The monthlong annual arts event, organized by the city of Redmond in its Downtown Park, is meant to celebrate the “winter holiday traditions, cultures, and faiths of the diverse Redmond community,” according to the city’s call for art. It was Sourour and Khalaf’s first public artwork, the capstone of months of work.

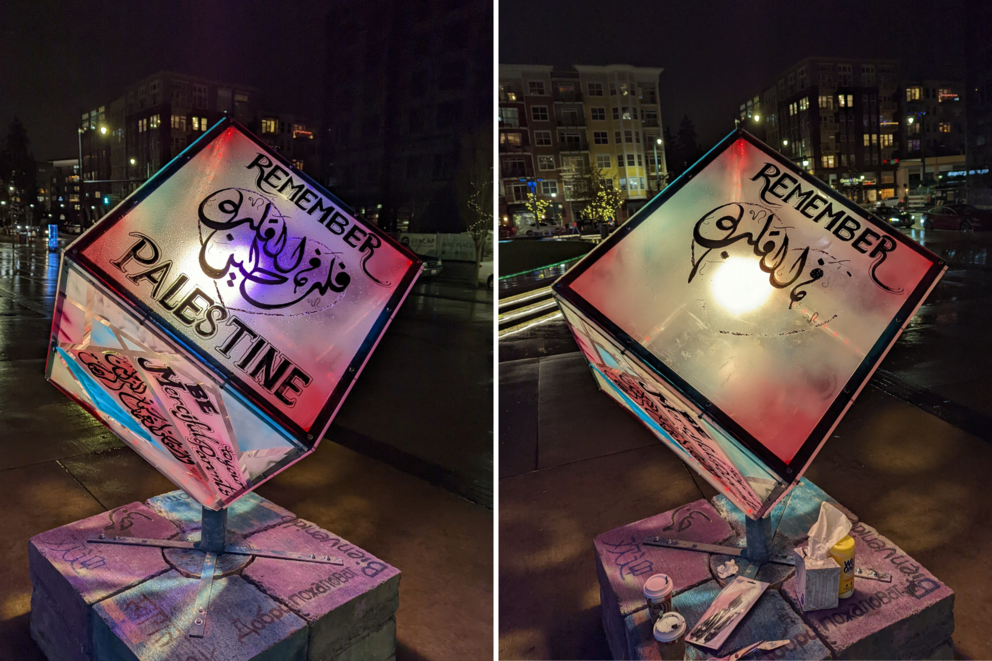

Along with other statements, including “No to racism” and “Compassion, forgiveness, patience, mercy,” one of the cube’s faces featured the statement “فلسطين†في†القلب†,” which transliterates to “Palestine is in the heart,” along with the words, in English, “Remember Palestine.”

A few hours after completing the installation, the duo’s joy had dissipated. Instead, Sourour and Khalaf felt a deep sense of disappointment as they blacked out the word “Palestine,” in both Arabic and English. Later, after the rain had washed the paint away, they scratched off the letters with the metal edges of a pair of scissors and palette knife.

The artists, both Egyptian software engineers and calligraphy artists living in the area, said they were told through the city’s cultural arts administrator, Chris Weber, that the word “might be considered political, or offensive to some,” Sourour and Khalaf said. (Weber declined to be interviewed for this story.)

Internal emails obtained by Crosscut through public records requests show that Weber showed concern soon after installation. “FYI, this is the ‘globe’ much different than expected. Possibly some concerns?” Weber wrote, attaching two photos of the face of the cube that said: “Remember Palestine.” That email got forwarded on to the city’s parks and recreation director, Carrie Hite. Zach Houvener, the city’s Recreation Business Manager wrote back: “Yes, I do have concerns. That really is not what RACC [Redmond Arts and Culture Commission] signed off on is it?”

There were two brief phone calls between Hite and Weber in the following hours. Less than three hours later, Weber sent an email to Hite and others containing photos of the artwork with text blacked out (and other photos), noting: “The 'Remember' panel now says 'heart' in Arabic,” and discussed the details with Hite. The obtained records did not include any complaints about the artwork received before the city asked the artists to remove the text “Palestine.”

The artists said their freedom of expression had been curtailed. “We were instructed to either paint over it, or remove the panel or scratch it out, or else risk the entire art project being removed,” Sourour said during an interview Monday evening. After arguing their case in vain, the artists said, they eventually complied because they didn’t want to remove the entire artwork. “We were going to comply, of course, because these are the instructions from the public city-state, but we weren't happy with the instructions,” Sourour said.

“Rather than ending the night in a celebratory mood, we sort of spent it consoling each other while we vandalized the artwork we spent a month and a half building,” he said.

“It was a very upsetting moment for us,” Sourour added. “We came to the United States believing — and we still believe in this — it's a country where you're free to express yourself, you're free to express your identity.”

In a statement released Tuesday, the city’s parks and recreation director, Carrie Hite (who oversees the art department and also declined to be interviewed for this story), apologized to the broader community but not to the artists specifically. “The goal of the city staff’s actions were not to participate in the active erasure of Palestinian voices and culture,” Hite wrote. But she maintained the city was blindsided by how the artwork differed from the artists’ original proposal, which planned something astronomy-themed. In an email on Tuesday, Redmond city communications manager Jill Smith said the phrase on the artwork “could be considered by some to not fit with the theme of the event.” (Smith declined to clarify who she meant by “some” and said the altered artwork would remain on view).

But in a second statement, released on Wednesday, Hite backtracked from this decision to leave the erased work up, saying the language would be restored. “After further discussion, discernment, and conversation with one of the artists, I better understand the meaning and significance of the original message for the artist and many of our Palestinian community members,” she wrote. “After the past few days, it has become clear to me what the removal of the words 'Remember Palestine' means to community members, and for that I offer my deepest apologies….After more reflection, it is important for this celebration to honor the artists [sic] process and product.”

