Dana Bieber with the No on 1631 campaign called the results a “clear victory for Washington families and small businesses … as well as a victory for the environment.”

The rejection followed a big money opposition campaign that portrayed the initiative as too expensive for consumers and small businesses, unfair and unlikely to produce significant results.

An early October Crosscut/Elway poll offered carbon-fee supporters a ray of hope, showing 50 percent of voters in favor of the initiative and 14 percent undecided. In the final month of the campaign, the opposition ramped up its ad campaign and spending by millions of dollars.

The Yes on 1631 campaign raised an impressive amount of funding — about $15 million— largely from individual donations. But the opposing campaign raised more than twice as much. Funded in large part by the Western States Petroleum Association and other oil industry organizations, No on 1631 accrued more than $31 million, making history as the highest-spending campaign in opposition to an initiative the state has ever seen.

Initiative supporters said the huge spending had an influence on the results. “It’s not hard to buy some confusion with $31 million,” said KC Golden, the chair of environmental organization 350.org. With many voters who were undecided, he said, the ads created uncertainty to “make people back away.”

At the gathering of initiative supporters, early King County returns, showing 57 percent of voters in favor of the initiative, brought cheers. But enthusiasm in the room dwindled as vote counts came in from other counties. Only San Juan and Jefferson counties joined King County in support.

Nick Abraham, communications liaison for Yes on 1631, said many groups supporting the initiative came in expecting not to be fully sure of the results on the first night. He said the coalition of groups that penned the carbon-fee initiative, known as the Alliance for Jobs and Clean Energy, will continue their work against global warming.

“This problem is not going away regardless of whether we come out on top or not,” Abraham says. “It was clear from the beginning that this coalition is not going away either.”

This sentiment was echoed by leaders of organizations like Got Green and the First American Project.

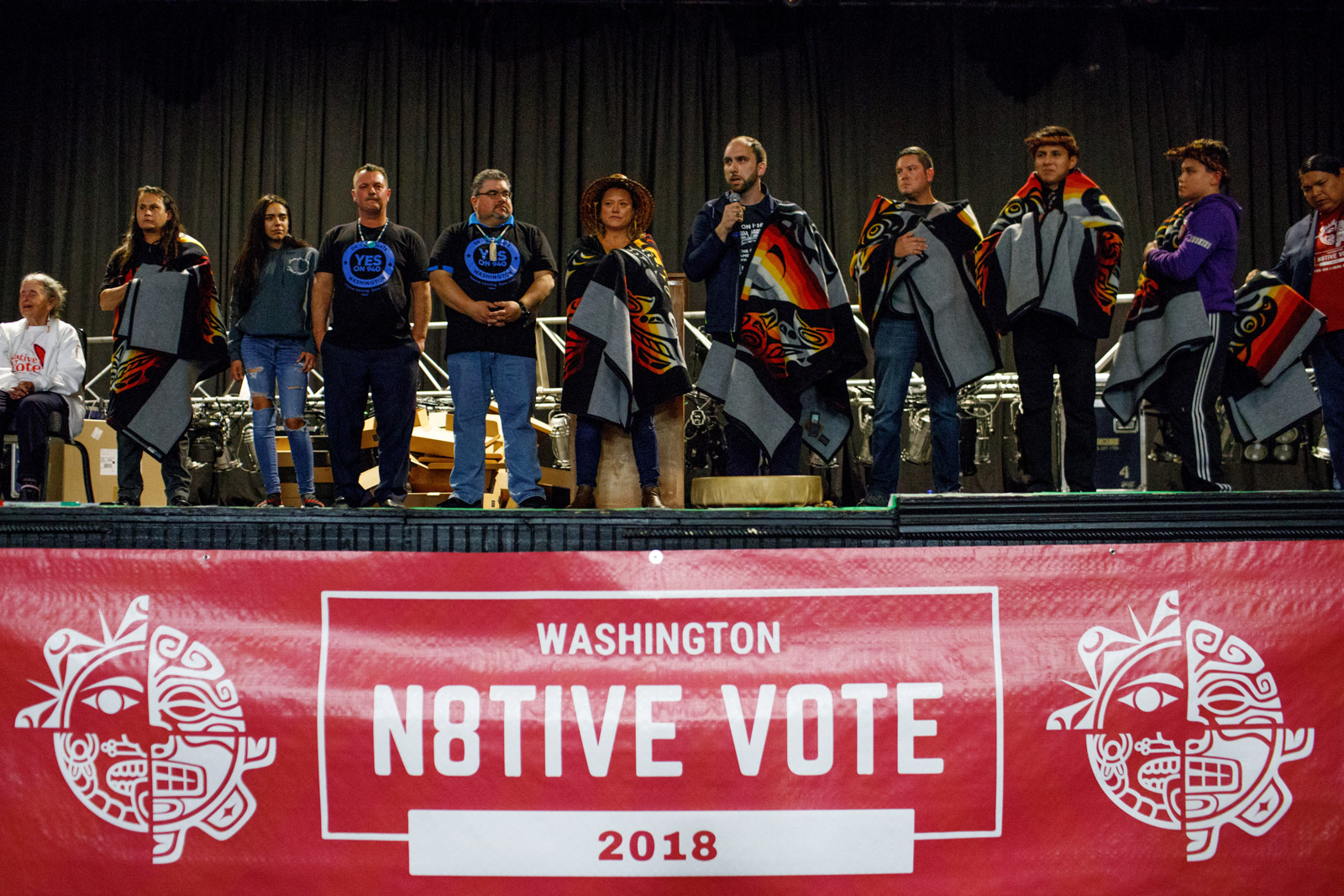

“We’ll be back,” said Quinault President Fawn Sharp, who attended an event held by the Puyallup Tribe at Emerald Queen Casino in support of Initiatives 1631 and 940. “There has to be an outcome where we’re able to restore our natural world and environment, and until we get to that place, we’re going to fight.”

Golden said that this year’s failure will pave the way for a “united political constituency” behind future carbon-cutting legislation, and he expressed hope that future attempts will find a way to succeed despite heavy opposition funding.

Initiative 1631 aimed to be the first measure enacted in the United States to put a cost on carbon emissions by charging emitters. Globally, large countries like Mexico, China and Canada have either introduced carbon-cutting initiatives or made plans to do so.

The initiative promised to do two things: slash carbon emissions by imposing fees on large, corporate carbon emitters and use those funds to promote a greener future. The fee itself would charge $15 per metric ton of carbon beginning in 2020 with a $2 increase each year afterward — or until the state meets its 2035 greenhouse gas reduction goal. The hope is that carbon emissions here could be cut to 36 percent below 2005 levels by reinvesting 70 percent of the fee’s revenue into clean energy. The rest would go to the protection of natural resources and communities impacted by carbon pollution (such as Washington state tribes, who played a large part in the fee’s consultation process).

Although similar proposals like the revenue-neutral 2016 carbon tax have been advanced in Washington previously, the fee’s creation departs from the tradition of its predecessors in a big way. Kickstarted by the Alliance for Jobs and Clean Energy, it roped in diverse communities early on in its writing. This decision has led some groups that have been skeptical of past carbon-cutting attempts to endorse the initiative.

Yoram Bauman, an author of the Washington carbon tax initiative that failed to pass in 2016, said he expects Washington to continue its pursuit of a carbon-cutting initiative. When his carbon tax flopped two years ago, he was told that the state wouldn’t have another chance at a similar initiative for another decade. Initiative 1631 is proof to the contrary.

“We took our swing at the ball and didn’t make it … but somebody else will take that place,” he said.

And because he expects Washingtonians will continue to try to pass carbon-cutting initiatives, Bauman says he has personally advised businesses like the Western States Petroleum Association (who were major funders of the No on 1631 campaign) to create a policy themselves.

“I think there’s a case to be made for the business community in general and the petroleum industry to push for a good policy that they support rather than running the risk of a bad policy that they’re not going to like,” Bauman said. While he doesn’t know of any hard plans on the part of business leaders to work on a carbon-control policy, he said he’s seen interest. After all, he said, even oft-vilified oil giants “live on this planet, too.”

Opposition spokesman Bieber said of the coalition behind No on 1631, “Now that we’ve rejected the measure, we look forward to addressing carbon policy in a meaningful way.”