That’s one of the major takeaways from the most extensive study to date of heat-related mortality risk in Washington, which revealed that people everywhere are at greater risk of dying on the days that feel hottest to them. That risk, researchers found, will continue to increase as the climate warms.

In their study, published in the journal Atmosphere on Aug. 30, University of Washington researchers analyzed the risk of heat-related death across the state. They analyzed state Department of Health data to discover that between 1980 and 2018, people everywhere were more likely to die as days felt hotter, and that sex, health status and race (due to socioeconomic but not biological factors) affected risk.

At the state level, the Department of Health’s Washington Tracking Network attributes 38 deaths to heat stress between 2016 and 2020, the most recently available reporting period.

The research is intended to inform public health professionals as they strategize to keep their communities safe through things like heat-safety alert messages and climate mitigation efforts. They also forecast increasing risk in 2030, 2050 and 2080.

It can be hard to compare how heat impacts communities because temperature isn’t the only thing that influences how hot a day feels. Researchers use a standard called a “humidex,” or humidity index, to try to account for this. This index considers the impact of relative humidity in addition to temperature, producing a humidex value expressed as a number. Higher numbers indicate increasingly uncomfortable conditions.

“The idea is that a 75-degree day can feel amazing if there is no humidity but may feel very muggy and unpleasant if humidity is high, and this difference can have an important influence on an individual's physiological response,” said lead author Logan Arnold, whose Master’s thesis research culminated in this study.

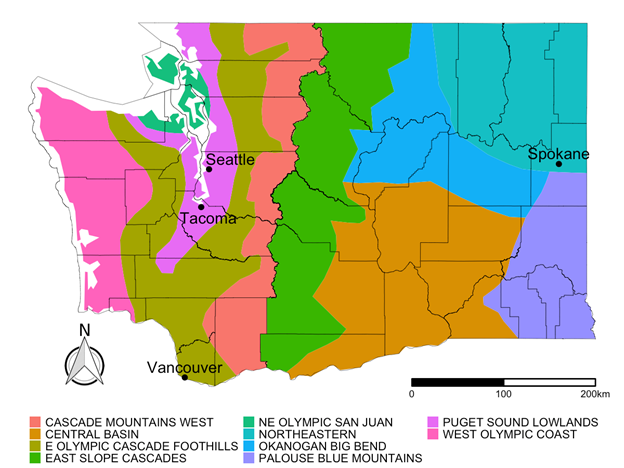

After breaking up the state into 10 federally designated climate regions and pairing death data with humidex data, the researchers found something striking: People were 8% more likely to die on days in the 99th percentile of humidex in their location, or the absolute hottest-feeling days, compared to average-feeling days.

“Risk is not uniformly experienced — place matters,” study co-author Dr. Tania Busch Isaksen, an associate teaching professor in UW’s Department of Occupational and Environmental Health Sciences, wrote in an email.

A map of Washington's 10 climate regions. University of Washington researchers evaluated mortality data in these regions, designated by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and were able to show statistically that heat had a measurable and significant impact on death in at least four regions: the Puget Sound lowlands; the east slope Cascades; the Northeast Olympic San Juan region; and the Northeastern region. (Courtesy of Logan Arnold.)

People acclimate to the weather they experience in their daily lives, so the same combination of temperature and humidity can feel different to someone depending on where they live. That’s one reason people in much of temperate Washington may struggle more than, say, people in Arizona would in the same amount of temperature and humidity, and why even small increases in heat can have sizeable impacts on our health.

The majority of data comes from the Puget Sound region, home to most people in the state.

“An 8% increase in preventable mortality is quite a big deal,” says Busch Isaksen, who advised Arnold in his research.

Researchers homed in on a humidex of 30 — between 71 degrees Fahrenheit in high relative humidity and 84ºF in low humidity, according to Arnold — as the point at which Washingtonians’ risk of death started to increase. That’s a lower humidex than what would trigger health alerts in many other parts of the country.

The researchers had enough data in four of the state’s 10 climate regions, including those home to Seattle, Bellingham and Tacoma, to be certain that their populations were statistically more likely to die on each region’s hottest days.

It’s experience-confirming proof for public health practitioners and residents who’ve braced heat domes without air conditioning, and a wakeup call for some municipalities.

“This study validates the fact that many factors influence the effect of heat on a person,” Public Health Seattle-King County’s Kate Cole said via email.

Digging into the data

Busch Isaksen, who has been at the vanguard of heat-stress and smoke-health-impact research in Washington state, had long wanted to attempt a study of heat-related mortality and climate zones. Arnold, one of her students, agreed to pursue it. The researchers believed looking at mortality by climate region rather than by ZIP code or county could more usefully describe people’s relative risk.

Counties can span multiple climates, so their residents may be acclimated to different amounts of heat; and since fewer people live in rural municipalities, rural areas don’t always produce enough death data to prove anything beyond chance alone. Including these less-populous areas in larger similar-climate regions makes it possible to account for them.

