Morphos — the genus of butterflies auroras belong to — have long been collected for their iridescent dorsal wings. Starting centuries ago, their slender bodies were pinned to the curiosity cabinets of czars, queens, bankers, diplomats and scientists. They are still popular possessions today, whether framed or inlaid in jewelry or displayed in bell jars.

But Seattle artists Redd Walitzki and Kari-Lise Alexander have come up with what they say is a more ethical (and cheaper) alternative for artists, crafters, aspiring lepidopterists and butterfly aficionados: lifelike specimens, made from paper, printed and cut in Seattle — which they sell across the world through their company, Moth & Myth.

Their butterflies are, in fact, flying off the shelves.

Moth & Myth’s collection of monarchs, Luna moths and five dozen other Lepidoptera (the scientific order that includes moths and butterflies) are now for sale in Seattle at Chihuly Garden and Glass and at Ghost Gallery. They're also at “ethical curiosity shop” Paxton Gate in Portland and two children’s stores in Taiwan. But 99% of the company’s sales happen through its website, direct to the consumer. Things have been going so well that two more people were recently hired to the small team.

“It just kind of exploded,” Alexander says. This past November alone, the company shipped about 18,000 specimens — some of which are replicas of endangered species — and overall sales have increased 35% in the past year. To accommodate the increased demand, the duo recently moved from a small SoDo studio to a spacious one in Belltown. “We were above a commercial kitchen and a bakery — which was incredibly fun because it smelled amazing — but it got way too cramped,” Alexander says.

The transition is not entirely complete, so the new digs feel somewhat bare-bones. Two sets of commercial-grade printers and laser cutters (plus a few tables) stand at the ready, but much of the 2,400 square footage doesn’t have a use yet. A sponge-painted bare wall awaits its future as a showcase for all of Moth & Myth’s specimens. For now, just two flutters of Mint Morphos sit on a pedestal and near the doorway, and one frame is filled with orange monarchs of various sizes. “We moved in a month ago,” Alexander notes, near-apologetic for the lack of butterflies.

The move from SoDo is a significant scale-up that will allow Moth & Myth to start offering art workshops, something Alexander says is a natural step. “A lot of times, we'll post tutorials on how to use our specimens in different ways,” she says. “One of our most popular ones has been the bell jars.”

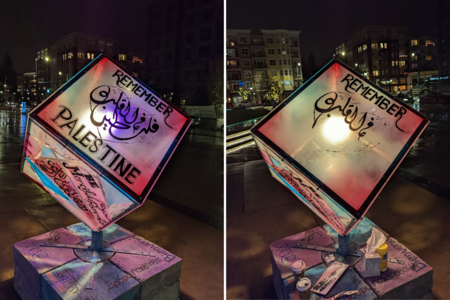

At Crosscut’s request, Jon Pelham, curatorial associate of butterflies at the Burke Museum, reviewed Moth & Myth’s website to assess the accuracy of the designs. “The company’s renditions are remarkably true to life and represent well-known ‘beautiful’ species,” he responded. All are identifiable.” Here, Moth & Myth’s Redd Walitzki displays several laser-cut paper replicas, including Morpho aurora butterflies and a Chinese water snake skeleton. (Lindsey Wasson for Crosscut)

At the new studio, Walitzki lifts the laser cutter’s glass lid and carefully picks up one of the just-cut butterflies, leaving a double-winged absence on the paper sheet. Gently, they position the 4-inch piece of paper in their palm and sway their hand back and forth under the lights. A shimmery turquoise explodes across the butterfly’s indigo wings, thanks to a holographic foil pressed into the printed paper with a letterpress. Walitzki flips the butterfly. Turned over, its wings are almost disappointingly parchment-tinted, with brown veins snaking through beige.

”This is specimen accurate,” says Alexander. “That’s what the Morpho butterfly will look like: incredibly colorful on the front … and then, because of the forest floor and to protect from predators, they’re camouflaged [underneath].”

