During a routine survey near the Hoh River in Jefferson County in 2011, Rocchio looked out beyond the bog laurel and bog labrador tea at the edges of a 40-acre wetland and its secret almost registered: The shrubs at the center were taller than where he stood. Just taller, thicker shrubs, he’d thought, heading toward them.

“And then I got out there. And that's when I had this moment of like, ‘Oh, my goodness,’” he says. “It just kind of clicked.”

It wasn’t the shrubs that were taller; the ground was, and it was somehow wetter. The bog sloped downward ever so slightly from the center. He was standing on top of a raised bog, which wasn’t supposed to be here.

This unique ecosystem is built on the backs of decomposed mosses and entirely fed by rainwater. The next-closest raised bog is in British Columbia and no others exist in the coterminous Western United States. Places like Crowberry Bog, named for the hardy crowberry plant that sheds its fruit there, get scientists excited because these sometimes overlooked ecosystems are home to some of the most unique native plants and greatest biodiversity in the state.

As soon as Rocchio realized what he was looking at, he began nominating the bog for the state’s Natural Areas Program, a managed collection of rare and exemplary ecosystems. But just as the program celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, climate change is threatening its ability to keep our living heritage safe from fire, higher temperatures and other threats.

Ecologists like Rocchio, who manages Washington’s Natural Heritage Program, are racing to keep that biodiversity from disappearing. The program develops the rare plant and ecosystem databases and conservation priorities that feed directly into Natural Areas designations, among other state and federal natural resource policies and decisions.

Without adjusting how Washington sets conservation priorities, Rocchio says he’s “pretty certain” species and ecosystems will disappear from the state.

A fragile legacy

The Natural Areas program, launched in 1972 with the Natural Area Preserves Act, required the state to create and protect a menagerie of the outstanding sites reflecting Washington’s natural heritage. Preserve designation goes to sites representing the best-functioning examples of native ecosystems, unique ecosystems rare plant communities or plant species, and sets them aside for research and posterity. The program also protects Natural Resources Conservation Areas, which also have high native habitat value but allow for recreation.

While many conservation programs focus on protecting as much land as possible, the Natural Areas program is all about legacy. Like Noah with his ark, the Washington State Department of Natural Resources collects the best and healthiest examples of ecosystems and rare native plant habitats, aiming to protect at least one representation of each, an open-air blueprint for conserving similar areas.

The Natural Areas program was created to protect these places from threats like human development and overuse, especially important as the state’s population has nearly doubled over the past 40 years. This special designation limits visitors to these areas, often requiring research permits to visit. As a result, any changes that happen within these protected ecosystems can be largely chalked up to climate change, and provide baseline data for managing and restoring similar spaces.

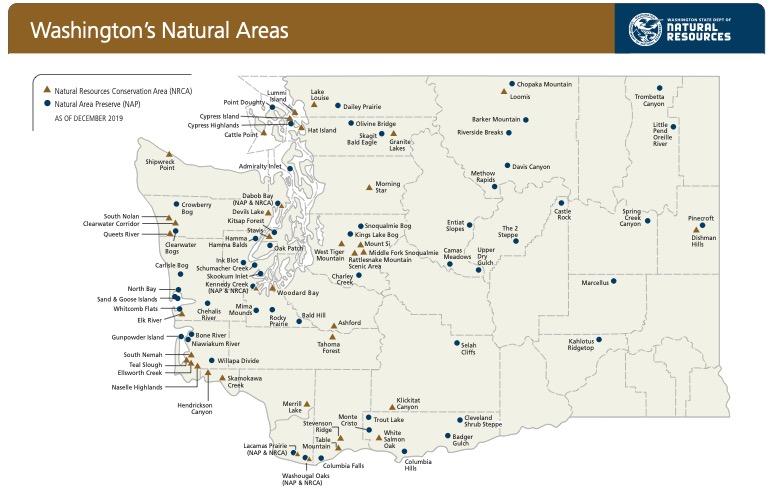

The state’s natural resource department currently protects more than 166,400 acres of land where these rare, unique or extremely intact ecosystems are found across 97 total sites. According to one state estimate, these areas conserve “the habitat of at least 80 vascular plant species of special concern in Washington and 126 ecosystem types of high conservation significance,” including grasslands, ponderosa pine forests and vernal ponds. (The department manages the majority of Washington’s 215 Natural Areas. The state’s Department of Fish and Wildlife and parks department, Washington State University, nongovernmental organizations and several federal departments manage the rest.)

