Supporters of the supermajority law say it’s an important check against raising taxes. Washington’s Constitution has required that 60% threshold for bonds since it was amended in 1952.

Because the supermajority law is in the state Constitution, it faces its own hurdles to change – a two-thirds majority vote in both chambers, then voter approval. But this is not unheard of: School levies, which often augment school operating budgets but can also pay for construction and other spending, used to require a supermajority, but now require only a simple majority after the state constitution was amended in 2007.

That 60% threshold for bonds has been a major hurdle to upgrading and repairing schools in many Washington districts.

From 2013 through 2023, Washington voters passed 143 school bond issues. But in that period, another 114 school bonds failed, because though they collected more than 50.1% of the votes, they fell short of 60%, according to the state's Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction figures.

“It creates an unobtainable goal for many communities,” Sen. Sam Hunt, D-Olympia, told lawmakers at a Senate Committee on Early Learning & K-12 Education earlier this year.

But the supermajority still has supporters, saying school districts need to justify their tax increases to voters.

“The answer is not to change the standards, but to build a better case [for a school bond]. I don’t think the answer is to simply change the rules,” said Senate Minority Leader John Braun, R-Centralia.

In most elections, 60% would be considered a landslide. Gov. Jay Inslee’s defeat of his GOP challenger Loren Culp in 2020 was considered a blowout at 56% of the vote. The last presidential candidate who broke 60% in the popular vote was Richard Nixon, who got 61% in 1972.

This session in Olympia, two Democratic pieces of legislation are in play to lower that 60% requirement for school bonds to a simple majority.

Every few years, legislative Democrats try to make this change, but legislation to change the state constitution needs two-thirds approval in both the Senate and House. While supporting the proposed change, Democratic leaders are pessimistic that this will be the year that this passes. Republican legislators are adamant that won’t take place, arguing taxes should be difficult to install.

Washington Superintendent of Public Instruction Chris Reykdal asked Hunt and Rep. Monica Stonier, D-Vancouver, to introduce bills to switch that constitutional requirement back to a simple majority. Reykdal said that he requested the legislation because of the new crop of Republican legislators who were elected to represent their district last November. He hopes that they will see benefits to their home school districts by switching to a simple majority, thus enabling the proposals to pass the two-thirds threshold.

Hunt’s legislation has moved to the Senate Ways & Means Committee, while Stonier’s legislation has stalled in the House Education Committee. Rep. Paul Harris, R-Vancouver, introduced a bill in 2023 and reintroduced it this year to lower the threshold to 55%. That bill has not moved at all.

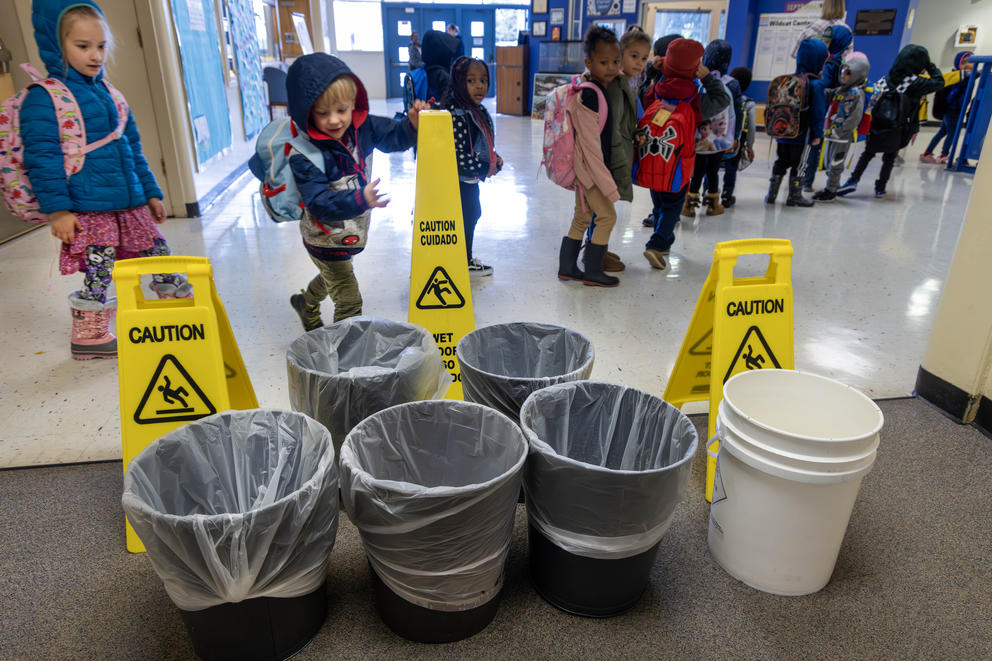

Reykdal said a prosperous school district in a prosperous area can easily find money for repairs and building upgrades. However, districts in poorer areas have problems keeping up with maintenance. “The need is enormous,” Reykdal said.

But even large districts can fail to meet that benchmark. While Tacoma schools have successfully passed its three most recent bond measures, it is still haunted by the specter of a 2007 bond issue that failed despite getting 53% of the vote.

Reykdal said the 60% threshold also prevents local school districts from tapping into state capital-gains-tax revenues marked for school construction and repairs. In 2022, Washington installed a capital gains tax of 7% on such income in excess of $250,000 per person, with the money earmarked for education and school construction.

Between July 1, 2022, and June 30, 2023, the state collected $487.5 million in capital gains taxes, allocating $347.5 million to the school construction account, according to the state Office of Financial Management. The OFM predicts another $290 million will be collected for the school construction account in fiscal 2024. But schools can access those construction funds from the capital gains tax only if local voters pass their construction bonds in the first place.

The capital gains tax is also under attack. Antitax activists have collected enough signatures to put the capital gains tax on the November ballot for a public vote.

“People want to make it difficult to raise taxes,” Sen. Judy Warnick, R-Moses Lake, told lawmakers.

Supermajority supporters say that having a high threshold is important to protect taxpayers, and school districts must instead make better cases to the community that the construction projects are needed.

“Most taxpayers can see a good plan and they can see a bad plan. Sixty percent protects them,” Jeff Daily of Port Orchard, a former South Kitsap School District board member, told legislators earlier this year. Jeff Pack, who says he represents Washington Citizens Against Unfair Taxes, added: “You just want to change the rules to fit your agenda.”

At the same hearing, supporters of the Fife Public Schools discussed their experience with a failed bond. Last November, the Fife district asked its voters to approve a $204.8 million bond for a new $225 million high school. The owner of a $300,000 home would have had to pay an additional $16.75 a month. The vote failed at 2,063 in favor to 1,957 against, or 51.3%.

“We did not pass our bond even though a majority said ‘Yes,’” said Fife School Board member Kimberly Yee. Fife teacher Brady Vallala added: ”The result is that serious repairs won’t happen.”

Correction Feb. 12, 2024: An earlier version of this story misstated the name of the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction.