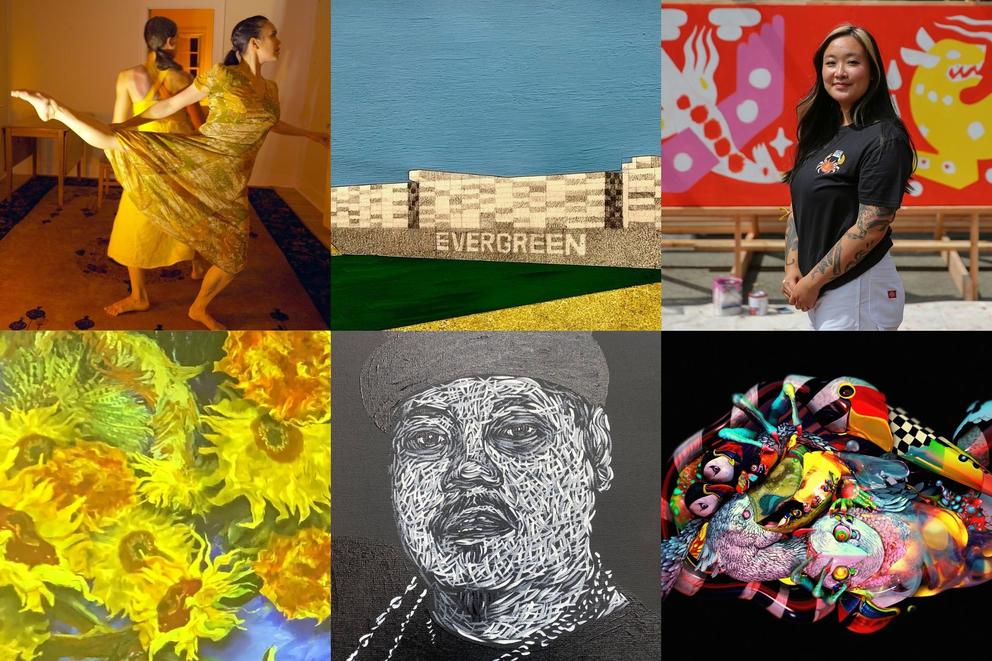

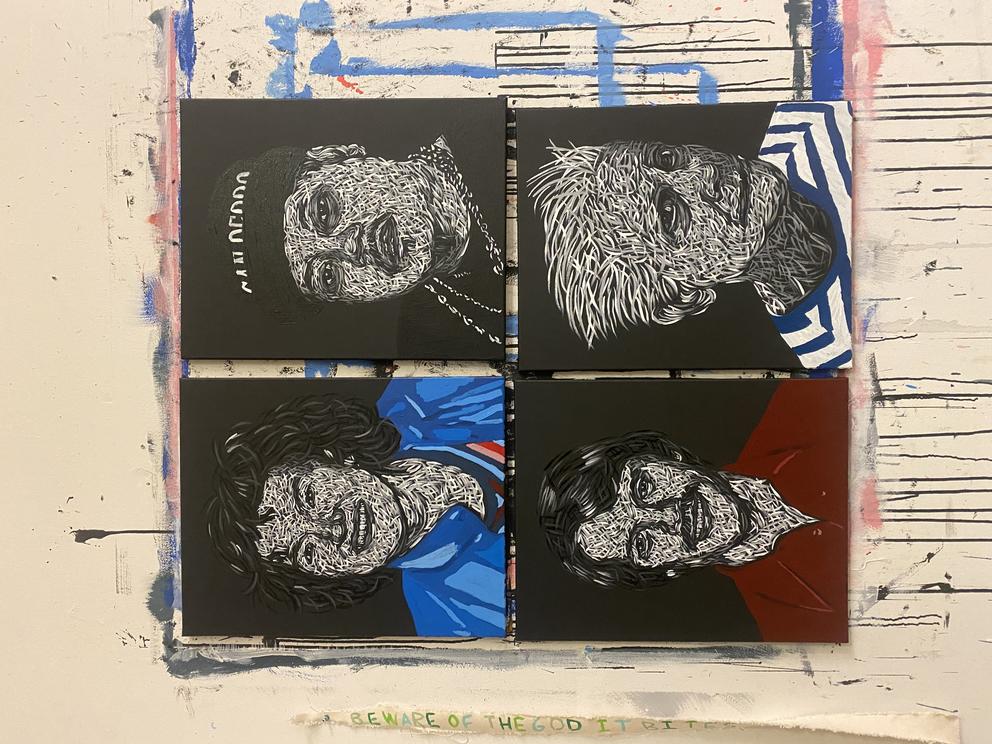

COVID-19 losses: ‘Reality Check,’ Baso Fibonacci

Earlier this month, the U.S. reached another tragic benchmark: Coronavirus deaths in the country surpassed 800,000. And now omicron is on the rise. Over the past year, various artists have tried to make sense of the pandemic’s inconceivable toll with flags, red felt roses, a quilt, lanterns and paper cranes.

