“As CEO of this organization, finding the staff right now is the thing that keeps me up at night,” said Michelle McDaniel from Crisis Connections. Calls to 988 within King County are routed to Crisis Connections, a nonprofit call center based in Seattle that is one of three centers – alongside Volunteers of America and Frontier Behavioral Health – that provide mobile behavioral crisis services for people across the state.

According to McDaniel, Crisis Connections has experienced a 25%-30% increase in calls since the 988 hotline was implemented last July. With the increase in calls comes an increase in the need for fast, efficient mobile response teams equipped to meet the needs of individuals requiring urgent, in-person care.

State lawmakers are considering a proposal this session to boost funding for the 988 service. House Bill 1134 would add money to the budget to support rapid-response teams, provide more comprehensive training for responders, and put into motion a statewide marketing campaign.

“The bill before you is kind of what are the critical next steps, and I would say the heart and soul of the bill is the rapid-response teams,” Rep. Tina Orwall, D-Kent, the primary sponsor of HB 1134, said at a Jan. 17 hearing.

The measure aims to improve rapid, in-person response standards by establishing an “endorsement system.” Mobile rapid-response crisis teams that are endorsed by the Washington Department of Health would be considered a primary response team. To qualify for an endorsement, teams must meet standards related to response times, training, staffing, and transportation standards. HB 1134 would also establish a grant program to further expand the money available to support rapid-response teams.

In King County, non-emergency follow-up visits currently can take up to six to eight hours, according to McDaniel. With more funding, they hope to improve that response time over two phases. The first phase, which would begin on Jan. 1, 2025, would require endorsed teams to respond to a 988 hotline call within 30 minutes in an urban area, 40 minutes in a suburban area, and 60 minutes in a rural area. The second phase, beginning on Jan. 1, 2027, would improve those times by 10-15 minutes.

About 95% of calls are resolved on the phone, leaving only a small percentage of callers requiring follow-up, including home visits or welfare checks. However, for those who require in-person care, speed is essential if 988 can be a viable alternative to calling 911 and involving law enforcement.

“The No. 1 deep, systemic issue is that we need an alternative number that’s well-serviced to call that has capacity to answer the calls and offer a clinical response, as opposed to a law enforcement response,” said Jennifer Stuber, professor at the UW School of Social Work. Stuber lost her husband to suicide, and has since dedicated her career to creating systems of support for those experiencing mental health crises.

There has been uncertainty as to whether or not calling 988 is a safe option, with Black leaders and mental health advocates across Washington having expressed concern that calling 988 could summon law enforcement.

According to the Washington Department of Health, typically fewer than 2% of 988 calls, texts or chats result in the involvement of law enforcement and/or EMS – for example, if a suicide attempt is in progress and risk cannot be reduced over a call.

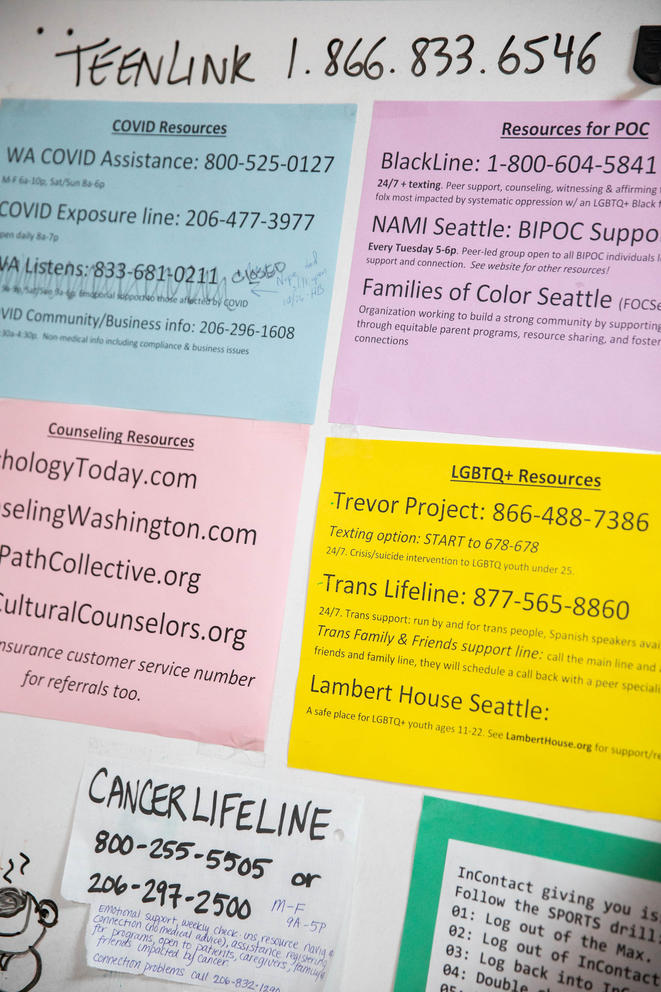

According to the Suicide Prevention Resource Center, the need for culturally competent responders, especially with lived experience, is vital to an efficient crisis response; because of this, Washington became the first state to establish a Native and Strong Lifeline, created by and for Native people.

To reach the Native and Strong lifeline, callers can dial 988, then press 4 to speak with a Native mental health professional.

“Someone who has the same or similar experience as you … [They’ll] be more empathetic, that’s the word,” said Blanca Quiroz, a hotline responder at Crisis Connections, based in Walla Walla. “Because if I were to be in their shoes, I would like to know that someone, in some way, understands what I'm going through.”

Although 988 was launched nationwide, only 13 states had passed legislation ahead of time that would fund its implementation. HB 1477 (from the 2021-22 session), also sponsored by Orwall, created a telecom fee that currently pays for 988 operations.

“The game-changer was not even necessarily that 988 became the simplified number for people to call for crisis intervention and suicide, but the fact that in Washington state, our legislators passed a bill to actually provide a fee on your phones to be able to fund it,” McDaniel said. “That was really the game-changer.”

Before 988 was launched, Crisis Connections was able to answer only about 40% of calls within 30 seconds. After HB 1477 and the implementation of 988, Crisis Connections was able to hire 35 more people and now can answer 90% or more calls within 30 seconds, according to McDaniel.

The fee, which began at 24 cents per phone line and was gradually raised and capped at 40 cents in January, functions like the 911 fee does. According to Orwall, this fee currently brings in approximately $11 million each year.

If Crisis Connections is not able to answer a call, the caller is routed to out-of-state centers. The drawback of this, according to McDaniel, is that responders will not be as familiar with the local resources available to callers.

HB 1134 passed the House unanimously. It currently awaits a hearing in the Health and Long Term Care Senate Committee.

“We’re here to support you and somewhere, somehow, we will help,” Quiroz said. “Don’t be afraid, this line is here for you.”

CORRECTION: Fixes the amount of the 988 phone fee.