicago with her mentor Enrico Fermi. Woods moved to Hanford to help develop the B Reactor in 1943. She got married, got pregnant and hid her pregnancy beneath baggy work clothes so she wasn’t banned from the reactor. And Woods was one of the few who knew the project’s big picture.

Just short of reaching the Columbia River, the tour bus turned right off State Route 240. A weather-beaten gate opened, and then about a minute later visitors could see the B Reactor building, a tall gray concrete cube with a smokestack. A railroad track with a defunct-looking locomotive sits next to it among the scrubby desert dirt and dust.

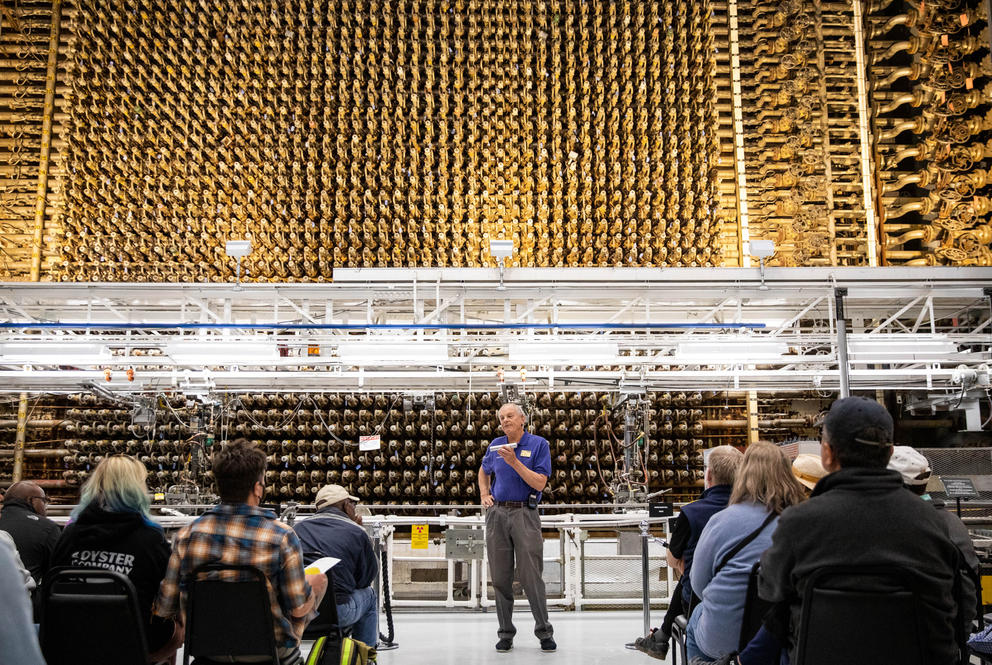

Visitors enter the building into a cavernous chamber. At one end looms the B Reactor’s core: 36 feet tall, stretching across 28 feet of floor, with 2,004 horizontal tubes with their ends facing the tourists. “I didn’t think it would be as big as it was. It was cool,” said Jessica Barker of Elkins, North Carolina.

The reactor core gives off a steampunk ambience, Jules Verne on steroids.

Standing in front of the core, a second tour guide, Rick Bond, explained how the reactor core worked. When bombarded with neutrons, the uranium 238 isotopes within the 2,004 fuel rods created uranium 239 isotopes, which then became neptunium 239, which then became specks of plutonium 239 within the fuel rods.

A sense of urgency flooded World War II-era Hanford.

“Germany was working on a bomb. We had to beat them to the punch,” Bond said. It was not until after the war that the Allies learned that the Germans were still blundering around with their initial experiments when they surrendered in 1945.