“The intent was not to cause harm to anyone; but it has become clear that harm was done,” Hite continued. “As we seek to do our part to ensure all community members have a sense of belonging, the artist will restore the artwork.”

The course reversal came after conversations with local Palestinian community members and groups like the Council on American Islamic Relations (CAIR) Washington.

"I greatly appreciate the response from the city," Sourour wrote in an email on Wednesday. “I thanked the director when she called me on the phone, and I got a call from Chris [Weber], the event project manager to coordinate with me about a time to go and restore the art piece. He was very supportive, offering a canopy and a heater to hasten the drying of the paint when we implement the restoration. I appreciate that very much, and it was unfortunate that this had to happen at all from the beginning.” On Wednesday evening, the artists finished repainting the work and restored it to its former state.

Artists Amal Khalaf and Omar Sourour pose with their work on Dec. 10, 2021. As Egyptians and Arabs, Sourour said, he and Khalaf wanted to show their love for the region and its people, given that it’s been “through a hard time.” He compared it to showing extra love to one of your kids when they’re sad. “This is just a declaration of love to a part of our identity, one that is definitely honest … [and] free of any hate speech.” (Omar Sourour and Amal Khalaf)

For the artists, the festival provided “a wonderful opportunity for us to share part of our culture,” Sourour said in the interview on Monday. While both artists are Egyptian, they said they feel a connection to Palestine. “We share deep roots of history, culture, music, food…. We have family, we have friends that are Palestinians. So Palestine is undoubtedly an integral part of our identity as Arabs and specifically as Egyptians,” Sourour said.

The artists, who didn’t have any public art or commercial art world experience, had felt encouraged to apply after attending the city’s free, three-day public art workshop (modeled after the city of Seattle’s program) meant to open up the field of public art — which still often skews white and male — to a more diverse set of artists “who can create culturally relevant artworks that represent the diverse population of Redmond.”

Their original plan, submitted to the city of Redmond in writing and during a subsequent meeting, consisted of a cube surrounded by a circle, inspired by ancient astronomical tools like astrolabes and Islamic armillary spheres. The proposal stated the cube would be covered in “Arabic calligraphy of different scripts with different origins in the Middle Eastern world (Ottoman, Persian, Kufic, etc.).”

“We had freedom on what to write on the glass sheets whether it be astronomy related or not, as long as there was no hate speech,” Sourour wrote in an email. He added that during the city's public art training, artists had been encouraged to avoid any offensive terms as well as anything “political.” (The city did not respond to questions about this.) Because of budget constraints, the duo shifted some of the work’s themes to better fit a pared-down shape.

To Sourour and Khalal, the words “Remember Palestine” are not political or antithetical to the festival’s mission, let alone potentially offensive. “We are not stating that we want freedom for whoever or want this to go down or this to go up or this to succeed…. There was nothing of that sort, just: ‘I love this country.’ I'm pretty sure had it been Canada, for example, … I wouldn't be having this conversation with you right now,” Sourour said.

Whether to officially recognize Palestine as a country has long been a point of contention in international politics. A total of 138 United Nations member states have recognized Palestine as a sovereign state, but the United States does not.

“We are trying to convey a peaceful meaning,” Khalaf said. “Why [can’t] the Palestinian community express their identity in public?”

During the public art bootcamp, one of the examples shown said, “Black Lives Matter,” Khalaf notes. “It was fine; it was also talking about a specific identity. And we thought: This is also sort of freedom of speech,” she said.

Although freedom of expression is protected by the First Amendment, the legal issues are not always clear-cut. In signed indemnity agreements with the artists whose artworks it displays, the city of Redmond usually reserves the right to remove artworks at its discretion, if it finds the work is “inappropriate or incompatible with the public uses of the city's property.” The city’s standard contract also stipulates that the city is not creating “a public forum or designated public forum for protected First Amendment expression under the Washington or United States Constitutions.”

The Redmond incident comes at a time when the debate over public art and monuments — and how, as a society, we should deal with artistic expressions that could be considered offensive, hurtful or polarizing — is intensifying. Governments and institutions around the country are increasingly finding themselves in the eye of a storm over allegations of censorship and curtailing freedom of expression or platforming of certain ideas.

In 2020, multiple artists accused Bellevue city officials of censoring their artworks, after descriptions referencing anti-Japanese events and sentiment in the city’s history had been edited or deleted from a public art festival in 2019. This preceded a 2020 incident in which a Bellevue College official whited out a mention of anti-Japanese agitation by Eastside businessmen that was included in a mural on the school’s campus.

Like Bellevue, Redmond — and the Eastside at large — has seen rapid transformation in recent years, both in terms of growth and and diversity (41.3% of Redmond’s population is foreign-born, more than double the rate in the Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue metro area at large). And, like Bellevue, Redmond aspires to become a world-class art destination to enliven the city and connect its citizens — to “nurture an ever-changing mosaic of contemporary cultural expression,” as the city’s Public Art Master Plan 2016-2030 reads.

As this master plan comes into focus and the city (along with the public art field) becomes more diverse, Redmond city officials have committed to changing some of its approaches. Chief among them is providing clear expectations and approvals for all artworks, “so that artists’ voices are elevated, respected, and in line with the goals of the various city sponsored events,” among other things.

Sourour is thankful the artwork is now restored, he said Wednesday evening. “It was a mistake to have that decision to remove the word Palestine,” he said. “But also it says a lot about them as people to retract that mistake as quickly as they did.”

This article has been updated to reflect public records received after this article's publication date.