The legal issues surrounding disenrollment or dismemberment involve tribal law as well as lawsuits that have been argued in both tribal and U.S. court systems. In most cases, like with the Nooksack Indian Tribe in northwest Washington, power and money, blood quantum, and the sovereignty of each nation all play major roles.

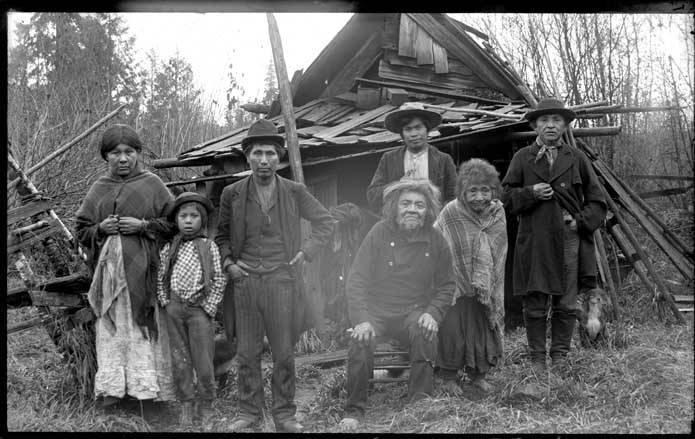

The traditional lands of the Nooksack people once stretched along the Nooksack River and up into southern British Columbia. Bad weather kept them from signing the 1855 Port Gamble Treaty in which area tribes received reservation land. By the 1870s, the Nooksack had lost many members to smallpox and most of their land to settlers. It took until 1973 for the tribe to be recognized by the federal government. In this photo, taken around 1903 by Urban P. Hadley, a group of Nooksack Natives are gathered outside a house somewhere in Whatcom County. Old Tolowie, the man seated in the center, was reputed to be 145 years old at the time. (Courtesy of MOHAI)

Indigenous belonging

The sterile legal language surrounding disenrollment has largely ignored the nuances of traditional Indigenous systems of belonging. The Nooksack 306, a large family group who Nooksack Nation leaders say were erroneously enrolled and are not Nooksack citizens, represent a good example of the way traditional familial landscapes have clashed with the colonial framing of Indigeneity since the turn of the 20th century. While tribal membership may determine employment, financial assistance, health insurance or housing, for these families the issue goes much deeper.

The traditional homelands of the people now known as the Nooksack Indian Nation span what is now northern Washington and southern British Columbia. After political borders were designated in 1846, Matsqui George, Chief of the Nooksack village of Matsqui, remained on the Canadian side and did not obtain a homestead allotment on the U.S. side as other Nooksacks did.

These land allotments, designed by the U.S. government to weaken tribal sovereignty by breaking up tribal lands and families, led to assimilating Native peoples. But they are now one way that many tribes, including the Nooksack, determine citizenship. Since Matsqui chose not to move, the Nooksack tribal council claims his descendants are not Nooksack, they’re Canadian.

Many Nooksack relatives are First Nations and Canadian, and Nooksack and American. They belong to a band in Canada with ties to Nooksack and to the Nooksack tribe in America. In fact, the Nooksack tribe was considered a Canadian tribe until U.S. federal recognition in 1973.

Matsqui’s wife Marie Siamat died in 1875, just days after giving birth to their daughter, Annie George. Matsqui later married Madeline Jobe, another Nooksack tribal member who, the disenrolled claim, adopted Annie George. Annie George then grew up to become the mother of Libby, Louise, and Emma Rose from whom the Nooksack 306 all descend.

For many Indigenous people, adoption is very common and a reflection of traditional kinship systems and relational ways of viewing one another. An imperfect way of understanding this is that cousins are viewed like siblings and your extended community are like cousins, so if a child loses a parent or parents, they have many trusted kin to take on those roles.

Like receiving a land allotment, adoption is another criterion listed in the Nooksack constitution that qualifies a person to be recognized as a member of the Nooksack Indian Nation. The Nooksack tribal council will not recognize the adoption of Annie George and has refused to respond to repeated requests as to why, according to Michelle Roberts, one of the 306 disenrolled Nooksack citizens.