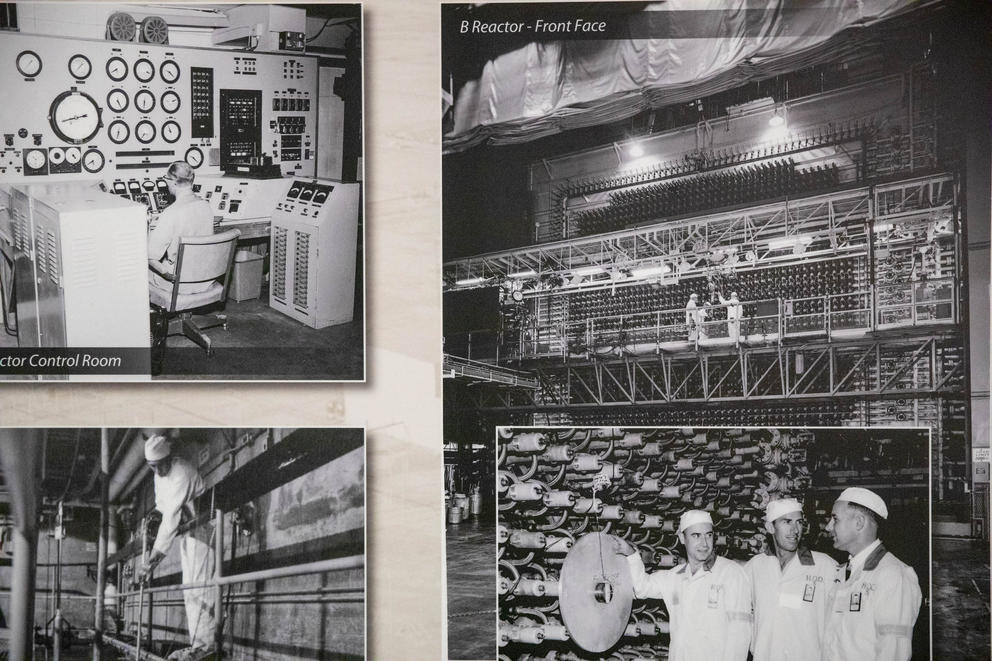

After looking at the reactor core, tourists checked out several outlying rooms, including the main control room.

Camped out in the control room, Andre returned to Leona Woods’ story and the tensest day in B Reactor’s history — Sept. 26, 1944.

That day, the reactor cranked up to using roughly 1,500 fuel rods, then sputtered down, then up and then down again. Andre mimicked Woods’ cultured voice in an oral-history recording: “It was dead. It just went dead.”

Fermi, Woods and others whipped out their slide rules and pondered and calculated. They quickly figured out that the nuclear reactions created an isotope called xenon 135, which captured neutrons intended to go elsewhere during the process.”Think of the Cookie Monster … It was the Cookie Monster of neutrons,” Andre said.

They figured out that more fuel rods than 1,500 would be needed to fix the problem. Luckily, DuPont had made room for 2,004 fuel rods as a hedge against possible miscalculations. The xenon problem was quickly fixed.

By mid-1945, Hanford had processed enough plutonium for a handful of atomic bombs. “It’s mind-boggling how they did it that fast,” said tourist Bernie Charvet of Grandview, Washington. Since the Hanford assignment was completed ahead of schedule, the feds paid DuPont only 68 cents. A Pasco Kiwanis club contributed 32 pennies to ensure DuPont received its full dollar.

Hanford’s plutonium was used inside the first atomic blast at the Trinity site in New Mexico on July 16, 1945. While Hanford produced plutonium, a parallel effort in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, created uranium to use in a bullet-like bomb that destroyed Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, killing 70,000 to 80,000 people. A B-29 bomber dropped a plutonium bomb on Nagasaki on Aug. 9, killing between 39,000 and 80,000 people. World War II ended less than a week later.

Richland embraced its role in ending World War II. The local high school sports teams became the “Bombers,” with joint logos of a mushroom cloud or a B-17 bomber. Local histories are hazy on which logo came first. During World War II, Hanford’s workers all contributed one day’s pay to build a B-17.

Eventually, nine plutonium-production reactors and several plutonium processing plants were built at Hanford during the Cold War to build up the United States’ nuclear arsenal. The chemical and radioactive wastes from those processes were either dumped directly into the ground or into 177 underground tanks, leading Hanford to become the most contaminated chunk of land in the Western Hemisphere.

The Tri-Cities’ pride in birthing the Atomic Age led to Democratic U.S. Sen. Maria Cantwell and former Republican U.S. Rep. Richard “Doc” Hastings asking Congress in 2004 to make the B Reactor, T Plant and remnants of the displaced farm villages into a national park. Oak Ridge and Los Alamos, New Mexico — where the bombs were assembled — also wanted national park designations.

At first, only Los Alamos received that honor. But the communities banded together to ensure all three did. It took until 2014 for congressional members to shepherd the joint designations and the money to fund the sites. The deaths and devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki spurred opposition to the idea in Congress.

French said the focus of the B Reactor national park site is on science and engineering, but Nagasaki’s devastation and the 1942 displacement of local residents might be addressed in the future.