While the Preserves Act directed conservation of “undisturbed” ecosystems, ecologists have since recognized that many Indigenous cultures stewarded Washington ecosystems for thousands of years. Although most of these Natural Areas are off the beaten path and limit access to researchers only, other popular sites like Mount Si and Tiger Mountain reconcile conservation goals with people’s desires to hike, bike, camp and otherwise appreciate the state’s natural legacy.

But the biggest threat a half century later — climate change — can’t be stopped with a fence, especially at places like Crowberry Bog. Being entirely rain-fed, slight shifts in climate could make it unrecognizable.

“It's exasperating all the stuff we're already managing for, and that’s the big concern,” says Rocchio.

Small, pink bog laurel blooms rest on a bed of peat mosses under a canopy of bog labrador tea, a native shrub. More than 2,600 native vascular plants, thousands of mosses, lichens, liverworts and fungi grow in the state, and 84 plant species are found entirely within Washington. (Hannah Weinberger/Crosscut)

A skunk cabbage nestled into the peat mosses at Crowberry Bog, a protected rare ecosystem in Washington state within the Natural Areas Program. Partially submerged skunk cabbages create their own “micro-habitats,” says ecologist Joe Rocchio, who works with the state’s Natural Heritage Program, full of different moss flora. (Hannah

The 40-acre bog is layered with red, orange and green sphagnum mosses, giving the wetland the appearance of a dated shag carpet. The carpet compresses with each step Rocchio takes, like a waterlogged memory foam mattress that springs back into place as he removes his weight. The less decomposed, the springier, says Rocchio, who’s become personally invested in the bog.

“I’ve come out here so many times, [my kids are] like, ‘Where’re you going dad?’ ‘I’m going out to the bog.’ So slowly over time it became daddy’s bog,” he says.

That passion pushes Natural Heritage program ecologists to avidly classify, inventory and study native flora to help protect them as efficiently as they can. While the Heritage program focuses on plants and plant communities, particularly rare ones, conserving habitats important for plants can benefit other living things.

Considering the importance of biodiversity, it’s a big job.

Ecosystems can often keep functioning well even when some species disappear. After enough losses, however, they fundamentally change. Those functions, or ecosystem services, include regulating water, offering habitat for pollinators, filtering nutrients and serving as carbon sinks.

“So having a diversity of species that play different roles and do different things is important to keep those ecosystems functioning,” says Dr. Joshua Lawler, a conservation-focused ecologist and professor at the University of Washington, who has prepared reports on the relationship between climate change and biodiversity in the state.

The Natural Areas site designations have been hugely efficient so far, Rocchio says. Last year, program ecologist David Wilderman analyzed them and found that these sites, which account for about 0.4% of the state’s landmass, represent members of nearly 60% of the state’s native plant species.

But climate change requires an updated approach so state ecologists can understand how many rare species and ecosystems are extremely vulnerable to climate change.

Rocchio says this is why he’s passionate about monitoring them. “We need to measure these changes we think are happening, because oftentimes things are happening in non-intuitive ways,” he says.

A map of Natural Areas sites in Washington state. These sites represent the most intact, best functioning examples of native ecosystems, as well as the homes of rare and unique ecosystems and plants. Natural Area Conservation Areas offer opportunities for education, research and recreation that put ecosystems on display, while Natural Area Preserves often limit access to protect the most vulnerable plants and ecosystems. (Courtesy of the Washington State Department of Natural Resources)

Resources to do that monitoring have diminished. The Natural Areas budget decreased from an inflation-adjusted $4.5 million just before the 2009 recession to $2.9 million today, with staff decreased from about 19 full-time employees to 11. The Natural Heritage Program budget decreased from inflation-adjusted $2.5 million to $1.7 million over the same time period, while full-time staff halved from 12 to 6 people.

Though Rocchio is hesitant to make predictions about ecosystem change, some have more “obvious” futures than others, like alpine ecosystems. “We suspect that they're not going to be doing well over time because they don't have anywhere to go. They're gonna basically be kicked off the mountain.”

While many people generalize that wetlands will all disappear, Rocchio says it’s more nuanced than that. Some research, Rocchio says, shows groundwater wetlands may be more resilient over the next 50 years, while rain- and surface water-fed wetlands like Crowberry Bog will see huge impacts.