Nooksack leadership did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Map of the traditional Nooksack tribal territory and Indian Reservation. (Courtesy of Demis, www.demis.nl)

Taking sides

“When we were growing up, one thing that all elders would say is that we're all relatives,” said Alex Nicol-Mills. “We're one nation. We're one people. We've always been. We're just living in different places now.” Nicol-Mills has four children and is one of the disenrolled Nooksack 306 citizens facing eviction from their homes on tribal trust lands.

Nicol-Mills has six siblings. The youngest is from his father’s second marriage. That marriage ended just a few months before disenrollment started. The aunt of the youngest sibling from that second marriage was on the tribal council that disenrolled Mills and the rest of the Nooksack 306. “After [disenrollment] happened I just lost connection to all my family on that side, my cousins, my aunties and uncles,” Nicol-Mills said.

According to Nicol-Mills, people felt like they had to take sides, and if you were enrolled and you wanted to support his family, there were repercussions. “If you were enrolled and you didn't take our side, you kind of just fell in line, kept your head down and kept your job,” Nicol-Mills said. “People were scared for their livelihood. I don't blame them for not coming forward. You've got a family to protect, a family to provide for.”

Because of this, Nicol-Mills says he would see family at gatherings and feel like they couldn’t say hi. People who were once close family wouldn’t acknowledge each other in public anymore. “It was so surreal, like walking in the Twilight Zone or walking into a different dimension,” Nicol-Mills said. “The people who they're trying to kick out are their people. I was born and raised and grew up in that [Nooksack] life. I didn't know anything else.”

According to Michelle Roberts, the Nooksack tribal council has refused to meet with them throughout this 10-year process, and each time she submitted documents that prove her family is Nooksack, the council changed the constitution, changed the court rules, and changed the policies and ordinances.

Although the Nooksack council wouldn’t acknowledge the adoption of Annie George by Madeline Jobe, the Nooksack 306 still qualified as Nooksack under what was Section H of the Nooksack constitution, which allowed “persons who possess at least one-quarter Indian blood and who can prove Nooksack ancestry to any degree.”

Blood Quantum

A report by an anthropologist in British Columbia established that Matsqui George was the chief of a Nooksack village in what is now Canada, which would have made the Nooksack 306 eligible for membership under Section H of the Nooksack constitution. Bob Kelly, the chairman who started the disenrollment of the Nooksack 306 in 2012, called for a Nooksack constitutional referendum for the removal of Section H. He succeeded.

Kelly is originally from a First Nations band in Canada and was adopted into the Nooksack Indian Nation.

Blood percentages or blood quantum was introduced as a way to diminish the legal rights of a “mixed-blood” person. Under the Dawes Act of 1887, the federal government denied some mixed-descent Natives land allotments if they had less than one-quarter Native blood, but accepted mixed-descent Native’s signatures if they wanted to sell their land.

By 1912, blood quantum was introduced by the U.S. government to determine who had enough “Indian blood” to be considered for membership, which determined funding for some tribes. It became common after the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act made it legal for Native governments to exist again, but with the strong encouragement of blood-quantum requirements. Now, 70 percent of federally recognized tribes use blood quantum in their enrollment rules, according to the Native Governance Center.

“No matter what, a plastic tribal ID doesn't define who I am as an Indigenous woman,” said Santana Rabang, one of the Nooksack 306. “It's the knowledge that's passed down generation to generation. It's my connection to my land, to my people, to my culture, to my traditions.”

Tribal ID cards are identification cards issued by federally recognized tribes that list a tribal number and may even list official blood quantum, something Mills resentfully likened to the pedigree of dogs and horses. The cards are used to access certain services and can also be used federally like any other ID. In contrast, Ross Cline Sr., who took over as chairman of Nooksack Indian Nation in 2018, seemingly accepted and welcomed the comparison of Indigenous people and blood quantum to that of animals. Asked why disenrolling the Nooksack 306 was so important, Cline told AP News, “If you owned a purebred dog, you’d better understand the question.”

And therein lies another layer of this conflict. Many Indigenous peoples have accepted the colonial metrics of belonging, and for them, things like blood quantum help maintain cultural purity. Many fear that allowing those who do not meet blood-quantum requirements into their nation could erode their culture, traditions and even government if those people were elected.

Rabang was just a teenager when the council began working to remove her family from the Tribe. She grew up Nooksack. When her citizenship was taken from her, she struggled. “It broke me down in a lot of ways,” Rabang said. “[Disenrollment] made me question myself.”

