Juris needs to ensure he uses the right amount of fertilizer. Too much can damage the plant, but not enough may prevent full development.

But Juris says the proper use of fertilizers also ensures optimal use of water, which can be more limited in drought years.

Last week, the Washington Department of Ecology declared a drought emergency for most of the state, aiming to help everyone from farmers to local irrigation districts better prepare for drought in the coming months.

This nearly statewide drought emergency is the third in the past decade — a similar emergency was declared in 2015 and 2021. Even in years without a statewide declaration, Ecology has declared drought emergencies for portions of the state, such as the one declared last year for 12 counties, including Yakima, Benton, Walla Walla and Kittitas, counties with robust agriculture industries.

Climate change has made extreme weather events, such as the heat dome from 2021, more frequent.

For growers like Juris and others in the agriculture industry, it’s not just about enduring drought conditions for this season alone, but changing in response to anticipated drought in the years and decades to come.

Agriculture industry officials are evaluating every aspect of the production process to help their crops be more resilient to future drought.

“On our farm, I get the crop the best I can in a position of health,” Juris said. “Wheat plants are like people. When [plants are healthy], you can handle stress.”

Drought conditions

The state Department of Ecology declared a drought emergency on April 16. The agency stated that it declared the emergency to allow those affected to be better prepared. The declaration also provides access to grants and other programs that can help mitigate the issue.

For 12 counties in the state, the declaration extended last year’s emergency. Last year’s conditions already caused a deficit in precipitation needed for sufficient snowpack, said Caroline Mellor, statewide drought lead for Ecology.

When the emergency was declared, the snowpack was at 68% statewide, with several areas reporting even significantly lower numbers.

With forecasts of a warm and sunny spring, officials anticipate that snow will melt too fast, leaving areas without needed water, Mellor said.

For agriculture, crucial water supply may drop when growers need it most in the summer and fall when harvest starts for many of the state’s agricultural commodities.

Drought during tough years for agriculture

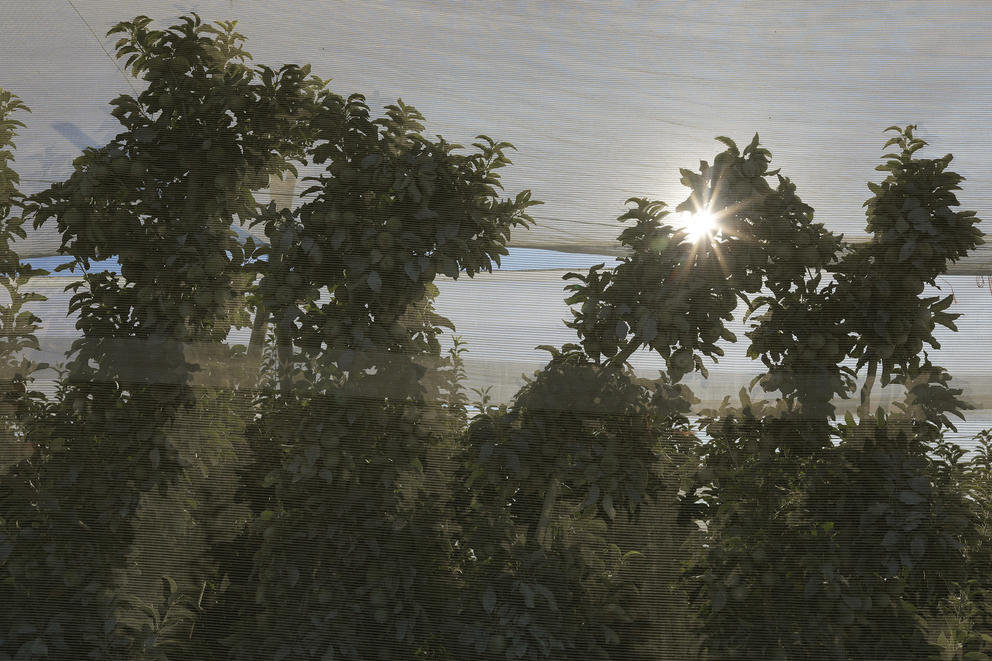

Anticipated drought conditions come as growers of tree fruit, including apples and cherries, are still recovering from losses from both abnormally cold and warm temperatures in past years.

Apples are the state’s top crop, with a valuation of $2.07 billion in 2022, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Cherries are also among the state’s top 10 crops, at $407 million.