There, ecologists think warmer winter conditions, drought, decreased precipitation and longer summers may change the bog’s ecology, removing the one example of a raised bog in the conterminous Western U.S. Trees like the native western hemlock or shore pine, for instance, may encroach on the bog as parched mosses recede. But soaring temperatures like the heat dome of 2021 could instead scorch young trees, as ecologists saw in a different bog that year, and neutralize some growth.

The state regularly publishes Natural Heritage management plans to explain how it characterizes ecosystems and plants, and determines their rarity and prioritizes them for conservation need. This helps designate new protected sites and how Natural Areas ecologists will manage the species within them. The 2022 plan does this more explicitly than past ones, where climate change was briefly mentioned.

“We have to bring climate change into this decision-making process,” says Rocchio, a first-time author of the report. “Previously … I think we were just challenged as to how that would actually work and happen.”

Planning for climate changes

The new Natural Heritage management plan takes a stab at incorporating climate change into that process.

One key way is reconsidering how granular to get when classifying ecosystems. Zooming in on smaller differences between ecosystems could better capture aspects of them that climate change might affect. As an example, consider a pair of hypothetical forested wetlands. They’re all technically the same, at a coarse level — but they might receive water in different ways. The forested wetland located on a slope where groundwater is emerging might respond differently to climate change than the forested wetland on a river where it meets the tides.

“[If] we protect examples of all … of those, we’re giving forested wetlands a chance” under different climate scenarios, Rocchio says. “We know that climate change is going to force plants and animals to seek refuge in a more hospitable place, and we've tweaked our targets for ecosystems to really do that.”

Beyond simply better characterizing species and habitats, the plan calls for more information about how vulnerable these places and plants are to climate change. That’s where a new tool adapted from the nonprofit NatureServe comes in. The Climate Change Vulnerability Index, and a sister tool used for comparing habitats, describe species’ exposure to climate change and sensitivity to climate impacts.

“If you have two imperiled species, one extremely vulnerable to climate change and one not, all else being equal, that's really helpful to [inform] which one we protect,” Rocchio says.

Heritage Program rare plant botanist Walter Fertig is at least halfway done assessing Washington’s suite of rare plants with the tool, Rocchio says, but assessing ecosystems and relationships between their dozens of elements is harder. “We're behind, and part of it is we don't have a good method yet,” Rocchio says.

Heritage ecologists aren’t the only state employees trying to figure out how habitats will respond to the climate. The Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife develops a State Wildlife Action Plan every 10 years. The most recent plan from 2015 includes a climate vulnerability analysis for species, as well as key ecosystems these animals depend on. Fish and Wildlife officials are kicking off their next 10-year update, according to the department's climate change coordinator.

It’s hard to predict how the Heritage Program will end up factoring this information into its assessments — and ultimately, how much of a role it will play in land use decisions like the Natural Areas program. The Natural Heritage program is advisory only, but its work influences how the state pursues purchasing land within boundaries of ecologically important areas, and often also influences the Endangered Species Act and Washington’s Growth Management Act. It can lead to management decisions that help sites resist or reduce damages in the face of change, such as widening site boundaries to remove nearby disturbances, taking action against invasive species or reversing ditches, drains or other infrastructure that interrupt natural functions.

In dire cases, though, it might mean helping a site transform to serve other species moving in as climate change forces them to migrate.

Joe Rocchio walks through Crowberry Bog, a unique wetland in Washington state, where a series of research projects are set up. Some use a series of pipes to measure water pressure, like those seen here, which scientists DIY’d from PVC pipes. Some pipes exhibit signs of being chewed upon — hopefully by wildlife. Depending on the pressure, scientists can get a sense of where water is coming from. (Hannah Weinberger/Crosscut)

Coping with lost heritage

Climate change prompts an uncomfortable possibility: The Natural Areas conserved for the past few decades may not survive the climate crisis. Rocchio understands how putting conservation resources into a site that’s liable to change might seem misguided.

“It's a valid question,” Rocchio says. But even with losses to climate change, any land conserved is land conserved, and climate change doesn’t preclude one mandate of the Natural Areas program: to manage controlled research sites.

Crowberry, being entirely rain-fed, could be a candidate for the research approach.

And even transformed ecosystems have a lackluster silver lining. Studies show protected areas tend to provide better refuge for uprooted species than unprotected ones do.

“I think every bit helps, and even small parcels can act as a stepping stone and help connect bigger pieces of protected land,” UW ecologist Lawler says. “Having places [for species] to go where people aren't, is a key element.”

Or as Wilderman puts it: Even if these ecosystems become unrecognizable, they’ll likely be the most functional ones we have.