Artists can be counted on to help us see the issues of our day with new clarity, and in a number of gallery shows currently on view in and around Seattle, they join scientists, journalists and thinkers in documenting, interpreting and expressing ideas about the environmental calamity.

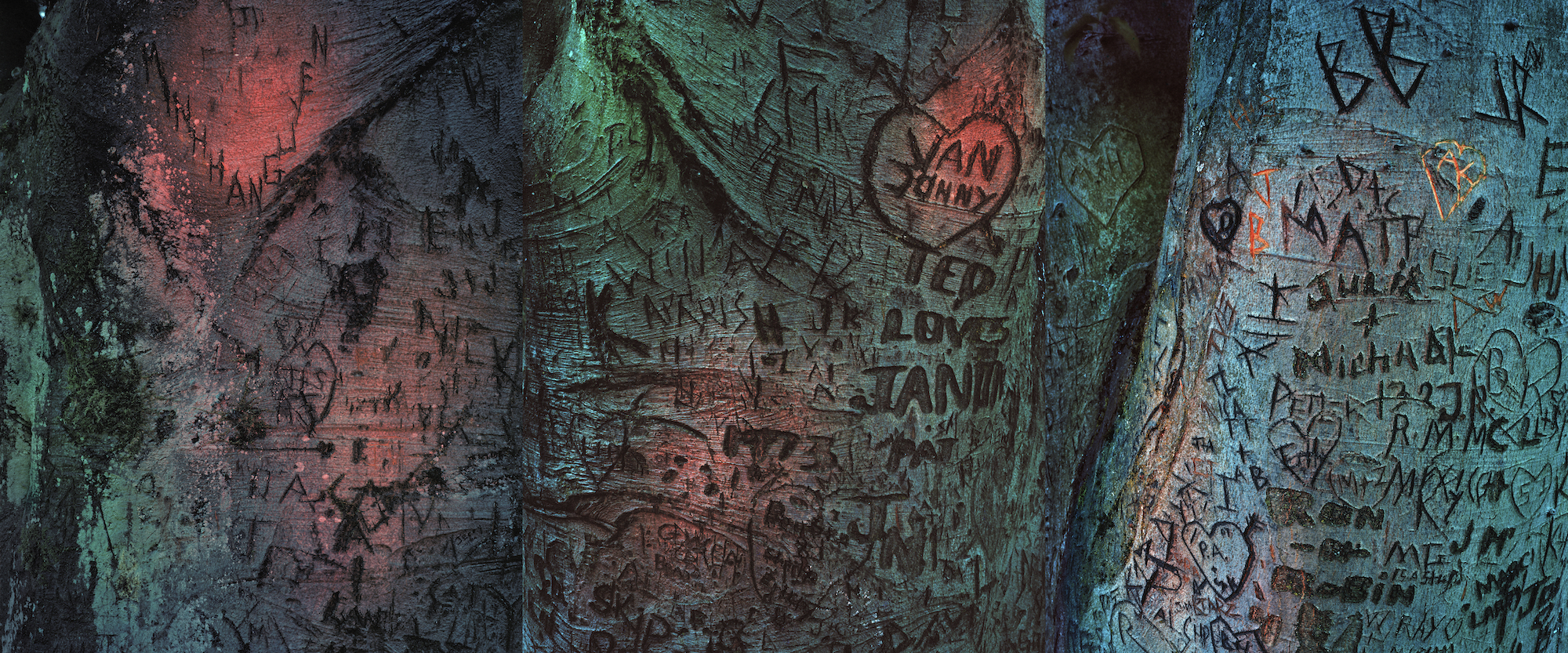

For Pine, at G. Gibson Gallery, Johnson adopted an archaeologist stance, searching the woods around the Puget Sound and Los Angeles for the personal, sometimes perplexing, messages carved into trees. He photographed the carvings at night, over long exposures, using flames, firecrackers and lighting gels for illumination. The process produced unexpected colors and otherworldly glows that give the carvings added significance — as if these were newly discovered cave paintings or underwater wreckage. Presented in large format, the photos look almost 3D, like you could run your fingers across the bark and feel the gashes.