In 2022, a cold and snowy spring stunted the development of apples and cherries, leading to the lowest crop volumes in over a decade.

Then, last year, cherry growers were hit with the opposite issue — abnormally warm spring temperatures. This led to a condensed harvest that caused an oversaturation of the market, lowering prices. That prompted U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack to issue a formal disaster declaration to allow Washington cherry growers to get federal emergency loans to help recover losses.

Drought comes as Washington tree-fruit growers — primarily in the Yakima Valley, Wenatchee Valley and Columbia Basin in Central Washington — are seeing declining returns and increasing costs, said Jon DeVaney, president of the Washington State Tree Fruit Association. “That’s an added headache no one needed.”

But this year’s early declaration of drought does allow the industry to prepare, DeVaney said. Local irrigation districts are already prepared to work together to make water available to growers. So an irrigation district that has extra water may transfer it to another district where there’s more need from growers. However, growers will have to pay for the transfer.

Meanwhile, wheat growers in Eastern Washington are still recovering from the drought and extreme heat of 2021, which sapped moisture from the soil and, with minimal precipitation, caused a drastic drop in yields. That year, Washington growers produced 87.1 million bushels of wheat, well below normal levels of 145 to 160 million bushels, said Michelle Hennings, executive director of the Washington Association of Wheat Growers. A bushel of wheat is about 60 pounds.

That kind of decrease in harvests could leave a huge financial hit. The USDA values Washington’s wheat at $1.17 billion, making it among the state’s top three agricultural commodities, just behind apples and milk. About 90% of the state’s wheat is exported, and in 2022, it was among the top three exported agricultural commodities at $894 million. If Washington can’t supply wheat due to reduced yields, many other countries are ready to step in.

Most growers relied on crop insurance to help recover the losses of 2021 and rebuild. Growers saw things bounce back in 2022, when the crop reached 144 million bushels. Numbers dropped again in 2023, to 113 million bushels, but that was still an improvement over 2021.

Now, growers are already feeling the effects of drought. Many growers this spring had to reseed their fields because the seeds planted last fall didn’t develop due to a lack of moisture, Hennings said.

Hennings said it made sense for Ecology to declare an emergency now rather than wait until the impact hit growers. “We’ve been through it before,” she said. “It’s nice when they have these emergency drought programs.”

Such times test a grower’s entire operation, says Juris, the dryland wheat grower in Bickleton. Growers now have to balance skyrocketing costs with declining returns from the export market. They must also learn to utilize technology and analyze data to ensure that raw materials are used to their maximum value.

“Everyone pictures a farmer with a straw hat and pitchfork,” Juris said. “Anymore, you have to be a CFO, a CEO, an accountant, and a chemist.”

Thinking ahead

With so many drought emergencies in recent years, industry experts said growers need to adopt practices to better prepare for future drought.

The industry is working alongside researchers at Washington State University on efforts that may lead to long-term solutions.

Sonia Hall, a research associate at the Center for Sustaining Agriculture and Natural Resources at WSU, is part of a team investigating how changing climate conditions have shifted the availability of water in Eastern Washington and what that means for agricultural producers, especially those who may see their water supply curtailed or shut off due to drought.

Even in non-drought years, this information is important because a sufficient supply of water may come when growers’ demand is lower, Hall said. Understanding that timing is crucial to helping all involved — from policymakers to agricultural producers — get a sense of what’s to come and make the key long-term investments to respond to the changing water availability.

She said the conversation around drought in a given year isn’t just about how to get relief that year, but also about what information it provides on what needs to be done in the long term by both growers and policymakers.

DeVaney, the Washington State Tree Fruit Association president, noted growing interest in research on climate models. With climate change leading to more frequent adverse weather events, climate models must be adjusted to help growers better anticipate such events, including ones that lead to drought, and the practices they should adopt.

WSU also conducts research on apple varieties that may grow better under drought conditions or temperature fluctuations.

“Growers have been seeing a lot of these kinds of weather events that’s causing financial challenges for them,” DeVaney said. “What kind of management practices will be appropriate for that environment?”

Hennings said the Washington wheat industry is also working with WSU to research more drought-resilient varieties.

Juris agrees that more needs to be done with climate models, noting that drought occurred during years for which the old long-term forecast models had predicted more precipitation.

“Those 50-year averages don’t seem to hold anymore,” he said.