But to Michael Simmons, a Cowlitz Indian Tribe member who owns property on the Quinault Indian Nation’s reservation just a few kilometers north, the WDFW officer was mistaken. According to an incident report filed by Branscomb, Michael argued that, because the Quinault nation has a treaty with the U.S. federal government that gives members the right to take up to 50 razor clams per day, and because he was also a member of an Indigenous tribe with property in Quinault territory, he too could take 50 clams a day. That explanation didn’t square with the state officer, and Branscomb cited the Simmonses for fishing without a license and taking more than twice the daily limit. Michael and Andrew were each fined $500. Little could the Simmonses have known that the question of whether they had the right to collect clams, as their ancestors had for millennia before, would spark a legal battle over tribal fishing rights that continues today.

At the core of the dispute is a key distinction between the haves and have-nots: in this case, between Indigenous nations that have a treaty with the U.S. government, like the Quinault, and those that do not, like the Cowlitz. Those treaties, often signed more than a century ago, dictate the rights of tribal members to this day.

The Cowlitz people, said tribal elder Robin Torner during his testimony in the Simmonses’ trial, have been harvesting and eating razor clams from along Copalis Beach long before the United States existed.

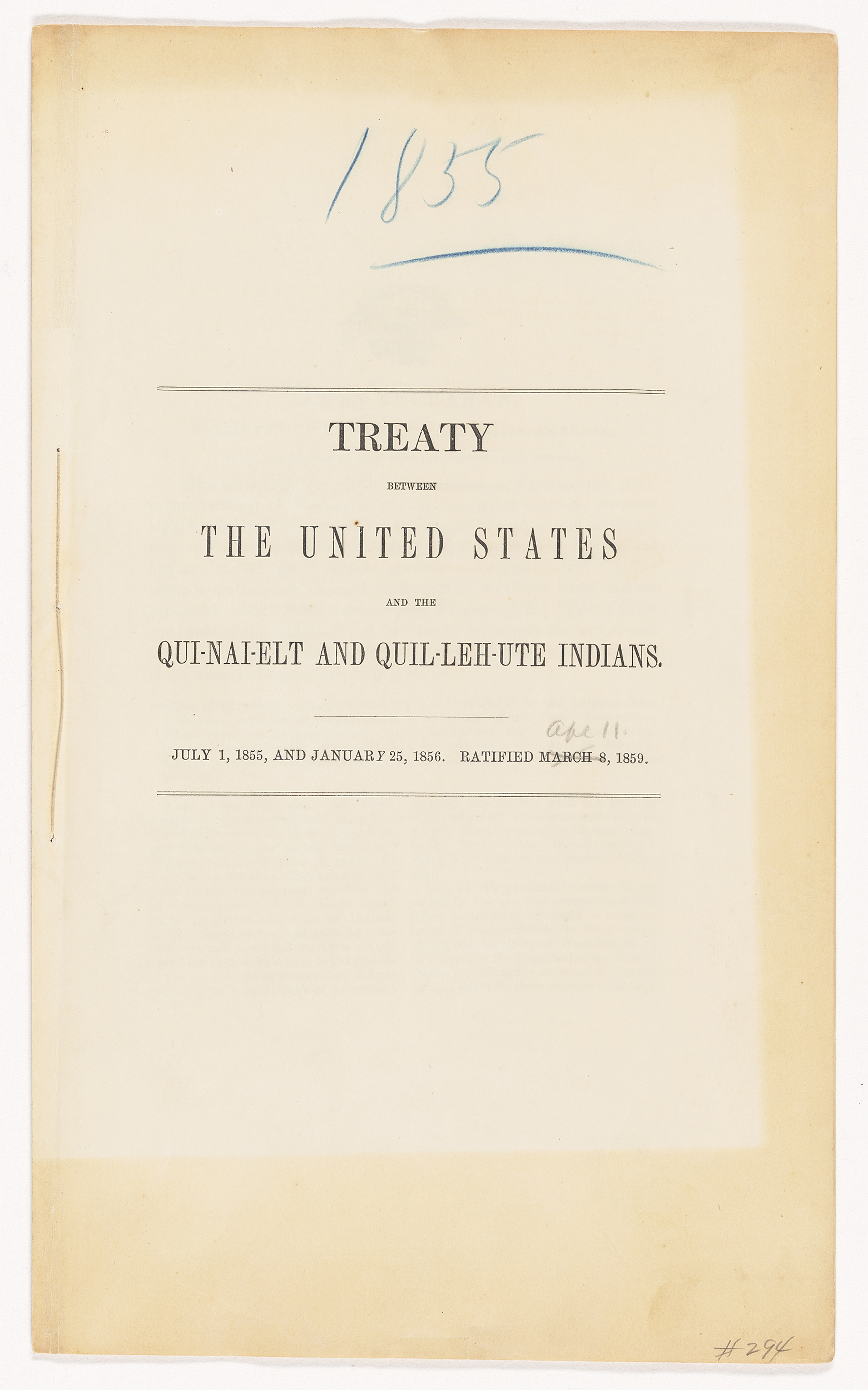

In the mid-19th century, U.S. representatives negotiated treaties with some tribes in the region. These treaties, ratified by the U.S. Senate, relegated tribes to reservations. In exchange, the treaties promised to protect tribes’ existing fishing rights in their usual and accustomed places—including historical fishing grounds off-reservation.