But local artist Baso Fibonacci zeroed in on the faces of COVID, creating portraits of those we’ve lost. “I felt like the figure[s] you read about were so abstract,” says Fibonacci, who painted 20 portraits of local people who died during the pandemic in a series titled Reality Check. “The point of the paintings was to try and humanize the very real people who died from this illness,” he says. (The paintings are on view in South Lake Union until February).

Similarly, longtime Northwest artist Ries Niemi is at work on his Mute Project, a series of portraits of international musicians who have died from the virus — including John Prine, Manu Dibango and many lesser-known artists. Using a machine to embroider likenesses on handmade paper, Niemi began the series in April 2020 and has finished more than 130 portraits. But he notes that he still has “a list of probably 50 yet to do, with more being added all the time.”

Full immersion: ‘Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience’

Love it or loathe it, Van Gogh: The Immersive Experience, which arts and culture editor Brangien Davis described in her ArtSEA newsletter as “like stepping inside a screen saver of a painting,” was undeniably a major 2021 event. (Not least because ticket holders had been anxiously waiting for it to open.) But whether you can classify the much-hyped immersion room as an artwork is up for debate.

The exhibit — nay, experience — marks a shift in the public engagement with art. Much like the Seattle selfie museum that opened in early 2020, the phenomenon is symptomatic of a worldwide trend of surrounding ourselves with art, phone in hand.

And, get ready: More immersive experiences — maybe even a Banksy one — are on the horizon, a press person told us during our Van Gogh visit. And this spring, another immersive Van Gogh exhibit is coming to Tacoma. As for art the artist intended as an immersive experience, we lined up three 360-degree alternatives to the blockbuster show, two of which are still on view and well worth a visit.

Artist Casey Curran crafted a moving field of delicate flowers out of white, laser-cut polyester drawing paper. The installation, which moves thanks to a motorized pulley system, was on view early last year at MadArt gallery in South Lake Union. (Dorothy Edwards/Crosscut)

Eco-anxiety: ‘Parable of Gravity,’ Casey Curran

For “Parable of Gravity,” an early-2021 immersive installation at South Lake Union’s MadArt Gallery, Seattle artist Casey Curran constructed a forest of tall, Jenga-like fiberboard towers that appeared to have been partly destroyed — blackened by a meteor strike or some type of environmental collapse. These were topped with paper-cut white flowers, which fluttered open and closed via a motorized pulley system and sounded like the faint chirps of insects. Planned more than a year in advance but arriving on the heels of encouraging vaccine news and the Capitol Insurrection, the show felt eerily apt for the moment. Having just emerged from 2020 — a year of death and destruction — the show pulsed with a dystopian undercurrent hinting at environmental destruction and political chaos, while the flowers signaled a brittle hopefulness.

Also channeling our climate anxiety were local musicians, several of whom wrote songs inspired by Dune, the classic “cli-fi” novel by Tacoma author Frank Herbert. And contemporary writers shared environmental concerns, too, including Bellingham-based poet and Lummi tribal member Rena Priest, who pledged to bring attention to climate change and the loss of vital natural resources as part of her mandate as the state’s new poet laureate.

Street art: Cal Anderson Park mural, Stevie Shao

In a lipstick-red mural near Cal Anderson Park’s tennis courts on Capitol Hill, Seattle artist Stevie Shao painted a deer and rabbit dancing amid the flora. “Rabbits and deer live and feed in many of the same areas and have mutualistic feeding and alarm systems, where they rely on one another for cues over danger and food,” Shao told Crosscut in an interview for my profile of the rising street art star. “This relationship applied to the idea of ‘stronger together. ’”

Shao’s trademark vivid and flattened style became, along with Shao herself, ubiquitous in the city and on Instagram this past year. (She was also invited to paint Seahawk Russell Wilson’s cleats.) While the local resurgence of street art dates back to the COVID closures of 2020, Shao is among a small crop of muralists whose works have become recognizable in the city’s streetscape. Chief among these is the Black Lives Matter mural by the Vivid Matter Collective. In June, we caught up with the artists one year after they painted the most visible artistic symbol of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests.

Seattle also saw an increase in street art of a different magnitude and shape, with DIY micro-galleries popping up on Queen Anne sidewalks and in Capitol Hill alleys, uniting passersby in moments of spontaneous art discovery, right there on the street.

