The quote is from a 1919 op-ed by Eastside businessman Miller Freeman (1875-1955), who argued in The Seattle Star for the deportation of Japanese immigrants and an end to Japanese migration. But his name did not appear alongside the quote on the rock.

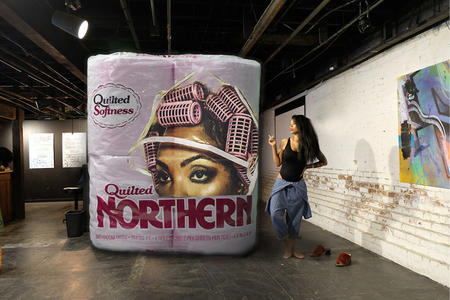

With the artwork, Seattle sculptor Khadija Tarver wanted to draw attention to Bellevue's history as a city built on the farmland cleared by Japanese Americans in the early 20th century. Her original proposal for the work contained Freeman’s name, more context — and more rocks. But that version was not on view during the 2019 edition of Bellwether, the annual arts festival organized by the city of Bellevue.

Tarver says she was asked to change the content of her artwork for the fall event, which features installations and events across four locations, including City Hall and Bellevue Art Museum. Two other artists involved — and one curator — also allege “censorship” of elements of their submissions.

Local writer Jim Snowden says he was asked to change two sections of a poem he wrote for the festival. Snowden and Tarver both say they were asked by the city, via curator Elisheba Johnson, to take out or change references to racism, the Freeman family and local anti-Japanese history.

“I couldn’t write his name, couldn’t carve his name into the piece… We couldn’t include the [Freeman] name in the title, either,” Tarver says. “It absolutely sanitized the work and intention.” Tarver says that’s why she decided to title the until-then nameless piece “Author Redacted, or The Seattle Star (1919).”

Snowden originally wrote, “You find it easy to forget how cruel you were just one grandmother ago, how you uprooted some of your people, drove them into camps, and sold what they had from under them.” That line later became: “But you’ve turned on the people who helped you build before,” among other changes. “I had to be more circumspect about it,” Snowden says.

A third participant, artist Erin Shigaki, says sentences referencing Miller Freeman and his grandson, Bellevue real estate magnate Kemper Freeman Jr., were taken out of the wall text she wrote to accompany her Bellwether sculpture, also on view at City Hall.

Shigaki was in the news recently, after an incident at Bellevue College (first reported by The Seattle Times) in which someone at the school whited out a sentence in a mural she had created that referenced anti-Japanese agitation by Eastside businessmen, including Miller Freeman. (The college’s president and one of its vice presidents have since left.) But Bellwether happened six months earlier, and in that instance Shigaki says not one, but three sentences referring to the Freeman family were removed before the descriptive plaque was printed.

Shigaki, Tarver and Snowden all say they feel censored.

Johnson, who had been hired by the city of Bellevue as one of the festival’s nine curators, described it as “a really screwed-up situation where we [the curator and artists] were told the artworks weren’t accepted for reasons we didn’t agree with.” Johnson says the only options she saw for herself and the artists were either to withdraw from the festival, or submit new concepts that would meet the city’s approval.

Internal emails obtained by Crosscut through public records requests show that the three artwork proposals by Snowden, Tarver and Shigaki, were “flagged” by at least one city official, though it is not clear why or for what precisely. The documents also show that people outside of the Arts & Culture program and additional higher-ups had knowledge of the situation, including Jesse Canedo, the city’s economic development manager, and Mac Cummins, the director of community development, the department that oversees the economic development and arts teams.

In an Aug. 16 email, a Bellwether administrator, Joshua Heim, updated Canedo, writing that the “stone sculpture calling out Miller Freeman and family will have no names on the inscription,” and noted that the text by Jim Snowden “had changed,” along with its location; it would now be shown at Bellevue Arts Museum instead of at City Hall.

Cummins and Canedo, as well as Bellwether manager Scott MacDonald, did not respond to requests for interviews. A city spokesperson sent a statement, which said, in part: “Over the course of the last several months city officials have had a series of meetings with the artist, including one facilitated by the local Japanese American Citizens League, and Bellevue has committed to improving future events. There have been valuable lessons in this feedback and the city has developed new processes and guidelines for the 2020 Bellwether.”

While Shigaki, Snowden and Johnson attended a JACL-led discussion with three Bellevue City administrators in December of last year, and had another virtual meeting (minus Shigaki) on March 16, the artists say the city has never acknowledged censorship, only apologized for the artist and curator “experience” and “miscommunication.”

When asked for a comment from Kemper Freeman Jr., the Kemper Development Co. recommended Crosscut contact the Bellwether organizers and said Freeman was "unable to provide more information."

