“It’s for sure much cleaner,” says lifelong Seattle resident Cathryn Stenson, who has been walking through nearby parks more than normal to take advantage of the conditions. “I can see the Tiger Mountain radio towers from my apartment in Ravenna, and they’ve never looked this real and clear on stagnant days before.”

Stenson isn’t imagining it: People worldwide are starting to make observations of the unintended environmental impacts of the pandemic, which has infected more than a million people globally and taken more than 53,000 lives. But this positive change in global air quality is actually borne out by the data.

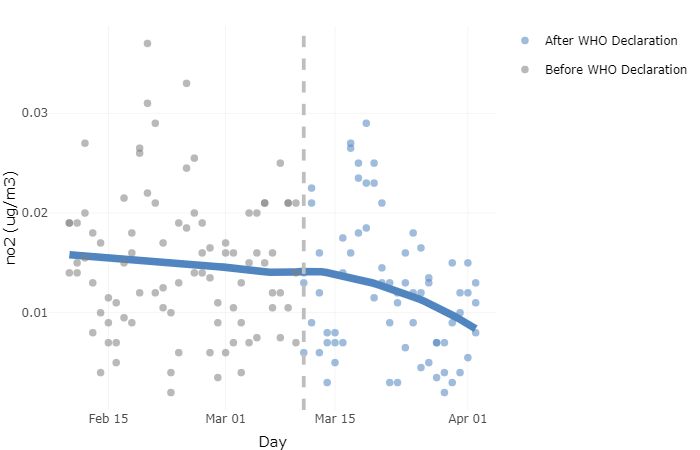

Beginning with China’s national lockdown and intensifying with the World Health Organization pandemic declaration on March 11, emission levels of key pollutants like nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxide and others have decreased, according to satellite data.

Some analysts estimate China’s national lockdown resulted in a 25% decrease of carbon dioxide emissions over a four-week period year over year. Italy has also seen emissions drop, and India — which has enacted the broadest lockdown yet — saw emissions drop nearly three-quarters within a week in New Delhi.

The decrease likely stems from multiple sources. Manufacturing and industry have slowed in countries under lockdown, and commuting and air travel have screeched to a halt in communities sheltering in place. In Seattle, the reduction in traffic is a major driver of that change.

“I think many of us who work in air pollution had a sense that there would be potentially some changes,” says Dr. Elena Austin, an assistant professor in the University of Washington’s Department of Environmental and Occupational Health Sciences. “And that's because we already know that the important sources, particularly for our area, are traffic-related. So if traffic is decreasing, potentially there would be a decrease in the ambient air quality as well.”

Typically when people talk about decreases in emissions, Austin says, they’re talking about industrial emissions like carbon dioxide and “criteria air pollutants”: six types of pollutants regulated nationally under the Clean Air Act. The six are nitrogen dioxide, sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, lead, ground-level ozone and particulate matter smaller than 2.5 microns (known as PM 2.5).

Before Washington Gov. Jay Inslee’s March 23 “Stay Home, Stay Healthy” order, the state has been monitoring traffic data while considering further restrictions. As early as March 5, drivers traveling at rush-hour in places drove 23% faster on average, suggesting fewer cars on the road. In the first week after the order, highway and ferry traffic dropped significantly.

According to a New York Times review of cellphone location data, the average distance traveled per person per day in Seattle fell from 3.8 miles on Feb. 28, to 61 feet on March 27. The newspaper noted King County had a “100% reduction in mobility” over that time period, making it one of only a handful of counties in the country under stay-at-home orders to achieve this.

A December 2018 Washington State Department of Ecology report found that the transportation sector is the state’s biggest contributor of greenhouse gases, while a June 2018 report from Puget Sound Clean Air Agency found that transportation accounts for 38% of greenhouse gas emissions within the region.

