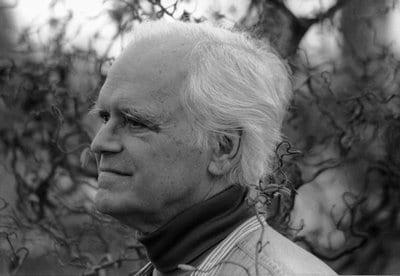

As a poet, teacher, editor and author, Wagoner shaped a poetic identity from the Northwest’s natural and cultural surroundings, just as midcentury architects like Paul Thiry and artists like Morris Graves and Mark Tobey created modern works rooted in the region.

Through books published from the 1950s onward — poetry, novels, plays — and years as an influential University of Washington professor, Wagoner had a deep and deeply felt influence.

Wagoner figured in my own life. My mother, Margi Berger, was a poet. She admired Wagoner’s focus on the lessons of nature and the wilderness in his work. She was a fan of Wagoner’s mentor, Theodore Roethke, the region’s adopted poet laureate who taught at the UW, drank at the Blue Moon, and whose legacy continued for decades after his death on Bainbridge Island in 1963.

Because of my mother, our home was filled with the works of Roethke, Wagoner and other regional poets, including William Stafford, Beth and Nelson Bentley, Carolyn Kizer and Richard Hugo. These were poets of national stature who emerged from what was once considered an artistic frontier or the legendary “aesthetic dustbin.”

For many years (1966-2002) Wagoner edited the hugely influential Poetry Northwest magazine, the high-bar journal that shaped and published regional voices through his lens. During that period his own work gained national attention and his poems were frequently found in publications like The New Yorker. National Book Award nominations and other awards and accolades accrued.

I remember watching Wagoner glide into a party in the late 1960s at a Pioneer Square gallery opening. He was like a swan among coots. He was handsome, confident, aloof. When I spent a weekend teaching at a writer’s workshop on Whidbey Island a decade ago, Wagoner was on the faculty, too. When we lunched together, I discovered he was anything but aloof: gentle, curious, approachable, committed to craft. Wagoner continued to teach younger writers, including at Seattle’s Hugo House.

He also maintained his connection to Roethke, wading into the brilliant, stormy poet’s notebooks and organizing the fragments into a wonderful collection, Straw for the Fire. In 2007, he wrote a play, produced at ACT Theatre, called First Class, in which the legendary Seattle actor John Aylward played Roethke — a performance Wagoner said was “uncanny” in its portrayal of the poet. Wagoner hoped his play would capture Roethke’s charisma in the classroom, and, for those who attended, it did.

But Wagoner’s own work was unique and fully his own. He did not adopt his mentor’s intense persona and instead maintained a more cerebral, contemplative posture with less demon-wrestling.

Originally from the tamed Midwest, Wagoner dove into this region’s forests. He was inspired by the sea and wildlife, too. He walked trails in a kind of balancing act that, for many, captured the experience of the Northwest wilds: a place of ancient gobsmacking beauty that puts you in touch with nature as robust, yet fragile. A place to experience awe, but also to reflect on our tenuous relationship with it.

Some national critics considered him a “nature” poet or an “environmental” one. Wagoner was more: He brought a modern intellect, a mix of passion filtered through detachment that kept his work from being a syrup of paeans to the pines. His work has been lauded as “a remarkable fusion of nature, legend and psyche.”

The title poem from his 1966 book Staying Alive is, to me, a standing monument to what he brought to the form, though by no means is it an endpoint of his work, which continued many decades after. It’s presented as advice on how to stay alive in the woods if you are lost. However it clearly stands as advice not just for hikers, but for the journey of life, which can leave us stranded. No fragment would do it justice so be sure to read the whole poem, not just this excerpted bit from the end:

You say you require

Emergency treatment; if you are standing erect and holding

Arms horizontal, you mean you are not ready;

If you hold them over

Your head, you want to be picked up. Three of anything

Is a sign of distress. Afterward, if you see

No ropes, no ladders,

No maps or messages falling, no searchlights or trails blazing,

Then, chances are, you should be prepared to burrow

Deep for a deep winter.

One critic called it “one of the best American poems since World War II.” It has particular resonance now, when the pandemic and politics have left many feeling lost in the deep woods, off trail and with unreliable rescuers.

Northwest poetry has grown well beyond the straitjacket of woodsy themes, cool observation and the contemplations of old white college professors. It is more robust, more diverse, and perhaps it feels less tailored for outside approval, too. Local poet laureates dot the landscape from Redmond to Spokane, including Washington state’s current and first Native American poet laureate, Rena Priest.

But the cultivation of a Northwest commonality leaning on place, on growing roots, of exploring life at the edge of the continent with a contemporary eye, this is part of our legacy, one encouraged and invigorated by David Wagoner.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.