After the March 16 meeting, Johnson said the city has come up with a thoughtful plan going forward, and that she’s “appreciative of the steps they are making to make a more transparent and artist-centered process.”

Crosscut talked to more than 10 people with knowledge of what transpired ahead of, during and after the Bellwether arts festival, which, in its new shape and second year, is and was meant to embody the vision of a cosmopolitan, diverse Bellevue. At the heart of the story emerging from these conversations: Bellevue’s history and future — and how both are inextricably linked to the Freeman family.

‘The godfather of Bellevue’

On sunny days, Bellevue shines like a hall of mirrors. To its west and east, Lake Washington and Lake Sammamish shimmer. In the city’s downtown core, glimmering glass towers reflect nearby high-rises and the sometimes-blue sky, enhancing the feeling that this city does not seem to think the sky's the limit. A city, officially one only since 1953, that grew quickly with wide lanes and tall towers, the surrounding bodies of water seemingly its only space constraints.

In the late 19th century, what would once become Bellevue was still an expanse of tree stumps. Farmers, mostly Japanese immigrants, uprooted what was left to generate arable land. Many of them leased, tended to and farmed those same lands for years (strawberries being the most famous crop) until “anti-alien” legislation prohibited numerous Japanese Americans from leasing land. After being forced into internment camps during World War II, many others lost the land they owned or leased.

Bellevue businessman and politician Miller Freeman played a pivotal role in that history, says Pacific Northwest journalist David Neiwert, author of Strawberry Days: How Internment Destroyed a Japanese American Community, which chronicles the history of Japanese American farmers in Bellevue. Freeman founded the Anti-Japanese League of Washington in 1916 and was “without question the leading agitator and organizer for anti-Japanese laws in Washington State,” including the 1921 Alien Land Laws and the 1924 Immigration Act, Neiwert says.

“He was unquestionably a white supremacist,” Neiwert adds. “He was constantly putting things in really stark racial terms and making Japanese immigrants out to be these demons.” He was also one of the leading proponents of internment in 1942, Neiwert says.

“What people like Freeman, but not just Freeman — the larger real estate business — gained by encouraging and basically demanding the removal of Japanese farmers from their lands was that those lands then were suddenly available for development,” he says.

Miller Freeman was “the godfather of Bellevue,” says Neiwert. The suburb of Bellevue, then newly connected to Seattle via a bridge Freeman advocated, was built on this land. “He founded modern Bellevue…. He’s the man who put up the money and basically co-founded Bellevue Square [shopping center] with his son, Kemper. That whole empire was founded on Miller’s work.”

Miller Freeman’s grandson, Eastside real-estate baron Kemper Freeman Jr., CEO and chairman of Kemper Development, oversees that empire now. Kemper Jr. has said his first memory as a toddler is of a bulldozer clearing the former strawberry farmland to make way for what would become Bellevue Square, then the region’s first suburban shopping center.

Another early memory, from when Kemper Freeman Jr. was just 5 years old: attending the Bellevue Arts and Crafts Fair, which was started by his grandfather. As Kemper Jr. grew up, the fair grew into a larger arts organization that spawned the Bellevue Arts Museum in 1975 and which now sits sandwiched in between various downtown Kemper properties.

Freeman has since become not just one of Bellevue's largest land owners and developers, but also one of the city’s major supporters of the arts. He’s donated millions to the Bellevue Arts Museum, as well as millions in direct donations and land to build the long-awaited PACE art center (which was known for a time as the Tateuchi Center until the Atsuhiko and Ina Goodwin Tateuchi Foundation pulled its funding).

He’s also a political donor. He supports the Republican Party nationally and locally, as well as Republican candidates, including President Donald Trump, and local anti-public transit initiatives, most recently backing lawsuits attempting to block the light rail’s expansion to the Eastside.

Perhaps ironically, the city wants to employ this new light rail to rebrand and catalyze a lively arts scene in downtown Bellevue by 2025.

By then, the city’s plan suggests, Bellevue, no longer Seattle’s suburb, will be a cosmopolitan art city in its own right. Its pulsing artery will be a “pedestrian and cultural pathway” dotted with cultural venues, sculptures, murals and artist-designed canopies, slicing through downtown from the light rail to the water.

“The opportunity is to put Bellevue on the cultural map as a first-rate city for art by connecting these discrete cultural treasures into something truly grand,” the plan reads.

The reenvisioning of the city’s biennial sculpture exhibition as Bellwether, a 10-day multidisciplinary art event, was meant to be the proof of concept for that plan. The city hired Seattle artist collective SuttonBeresCuller to help shape the art plan and rethink the festival, which the trio curated in 2018. Last year, they stayed on as creative directors and chose nine curators, mostly from Seattle, who curated various exhibits and programs. (SuttonBeresCuller has been hired for the 2020 edition as well.)