Johnson says the “transgressive act” of tree carving conjures “the most basic desire to declare, ‘I was here.’”

The human impact on nature is also the subject of an expansive new show at the Whatcom Museum in Bellingham. Endangered Species: Artists on the Front Line of Biodiversity features some 60 global artists, contemporary and deceased, who reflect on the state of the planet via painting, photography and sculpture.

The works are alarming and beautiful in equal measure. Artist-biologist Brandon Ballengée shares one of his high-tech scans of amphibians deformed by pollutants. Set against the background of a starry night, the tree frog resembles an alien bearing a message from the future. Ceramic sculptor Courtney Mattison replicates coral reefs at large scale, emphasizing the bleaching that has occurred with rising ocean temperatures, and the abnormal bursts of color seen just before the coral die. Canadian First Nations painter Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun blends surrealism with traditional Northwest formline shapes and symbols. His “Clear Cut to the Last Tree” might sound self-explanatory, but as a history painter, he says, “You don’t always like the subject matter. But someone has to do it.”

In her new show Mapping & Mocking the Anthropocene, at Gallery 4Culture, Seattle artist Kristen Ramirez proves herself a history painter of a different sort — one who uses neon color and all-caps text to explore what she calls “the profound impact of the human hand on our planet.” Graphic illustrations feature abstracted aerial views of crowded city grids plastered with slogans, such as “Habitat Nostalgia,” “The Business of Violence” and “Crisis as the Rule, Not the Exception.” Others reveal a glimmer of hope: “Tenderness and Humility,” “Atrocity and Love.” It feels a bit like a branding campaign gone haywire, one that blares: Welcome to the reality humans have wrought!

Seattle artist Margie Livingston flips the equation, asking the earth to make its mark on her — by way of her artwork. For her recent series, she straps on a harness with a canvas attached and drags it facedown behind her as she traverses various environments, letting the dirt, gravel and bumps determine the image. There is something penitent about this process. The wearing of the harness recalls a hairshirt, a sense of shame and apology.

For her new show, Extreme Landscape Painting, at Greg Kucera Gallery, Livingston added layers of gouache and acrylic to the panels before taking them for long walks outdoors, sometimes on days-long camping trips. As a result of the journey (and the dirt picked up along the way), the paintings have a scratchy visual quality. Peering into them is like trying to make out a voice coming through a bad connection. What is the earth trying to tell us?

Some artists encourage us to listen harder. The hypnotic short science-fiction film Acoustic Ocean, by Swiss video artist Ursula Biemann, depicts an indigenous Sami biologist (played by Sami singer Sofia Jannok) on a quest to immerse herself in audio communications from species inhabiting the deepest oceans. It’s part of the group show Between Bodies at Henry Art Gallery, in which the artists, according to the curators, “question what it means to be human in a time of global climate change.”

In Biemann’s film, the “aquanaut” — decked out in a vivid orange all-weather suit topped by a seal-fur muffler — tosses hydrophonic listening devices into the icy waters off Northern Norway and adjusts complicated technology to better hear the burbles, hums, crackles, chirps of the dark undersea world. Biemann says the film explores the possibility of “rewriting a script for interspecies relations.”

As the aquanaut captures whale songs, subtitles tell us the creatures have memories of their own near-extinction. “They sent a canto of impermanence before diving back down into the deep,” the script says. But of whose impermanence were they singing?

Back at Eirik Johnson’s show, a tree trunk is lit in the palest blue light. The smooth bark has re-grown over three carved words, making them barely discernible, like evaporating skywriting. You can imagine running your fingers across the subtle scar of language, translating it like braille. “We were here,” it reads, a whisper to passersby, a warning from a lost civilization.

Crosscut arts coverage is made possible with support from Shari D. Behnke.