In 1851, the Cowlitz people nearly negotiated a similar treaty with the U.S. government. But the Senate deemed the treaty too generous and refused to ratify it. In 1855, the United States brought forward a new deal: a treaty which would preserve the Cowlitz tribe’s fishing rights in historical places, but mandated that the Cowlitz people move north to a new Quinault reservation. The deal was scorned by the Cowlitz and nearby tribes. “They were like, ‘Oh, hell no, we want to stay in our homelands. We want reservations here.’ And so the treaty fell apart,” says Josh Reid, a University of Washington historian and member of the Snohomish Tribe of Indians.

Then, in 1863, President Abraham Lincoln opened for sale part of the Cowlitz tribe’s ancestral lands. More than a century later, in 1972, a federal court decided that the subsequent rush of settlers onto Cowlitz land terminated the Cowlitz people’s “Aboriginal title”—their right to exclusively use and occupy their homelands.

The Cowlitz Indian Tribe, still without a treaty, went unrecognized by the U.S. government—and without a reservation—until the 21st century.

The mid-1800s saw a wave of treaties signed by the US government and Indigenous tribes in the Pacific Northwest, including the Quinault Indian Nation. But some, like the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, did not sign a treaty. (Photo courtesy of the National Archives, photo no. 187804901)

Today, tribes with a treaty maintain the right to fish their traditional grounds. Tribes that refused to yield, or that held out for a better deal, are limited to fishing on their reservations, if they have one. “In a lot of ways, this was another one of these damned-if-you-do-damned-if-you-don’t type of situations that Native nations oftentimes find themselves,” says Reid.

Dan Lewerenz, an assistant professor of law at the University of North Dakota and a member of the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska who reviewed the appeals court decision, says that, generally speaking, unless a treaty or congressional statute spells out other terms for a tribe, “Indians off the reservation are subject to the same law as non-Indians, so long as that law is exercised in a nondiscriminatory manner.”

For the Simmonses, then, what’s at stake in the case of a few dozen razor clams is their tribe’s right to fish in its traditional grounds off the Cowlitz reservation.

In their appeal, which was heard by the Washington State appeals court this past June, the Simmonses argued that because no treaty or act of U.S. Congress explicitly says otherwise, the Cowlitz people never gave up their longstanding right to gather wild shellfish where they historically did so. And even though a federal court ruled the Cowlitz people lost occupancy rights to their lands in 1863, the Simmonses claim that Cowlitz fishing rights remain separate and intact.

But the court found the argument unconvincing, and in August ruled to uphold the convictions. Essentially, Michael and Andrew and their lawyer were unable to convince the court that occupancy rights and fishing rights are independent of each other, at least in this case, says Lewerenz.

Additionally, the state of Washington argued in its case against the Simmonses that because Congress intended to dissolve the Cowlitz’s Aboriginal rights—including fishing rights—that is the equivalent to them actually being dissolved. The lawyers cited several instances of this intention: first, in 1853, when Congress announced that all tribal lands west of the Cascade mountains, including the Cowlitz’s, would be subject to public sale in 1855 (a year when U.S. government representatives would successfully negotiate treaties with dozens of tribes in the region—but not the Cowlitz); then in 1861, when it set aside funds to move non-treaty tribes, including the Cowlitz, off their ancestral lands. The final blow, according to state prosecutors, was Lincoln’s 1863 proclamation ordering the sale of tribal lands in what is now southwest Washington.

In oral arguments heard in June, state prosecutor William Leraas proposed an analogy: Landlords give notice to renters that they are going to sell the house, and when the landlords put the house on the market, “it’s time to move.” But Ben Cushman, the Simmonses’ attorney, responded that a final step in the analogy is missing — actually giving legal notice that the renters have to move by a certain date. “Here,” he argued, “the walk toward extinguishing the Cowlitz’s rights isn’t enough to extinguish the rights.”

Ultimately, the appeals court agreed with the state, writing that “Congressional intent to extinguish Aboriginal title can be inferred from its actions,” with the key action being Lincoln’s 1863 proclamation that opened Cowlitz lands for sale.

Lewerenz, however, thinks there was a gap in the court’s logic: “There is a Supreme Court case that says that a president, by executive order, cannot extinguish treaty rights,” he says, and therefore it’s reasonable to conclude that a president alone cannot extinguish Aboriginal title either. So when the court wrote in its decision that Lincoln’s executive order ended Cowlitz Aboriginal title, Lewerenz says it didn’t make the case clearly enough that Lincoln’s power to do so stems from the congressional actions it implies were ultimately behind that presidential directive.

This shortcut, according to Lewerenz, seems to continue in Washington a trend begun in earlier federal rulings that makes it easier for Indigenous groups to lose their Aboriginal title.

Over the past century and more, even Indigenous tribes with treaties have struggled to have their rights recognized. At times, many U.S. institutions, including those in Washington, have fought “tooth and nail to prevent even the exercise of treaty rights, which are clearly spelled out in the law and have a long history of being upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court,” says Lewerenz.

“It should come as no surprise,” he adds, “that a right that doesn't have that clear written pedigree is being challenged.”

Ben Cushman, the Simmonses’ attorney, as well as state prosecutor William Leraas, the Cowlitz Tribal Council, and the Quinault Tribal Council did not respond to requests for comment.

This story was produced for Hakai Magazine on Oct. 17, 2022 and is republished here with permission.