Last year, Bellwether centered on the theme of “taking root.” The prompt for proposals read, in part, "Bellevue is a place where new diverse communities have chosen to take root. What does it mean to put down roots, blend and merge cultures, and engage in aspects of community? What is the seed that we carry with us when we work to create a new home?”

As it turned out, the nine artists Johnson had tapped for display at City Hall also wanted to question what it meant to be uprooted.

‘You don’t want to remember, but you must’

For Bellwether 2019, artist Garima Thakur proposed I Am an Alien, an interactive computer game incorporating language from immigration forms. Tuan Nguyen made a series of comics about the idea of being an “illegal alien.” Michelle Kumata, Tarver and Shigaki (whose father was born in a Japanese American incarceration camp) sought to honor the strawberry farmers who lost their land during the incarceration following Executive Order 9066.

Poet Jim Snowden opted for a parody of Carl Sandburg’s famous poem “Chicago." Addressing “Bellevue, softwaremaker to the world, builder of malls” Snowden called out the Japanese internment — "You don’t want to remember, but you must" — and recounted a recent incident in which one of Snowden's Asian American students had to endure racist harassment while waiting for the light to change in Bellevue.

After Snowden sent his poem to Johnson in early July, she emailed back: “Whoa!!! This is freaking amazing and perfect!!! I love it!!!”

Soon after, during a tense, hourlong group phone call, it would become clear to Johnson that the festival organizers didn't necessarily agree, she says. While it wasn’t clear why, she says festival manager Scott MacDonald conveyed that some aspects of Snowden’s work were a problem. Basically, Johnson and Snowden say, the city argued it wasn’t factually correct to accuse Bellevue of racism or responsibility in the Japanese American incarceration when the city hadn’t even filed incorporation papers yet, which Snowden says “made very little sense to me.”

Johnson also says she was “told that she [Tarver] could not list the Freeman name.”

While memories of the phone discussion, and how explicitly things were said, vary, participants say they understood that future funding for the event could be on the line, and that the Freeman family was politically powerful. It was the first time the Bellwether team had to deal with explicitly political works — and the fact that these would be shown at City Hall, a government building, complicated things.

Ben Beres, the festival’s artistic director, who was on the call, says his memory of it is “muddy.” “I just knew as the creative director, you didn’t want to attack anyone, and there was this kind of general consensus on the telephone call that it’s probably not a good idea,” Beres says. “We want to say things, but we also don’t want to cause controversy, necessarily.”

Beres says Johnson was “not explicitly” told Tarver could not list the Freeman name in her work. He says “no naming names” was more of a “general consensus” than a policy. He says the phone call was a “tricky dance” where “things were trying to be said without explicitly saying it.” (Johnson says Bellwether manager Scott MacDonald told her explicitly she couldn't say the Freeman name.)

Asked whether he knew or explained to Johnson why there could be no “naming names,” Beres says “calling someone out” — Freeman or anyone else — just didn’t “feel right.” He also stresses that all of this happened amidst the frenzy of an understaffed and overworked group of people putting together a huge show in a new format. “There were tons of moving parts,” such as other artworks with sexually explicit content or the N-word, that needed to be adapted last minute, Beres says.

“It wasn’t malicious,” he adds.

Johnson says she considered quitting, as did Tarver and Snowden. But they decided to keep going, for various reasons. Quitting would mean no artworks and not getting paid. Participating with a diminished proposal was pushing the boundaries more than pulling back.

Internal emails show the city asked for a second version of Khadija’s and Swowden’s proposed text, but noted no reasons or ways in which the text would change. Snowden’s second draft, which he calls a “lesser version,” was approved. Over email, the city and Johnson called it a good and great “compromise.”

Tarver’s original proposal included the source of the “White man’s Pacific coast” quote, as well as these phrases, among others: By the end of internment in 1944, only 11 out of 60 Japanese American families returned to Bellevue. Miller Freeman gave son Kemper Freeman Sr. 10 acres of tenable land to build Bellevue Square.

After many phone calls, Tarver and Johnson say they landed on just using the single quote, without attribution. Johnson texted Tarver on July 30: “He is okay with the quote,” referring to, Johnson says, Bellwether manager MacDonald.

‘Don’t bite the hand that feeds you’

“It was made perfectly clear from the city of Bellevue [that artists] were not allowed to mention their [the Freeman] names, because it was too problematic,” says someone with knowledge of what transpired. The person requested anonymity, given the controversial nature of the situation. “You don’t want to bite the hand that feeds you.”