The climate-region approach resonated with Rad Cunningham, a climate-focused senior epidemiologist at the state Department of Health, who hadn’t seen this method of blending climatology and health data before.

“When I saw that in the paper, I was like, obviously, this is how we [should] do it,” he said. “I think [this] will likely be one of the key pieces of research we use for characterizing health risks for a while.”

To figure out local mortality risk, the researchers paired geocoded data with the local temperature on the date a person died and other relevant dates. Data was first available in 1980, but reporting lags limited researchers to data from 2018 and prior. That means the analysis doesn’t even include the past few years’ heat crises, like the 2021 heat dome in Puget Sound.

The researchers are more certain of results in some climate regions than in others, owing to the quantity of data available for each area, which complicates their ability to compare risk among regions. But by using the best data available, the UW report provides the most detailed understanding of statewide heat-related mortality risk to date.

The researchers had enough data to prove that heat, not just chance, played a role in increased risk of death in the Puget Sound Lowlands, Northeastern, East Slope Cascades and Northeast Olympic San Juans climate regions. In these regions, the mortality rate also appears to rise faster as heat increases than in other regions of the state. However, researchers say this doesn’t necessarily mean that people in other regions don’t experience just as much heat risk.

“Our results were only statistically significant in [those] four of the 10 regions we evaluated, indicating that the steps that we took were likely not enough to eliminate sample-size issues in rural areas of the state,” Arnold said.

Even so, Dr. Mark Scheuerell, study co-author and an associate professor in the School of Aquatic Fishery Sciences at UW, felt comfortable saying people in these areas may be more vulnerable to humidex increases than those elsewhere, based on data so far, for reasons that are still being teased out.

“I think those are reasonable takeaways, and we need more data,” Cunningham added. “It's not that the Puget Sound Lowlands and the other [three] regions are the hottest, but it's likely that they're the least adapted to heat.” Adapting to the changes, he said, could meaningfully decrease that risk.

In high heat, some people consistently pay the price

Common and regrettable patterns of inequality exist within the state’s death data, with people in certain demographics more vulnerable to dying than others. Women were more likely to die on the hottest days than men, and Black people were more likely to die than their white neighbors. People with underlying health conditions like diabetes were also more vulnerable because they can have a tougher time regulating their body temperature due to the condition itself or medication taken to manage it.

Researchers had to do some statistical detective work to surface the elevated risk from underlying disease. Heat-related deaths in people with underlying health conditions are often attributed to those conditions rather than to heat stroke, dehydration or heat illness exacerbated by them.

“This study tells us that the health impacts of heat are much wider-reaching than the hyperthermia deaths we hear about immediately following hot days. While any heat-related death is one too many, this study validates the fact that the death toll from higher temperatures is higher and harder to detect than initial reporting typically captures,” said Cole.

Heat-related deaths aren’t inevitable

Previous heat-related mortality risk research has focused on areas with large populations and urban centers, like King County, which has consequently been better informed as it improves its heat strategy.

The county recently incorporated the National Weather Service’s HeatRisk index, a prototype humidex that takes local conditions into account, into its plans and guidance for residents during heat events.

“Previously, our guidance was based solely on the temperature,” said Cole. “In general, the more information we have regarding extreme heat and how it impacts health, the better able we are to provide guidance during heat events and target resources to those most at risk.”

Heat risk pales in comparison to other climate concerns, said Dr. Greg Thompson, Whatcom County’s co-health officer. He practices in one of the four climate regions where the mortality rate rises most quickly as days get hotter.

“In Whatcom, we don’t experience the number of heat-related deaths that are seen in hotter parts of the country – in fact they are uncommon enough that we have not been regularly tracking them,” Thompson said. “As the study suggests, however, we expect that heat-related injury and death will increase as extreme heat days increase. Locally, poor air quality due to wildfire smoke has likely had a larger health impact than high temperatures.”

This data could spur health authorities in affected areas to invest more heavily in heat-illness prevention efforts for people in the most affected demographics, or help their offices or other leaders lobby for the funding to start or continue climate-adaptation projects.

Jefferson Ketchel, executive director of the Washington State Public Health Association, says that local health is improving the ability to be proactive rather than reactive to heat stress, but that funding is not yet sufficient to meet the need. He points out the large impact of heat on metro areas with high numbers of unhoused residents, sparse air conditioning and inequitable and insufficient access to green space, like King, Pierce and Spokane Counties.

“One of the challenges we generally see is that when people are proposing climate action plans, they're generally sold as too expensive,” said epidemiologist Cunningham. “[But] when you see the [heat risk] projection data, you start to paint a picture of how expensive it is to not do it, which is often quite a bit more expensive.”

The study, Cole said, emphasizes that ultimately everyone needs to do more work to prevent further warming.