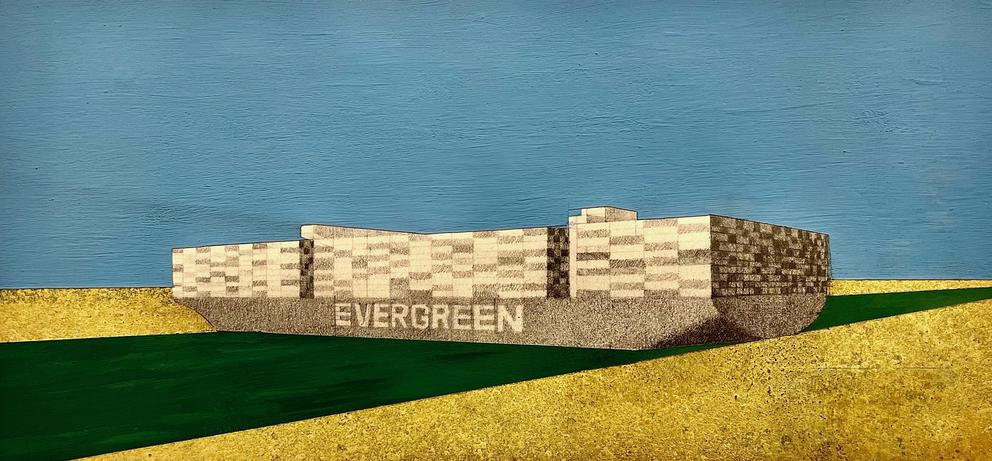

Supply chain struggles: ‘The Ever Given,’ Mary Iverson

Admittedly, “supply chain issues” doesn’t sound very sexy. But this complicated issue took a toll on people and industries across the world, including local exhibition installers, gallery owners and glass-blowing artists and much of the rest of Seattle’s arts scene. Also impacted: both Van Gogh exhibits (delayed because of supply chain snarls), bookmongers and painters, who ran out of blue paint.

But when that big ol’ boat — aka the Ever Given container ship — got stuck in the Suez Canal, corking a large share of the world economy, supply chain issues suddenly became a trending topic, as the vessel spawned excellent “memeage” and brought comic relief to our pandemic-addled brains.

For Seattle artist Mary Iverson, the ship also became a creative muse. Iverson — who, as Brangien wrote in her newsletter, was into ill-placed container ships and the complexities of the global shipping industry before it was cool — captured the vessel in graphite and gouache, as it struggled to get unstuck for days. “I’ve always wondered what the limit of growth would be,” Iverson told Brangien. “I’m pretty sure we’ve reached it!”

Seattle artist Sam Clover, aka Planttdaddii, made and sold this purely digital artwork as an NFT this past March, when the hype around the technology reached a fever pitch. (Sam Clover)

NFTs: ‘Feathered Friends,’ Sam Clover

In March of 2021, Seattle artist Sam Clover, aka Planttdaddii, sold this purely digital artwork — featuring a pile of trippy, 3D-drawn fauna and flora — for roughly $5,000, or 1.7 Ether, on the crypto platform Ethereum. Clover was one of many local artists who were able to cash in on the suddenly exploding NFT craze.

While not new, the crypto technology — click here for an explainer — quickly became a pop culture topic after a headline-grabbing, record-setting $69 million sale of a JPEG file at auction house Christie’s this past spring. The new medium also drew ire because of its hefty carbon footprint. Some local players tried to address the environmental issue from the get-go, such as Roq La Rue’s Kirsten Anderson, who started the NFT platform Phosphene in March with investor Art Min, promising to use carbon offsetting (though that technology has its limits).

Some of the NFT hubbub (or, as some call it, “speculation”) has since died down — and some of its “democratic” potential has been disproved — but local musician SassyBlack and painter Moses Sun have ventured into the crypto sphere, and an NFT museum is slated to open in Seattle early next year.

New visibility via public art: “78 on Jackson,” Paul Rucker

On a hot day this past summer, three older Black women took a break from grocery shopping to sit on a mint-green bench in the shape of a record player tonearm on the plaza in front of the Jackson Apartments. Part of a public artwork by Seattle artist-musician Paul Rucker, the 2,800-pound arm is affixed to an oversized turntable embedded in the concrete of the plaza, complete with a 12-foot diameter granite “vinyl” record etched with the names of 70 jazz artists, as well as 32 venues that once lined Jackson Street.

Rucker’s work was one in a crop of new public artworks by Black artists in the Central District — Seattle’s historically Black neighborhood — that helped anchor new developments with a sense of place and history. This influx of new sculptures and murals reflects a major shift in how local institutions are attempting to honor long-obscured histories, eclipsed stories and marginalized artists with major public artworks.

Also a result of this rethinking is a long-overdue regional surge in contemporary Native public art that honors Indigenous past, present (and presence) and future on the land, including new works by Andrea Wilbur-Sigo, Preston Singletary and RYAN! Feddersen.