Before founding the company, Walitzki, a painter and hobby entomologist, had always shown an interest in bugs, and would often depict insects and flowers in their work. Alexander, a friend and fellow painter, shared similar artistic proclivities and interests. (Both at one point raised caterpillars and butterflies in their own Seattle studios.)

One day, Walitzki recalls, “I was doing a portrait where I wanted to cover this live model with butterflies, and I couldn’t find any that were realistic.” Real specimens would have been too fragile. But their day job at a print shop came in handy. “It was like: ‘I have a printer here, I have a laser cutter. I’ll just try to make some.’”

After positioning the resulting paper-cut butterflies on top of a model for a painting, Walitzki started to wear the creations as jewelry or hair clips when attending arts events — where people would promptly try to buy them. When Walitzki relented and started selling the butterflies on Etsy, they sold out regularly.

The metamorphosis from hobby to business came in 2018. That’s the year Alexander came on board to help transform the “side hustle” into a business. Initially, she says, “We were really going at it from the entomology angle, targeting people that wanted to build specimen boxes and use it as an alternative to the living creatures, not realizing that really, our audience was ourselves: artists.”

Artists and craftspeople have proved to be especially eager buyers, Walitzki and Alexander note. Hair and makeup artists have embedded them in spectacular creations, jewelers cast them into resin earrings, photographers include them in their still lifes and bakers position them as if aflutter atop wedding cakes.

Though there are swarms of paper butterflies for sale on the internet, most are “kind of cheesy and not accurate to anything,” Walitzki notes. The duo spends months researching, drawing and fine-tuning the designs (in other words, they aren’t winging it), and that’s what they say sets them apart. Still, unlike in real life, the paper butterflies don’t have legs or antennae, which will certainly bug insect experts.

It’s about striking a balance, Walitzki says. “Sometimes, because our clientele is more artists and crafters, they will more go by color palettes. They might not care that it's accurate to a specific area, but they do want all the blue ones together.”

In December, Walitzki and Alexander premiered their first-ever gallery installation at Madison Valley gallery Roq La Rue. The show (extended through Jan. 8) features a swarm of 2,000 differently sized paper Morpho catenarii (aka “Mint morphos,” nicknamed for their lightly mint or blue-tinted white wings). Also included: morphos in various shades of blue and white, as well as Morpho auroras, which the duo shaped by carefully curling the paper around their fingers to make the wings appear lifelike rather than flat. Thanks to the variety of sizes, it looks like some of the insects escaped a butterfly farm and swarmed into the gallery, landed on the walls and ceiling and decided to stay. Others appear frozen in time under bell jars arranged on a faux ice cream cart.

“We’re hoping to do more installations similar to [Roq La Rue] and create that otherworldly, fantastical feeling that ordinary life just doesn’t hold,” Alexander says. “I personally would love to be more in the public eye in that way, to create really these fantastical scenes that can be done ethically, instead of using actual wildlife.”

Adding to that fantastical feeling and lately in high demand: birds, bees and beetles. This past year, Walitzki and Alexander expanded beyond Lepidoptera, including skeletons of snakes and frogs, too. At the studio, Walitzki holds up a small paper hummingbird. Its tiny, true-to-size body gleams with green foil, which is stamped with minuscule feather patterns.

“Birds, I found out, are very special to do because of the laws around taxidermy in the United States,” Walitzki says. “Taxidermists actually cannot do hummingbirds. They’re not allowed unless they’re for institutions or museums or stuff like that. We’ve actually sold quite a few hummingbirds to taxidermists as a replacement for their typical displays.”

But Moth & Myth won’t stop making butterflies. With 70 or so species represented in its collection, the company has barely scratched the surface. There are some 160,000 species of moths in the world, and roughly 17,500 species of butterflies.

“We probably think we’re pros about moths and butterflies,” Alexander says. “But then there will be a new species that we have never seen or heard of before — we will constantly be surprised.”

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.