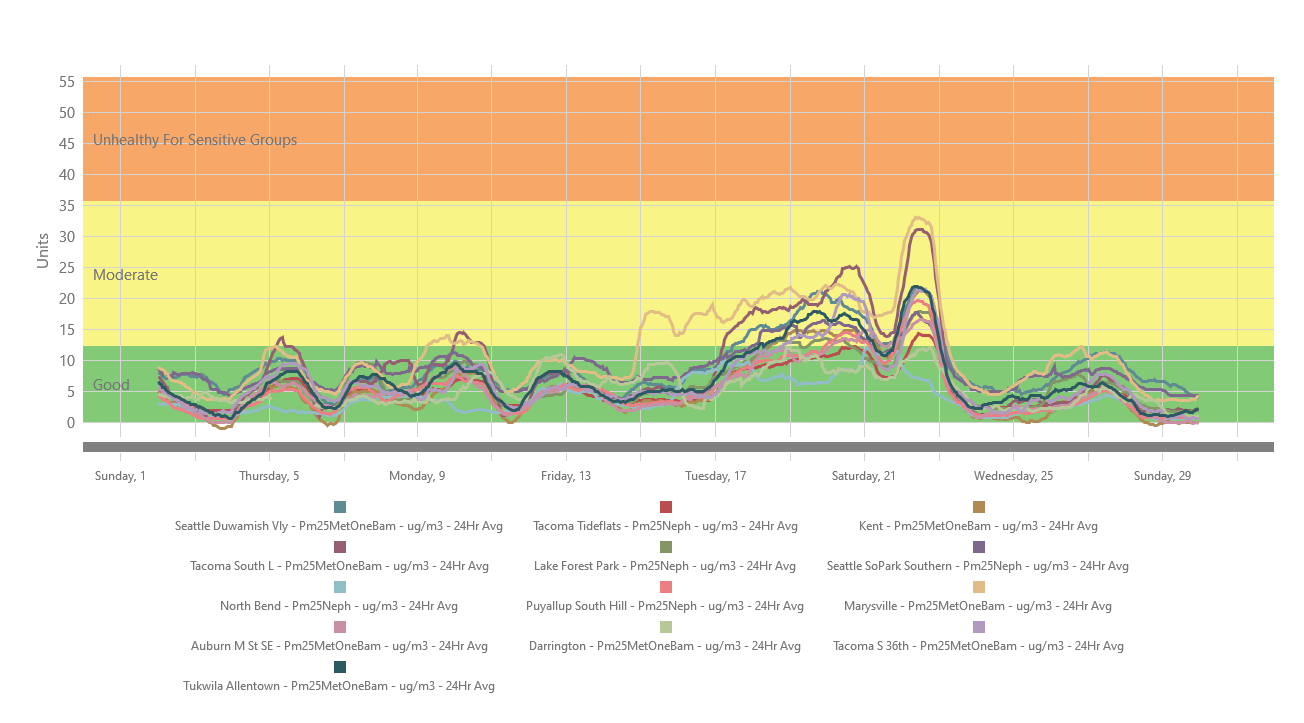

It took a few days for clean air to return to Puget Sound. Inslee’s March 23 “Stay Home, Stay Healthy” order “coincided with meteorological conditions that trapped air pollution at ground level so pollution levels were slightly elevated despite the decrease in traffic,” says UW's Austin. Additionally, the order coincided with an increase in wood smoke as more people stayed home. But “the past week, air quality in our area has [improved]” as weather patterns changed.

Jill Schulte, an air monitoring coordinator with the Department of Ecology, recently compared air pollution levels at the agency’s downtown monitor for the week after Inslee’s March 23 order with five years’ worth of similar periods, according to Andrew Wineke, the department's communications manager for the air quality program. “She saw a noticeable dip in the types of air pollution associated with traffic — nitrogen oxides and carbon monoxide,” he says. “That comes with the proviso that wind and weather have a big effect on those levels, and the last week has been pretty active.”

Erik Saganić, technical analysis manager with the Puget Sound Clean Air Agency, says March started with calm and dry weather that allowed for smoke buildup, but since then it’s been quite wet and windy.

“It is hard to quantify at this stage, with the weather we’ve seen, but it’s safe to say that we’d expect lower emission from vehicles right now with less traffic on the road,” he says. “And, of course, having a viral pandemic isn’t the way we want to see air pollution improve.”

“While all of us want to see less air pollution, this definitely isn’t how we want to achieve it,” Wineke echoes.

Jordan Wildish, a project manager with Tacoma-based nonprofit Earth Economics, started tracking and visualizing global emissions in relation to pandemic-related policies after seeing what was happening in China. The data show a 30% drop in nitrogen dioxide pollution across the U.S. in the two weeks since the World Health Organization’s pandemic declaration, he says, “which is enormous really, kind of unprecedented.” There was also an 18% drop in carbon monoxide.

The improved air quality isn’t groundbreaking in itself, Austin says. We’re seeing concentrations of air pollution that are on the low side, but they're “within the low concentrations that we have seen [before]. Our air quality in Seattle at times is excellent, and that's not only related to our current situation.We need more time to really observe significant change.”

In the long term, it’s unclear what kind of health and climate impacts this period of crisis-spurred low emissions might have.

After past economic downturns, emissions have tended to rebound. In China, emission reductions have faded from 25% below normal to 18% as the country makes progress against the pandemic. Whether these impacts persist, experts say, depends both on how we act now and how we recover. The normalization of teleworking, for instance, could help traffic reductions to persist. But increased home energy use could bring its own downsides.

“[It] depends on policymakers’ responses now and on whether there are any lasting changes in our behavior and priorities,” says Dr. Amy Snover, director of the University of Washington’s Climate Impacts Group. “Once we realize that big, bold, immediate action is possible in the face of one crisis [like COVID-19], might we expect the same in the face of another: climate change?”

Austin thinks the mere experience of cleaner air could connect us all to the bigger issues. Americans know that traffic plays a large role in air quality, but rarely have conditions allowed the public to directly observe that relationship in such drastic contrast.

“In the United States, this is certainly unprecedented,” Austin says. “In a way we can think of this as a natural experiment, where we change our ambient conditions and try to understand how it impacts health.”