“It was very clear that people feel like they can’t say certain things,” Johnson, the curator, says. While it is “totally standard” for city-commissioned artworks to go through a revision process — for physical safety in the space, or foul language, or nudity, sexually explicit images or words, slurs — this was different, Johnson says. “Usually,” she says, in reference to Tarver’s piece, “facts are not an issue.”

Case in point, Johnson and Shigaki say: Shigaki’s sculpture — with the “censored” text on a plaque nearby as part of the sculpture — was on view for two months during a group show at King Street Station late last year (after Bellwether), organized by Seattle’s Office of Arts and Culture.

Still, in general, city governments have broad authority in this area, says Eugene Volokh, professor of law at UCLA who specializes in free speech law. “When the government commissions works in order to display them in government buildings, it’s generally seen as ‘government speech’,” says Volokh, meaning it’s considered the government’s expression of its own views — on which they can put any restrictions they want.

But much depends on whether the art show would be considered a “public forum.” In that case, the government opens itself up to the free speech of others — not just its own speech. “Then it can’t start picking and choosing,” art law professor Amy Adler explains in the Art Law podcast.

Regardless of legal standing, the Bellwether artists say they feel censored. “Basically we have a government entity hiring curators and then not letting them curate, in order to shape an arts exhibition to intentions that were never stated before, reasons that they’d never entirely come clean about,” Snowden says. “If it isn’t censorship, it certainly feels that way.”

‘Whitewashing’?

Shigaki feels the same way. On Bellwether’s opening night, she says she discovered her art plaque missing three pivotal sentences, edited out without her knowledge:

After decades of anti-Japanese agitation, led by Eastside businessman Miller Freeman and others, the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans included the 60 families who farmed Bellevue. The Freeman family was amongst the biggest beneficiaries of the appropriation of these farms. Today, the same family, headed by property developer Kemper Freeman Jr., remains a powerful force in Bellevue.

Shigaki says she knew the sentences could be a potential problem. But she never thought they’d take them out without telling her. To make matters worse, she says, she also discovered that the city had added a legal disclaimer to her art label without her knowledge. It stated that “The views expressed in the artworks are those of the individual artists and do not necessarily reflect the views, policies, or position of the City of Bellevue."

Beres says he takes responsibility for asking the sentences to be edited out of Shigaki’s wall text. Shigaki had been “made aware that putting up someone’s name wasn’t possibly going to fly,” Beres says, so he told the editor of the label texts, artist and writer Amanda Manitach, to take it out, he says. “Where it went wrong,” Beres says, “is not sending it back” to Shigaki. Though it is not common policy to send artist’s wall texts back for approval before an exhibit, Beres says, in retrospect, he wishes he had. He has apologized to Shigaki.

After protesting the deletions, Shigaki says it was made clear to her (through Johnson via Beres) that she could send in a new wall text as long as it didn’t have Freeman’s name on it. (Beres says he does not remember this.) Shigaki and Johnson decided to send in a new text that talked about the anti-Japanese policies without mentioning the Freeman name.

“I feel completely traumatized” by the experience, Shigaki says. “I feel it's directly related to the whitewashing that happened around World War II to my family, to the community.”

But, she adds, “I’m grateful to those of us who are working to dismantle white supremacy and refuse to allow any part of the Japanese American story be silenced.”

Natasha Varner of the Japanese American history nonprofit Densho believes that what the incidents at Bellwether and Bellevue College show is that “there's a force that wants to keep this history hidden. “So it's really concerning when you see systematic efforts to silence and literally whitewash aspects of this history,” she says.

“These acts of censorship in Bellevue are coming from individuals and institutions in positions of power,” says Varner. “What Erin [Shigaki] experienced over the past several months isn't new.”

“Right now, especially since our country is in a position where we're repeating some aspects of what happened to Japanese Americans during World War II, it's especially important that we have this history be out there and known — and that we really work to wrestle with the ongoing impacts of that history.”

Neiwert, the journalist, says “the suppression of information by the Freeman family and the people who do their bidding” has resulted in a general ignorance about Bellevue’s history. Kemper Freeman Jr., Neiwert says, has not been forthcoming about that history: “He’s never owned the legacy.”

“And you know what? We all have to own that legacy,” Neiwert says. “He’s not alone. He’s hardly unique.” He offers his own family history as an example: His great-grandfather stole Native American land during the Pocatello land run in 1902.

“Most white folks are in denial about their responsibility as far as their family histories go, and the way they’ve treated non-white people throughout all of our history,” Neiwert adds. “I think it is incumbent on all of us not to run away from it and pretend this history didn’t happen.”