But after the initial shock and grief, Rabang began to speak up and out for herself and her family against blood quantum and disenrollment. “If there was no blood quantum, I wouldn't have to question myself because people would already know who I am and where I come from. I was raised knowing I was Nooksack. My grandma and my grandpa told me I was Nooksack. My parents told me I was Nooksack and I was raised in the Nooksack community.”

Traditionally, “where you come from,” as Rabang said, meaning the sacred land that you call home, that you steward, that your medicines come from, where your ancestors were laid to rest, factors as much into belonging as lineal descent. Lineal descent, as Rabang points out, is your relation to a parent who is recognized as a tribal citizen whether by adoption or birth.

Many nations still use lineal descent, including the Nooksack, but with a caveat of “at least one-fourth degree Indian blood,” which rules out many of the next generation of Indigenous peoples if they marry people who are not Indigenous. “The fact that people are determining before someone is even born whether they belong, while someone is still in the womb rather than raising them in culture, community, traditions, our way of life, motivates me to fight against it,” Rabang said.

Rabang maintains blood quantum is not true sovereignty. “Sovereignty comes by putting people first and ensuring the future for the next seven generations,” Rabang said. “We have the power as sovereign nations, as people who form their own self-government, to change, to deconstruct, and rebuild our constitutional bylaws to reflect more of who we were pre-colonization.

Indigenous rights attorney Gabe Galanda in his Seattle office on Wednesday, July 27, 2022. Galanda has been working with the Nooksack 306, a portion of the tribe who have been battling disenrollment and eviction from tribal housing in a legal battle that questions what human rights are protected by the U.S. government in sovereign indigenous nations that exist in their current form because of U.S. government. (Grant Hindsley/Crosscut)

Sovereign nations

The Nooksack Indian Tribe, just like all other 573 federally recognized nations in the U.S., is a sovereign nation. Just as France has no power to tell the U.S. how to govern, the U.S. cannot tell Indigenous nations how to govern.

But the U.S. federal government has a history of perpetually interfering in Native citizenship requirements through blood quantum as well as census and allotment rolls. “The federal government has always had a say, whenever it's benefited them. They always intervene and interfere in our internal matters,” Wilkins said.

In 1978, a female member of the Santa Clara Pueblo tribe brought a case against her tribe because they allowed only men who married outside the tribe to enroll their children. If a woman married outside their tribe, their children were not eligible for citizenship. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled that interfering in this case would interfere with tribal sovereignty. This case set a precedent for all enrollment cases since.

Wilkins believes this choice by the Supreme Court was also a calculated choice that benefited the federal government. The fewer Indigenous people who are federally recognized as citizens of a nation, the less federal responsibility the U.S. government has to those tribes. This means less financial investment in required supportive services like healthcare through Indian Health Services.

Rabang believes that the way that sovereignty has been used as a weapon against her family is a slap in the face to all the work her ancestors put into fighting for them to become sovereign. Rabang’s great-great-great-great-grandfather, Bih-chy-uh-kaid, participated in the 1855 Treaty of Point Elliott, and his signature is on the treaty. “I am the seventh generation,” Rabang said. “In that moment, he was fighting for me.”

In Washington alone, The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe, the Puyallup Tribe, the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe, the Lummi Nation and the Snoqualmie Indian Tribe have all banished or disenrolled citizens. Banishment, unlike disenrollment, was traditionally used only for the most egregious crimes, like murder, and only after other attempts to restore community harmony, according to Wilkins’ book. Once a person was banished, they had the opportunity to return to their nation if rehabilitation was accepted.

Hope in their hearts

In 2008, similar to the Nooksack disenrollment, a faction of the Snoqualmie council removed and banished elected council members without due process and disenrolled their family members. Unlike with the Nooksack disenrollment, however, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington heard the Snoqualmie citizens' case, ruled that their due-process rights under the Indian Civil Rights Act were violated, and overturned the banishment. Carolyn Lubenau of the Snoqualmie Tribe was one of the citizens who successfully fought her removal from her people's rolls and was later elected as chairwoman.

Many of the Nooksack 306 still hope for eventual reconciliation with the Nooksack Indian Nation. “I still don't hold it against them because it's my family,” Mills said. “I try to do my best to have a good heart and a good spirit. They're always gonna have a place in my heart.”