Another expansive artwork that echoes with messages of presence and perpetuity: the city’s new AIDS Memorial Pathway, which rose up in the heart of the city this summer — 40 years after the start of the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

And, as the continuing pandemic made accessible outdoor art even more relevant, public art cropped up in the new Climate Pledge Arena, light rail stations, Seattle’s in-progress waterfront park and Seattle-Tacoma International Airport.

Music returns: Flotsam River Circus

To get why we were so excited by a ramshackle floating circus featuring flip-flopping dancers, acrobatic tricks, silliness, live music and puppetry that drifted into town for a few days — like a children’s book come alive and afloat — transport yourself back to this summer: It had been a long, lonely and sad 1½ years, COVID-19 cases were surging again and it felt like we were stuck in a loop we’d never escape. So: escapism felt pretty good.

As Brangien wrote in her newsletter: “The only answer is a floating circus, sea monsters included.” It was a literally moving show that happened while the live music/performance scene was still about as stable as a … dilapidated wooden raft.

A few other notable pivots that kept the music playing: Longtime U District music venue/dive coffee house Café Racer launched its own radio station (in advance of reopening on Capitol Hill this fall), a local nonprofit opened up its own, Seattle-based Indigenous radio station, and the Northwest African American Museum founded a gospel choir.

As the year progressed, music venues slowly reopened (jazz clubs were among the bravest and the first, while Belltown rock lounge The Crocodile just reopened in its new space this month). Still, not everyone felt comfortable going to live shows. Harborview nurse and Mudhoney bassist Guy Maddison told Crosscut contributor Charles Cross: “I choose not to go to any indoor shows…. I’m not ready to go back.”

And when Charles finally took the leap himself in November, he noted that while live music was definitely back on in Seattle, masks at many shows … were not.

Dance film: ‘Where you stay,’ Seattle Dance Collective

Choreographed by Robyn Mineko Williams, and featuring Noelani Pantastico and James Yoichi Moore, Seattle Dance Collective’s short dance video Where You Stay is moving in multiple ways. Filmed on Vashon Island, the dancers traverse the historic grounds of the Mukai Farm & Garden, a thriving strawberry farm in the early 1900s, which the Mukai family was forced to leave after Executive Order 9066 resulted in the incarceration of Japanese Americans in World War II. The film makes clear the rich potential of dance film, which can bring us into small rooms or wide-open places and up close with the dancers.

As one of the most literal of pandemic pivots, dance films blossomed into a sensation during the art form’s intermission in 2020 and 2021 — and they’re sticking around. Inspired by the “unprecedented explosion of digital dance creativity,” Pacific Northwest Ballet dancer Price Suddarth is hosting a dance film festival in March 2022.

Suddarth helped PNB pas-de-jeté onto the bandwagon, with The Intermission Project, a series of nine short dance films that feature PNB dancers sweeping and bending in Seattle parks.

And the dance films kept coming, from local dance-drag phenomenon Cherdonna Shinatra, who revealed what it’s like to be trapped in a small apartment with your own stage persona; from radio station KEXP, which brought both music and dance to the Paramount stage while the seats stayed empty; from local company Whim W’Him, which released five new dance films, including one set amid the industrial pipes of the Georgetown Steam Plant; and from dance festival Chop Shop, which for its final edition went all-digital with a slate of films like “Violet Crumble,” by Chop Shop director Eva Stone. As Brangien wrote, “her piece makes physical the mental process of coming through a traumatic event … through green grass and into a place of shelter.”

Local filmmaking: ‘East of the Mountains’ by S.J. Chiro

East of the Mountains has “Northwest” written all over it. The movie is directed by local film talent S.J. Chiro, based on the book by Northwest author David Guterson, and the starring role is played by Seattle’s own Tom Skerritt, whose face, as Brangien wrote in her newsletter, “is as intriguingly cragged as the basalt cliffs of the Columbia Gorge.”

The film premiered at this year’s (virtual) Seattle International Film Festival, a momentous comeback for a festival that had been forced to interrupt its 40-some-year run during the pandemic. Also in the lineup: the heralded premiere of Potato Dreams of America, local filmmaker Wes Hurley’s long-awaited feature film about growing up gay in Russia. These were among a pleasantly surprising number of local films that premiered during the pandemic, including Drew Christie’s short animated film about a beloved Seattle “outsider artist.”

In September, well after chain theaters reemerged, we were happy to see Seattle’s indie movie theaters open up for IRL screenings, as Crosscut contributor Misha Berson reported. It was welcome news for our pandemic-impinged local film sector.

Another glimmer of hope: a new soundstage facility on Harbor Island. Housed in the 117,000-square-foot industrial space that was formerly the Fisher Flour Mill, the new amenity is intended to help amp up local filmmaking, and is slated to reopen (after some upgrades) in early 2022.

Oh, and we spotted a mysteriously large number of new movies about finding (or looking for) Sasquatch in Northwest woods — perhaps a sign of how we’re all yearning for answers in this Age of Uncertainty.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.