The differences are stark. In 2020, 85% of King County registered voters cast ballots. In 2021, only 43% of county voters participated in the election.

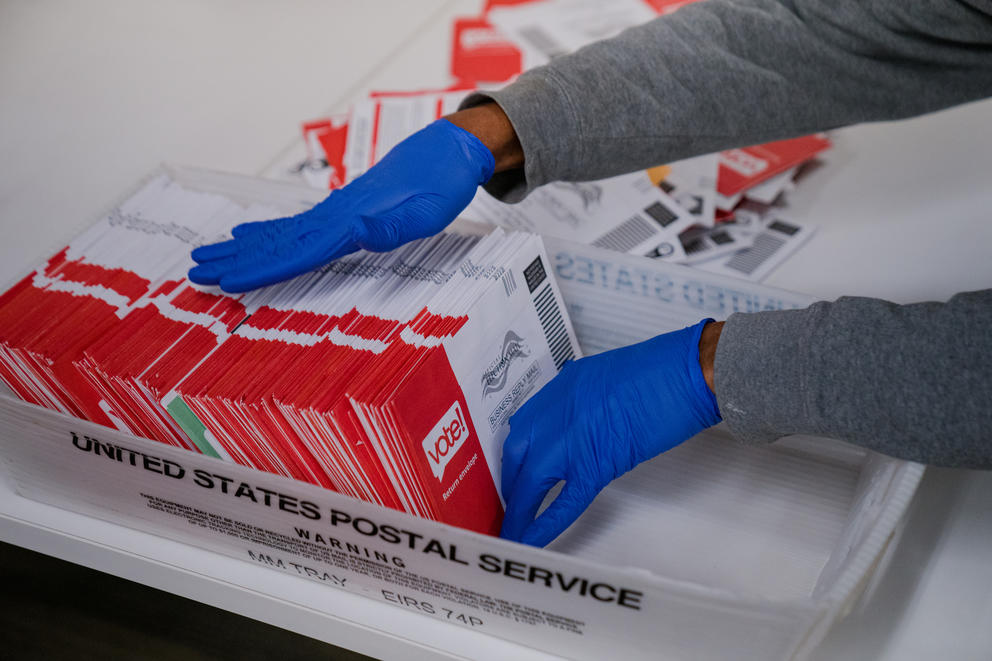

It’s a glaring discrepancy in a state that helped pioneer all-mail elections and has worked to remove barriers to voting through same-day registration, prepaid postage for ballots, convenient drop boxes and the creation of regional voting centers where voters can go with questions or needs.

Now the King County Metropolitan Council is advancing a proposal to move a dozen county races from odd-numbered years to the big-turnout even-numbered years.

The thinking goes like this: Give voters more races to consider when they’re much more likely to show up, and turnout and engagement will skyrocket. Supporters of the proposal also say the boost would help engage communities who face more barriers to voting, like those who speak English as a second language or have disabilities that make it more difficult to cast a ballot.

A council vote is expected Tuesday, according to Council Chair Claudia Balducci. If approved, the proposal – which would amend the county’s charter – would go before voters on the Nov. 8 ballot.

“I would say that the results of elections in even years will be based on far more of our voters, that reflect far more of our demographic populations,” said Balducci, who is sponsoring the proposal.

It’s not a hugely controversial idea. Only three of Washington’s 39 counties elect county officers in odd-numbered years, according to King County Elections Director Julie Wise: King, Snohomish and Whatcom.

Still, the idea has some detractors. A similar statewide proposal by Democratic state lawmakers stalled earlier this year in Olympia, amid questions and criticism.

And in an initial vote on the King County proposal, the nonpartisan council supported it 7-2, with the two councilmembers known as Republicans opposing it.

One of those, Councilmember Reagan Dunn, said local issues that are now debated in odd-numbered years could get lost in the crush of bigger elections. In even-numbered years, Washingtonians, among other choices, might be selecting a president, statewide elected officials like governor and attorney general, and members of the U.S. Congress and the state Legislature.

“The local issues are likely to be lost – things like crime, homelessness, land use,” said Dunn, who is currently running for U.S. Congress in Washington’s Eighth District. “Those things will be buried.”

While Dunn acknowledged the desire to boost voter turnout, he also suggested such plans might ultimately give Democrats another advantage in King County, which has continued to trend more and more progressive.

“I think this hurts, ever so subtly, the Republican Party's chances of winning local office,” he said.

A gradual phase-in

If approved by the council and then voters, King County would ultimately shift elections for all nine councilmember positions, along with county executive, elections director and assessor, to even-numbered years.

It would do that by shaving a year off the four-year positions to be elected in 2023 and 2025, which would reset them for new elections in 2026 and 2028. After those later election cycles, the seats would return to the full four-year terms, according to a legislative analysis of the proposal.

Other local races – like for city mayor and city council, or small government bodies like fire or water districts – would still be held in odd years.

The proposal came to Balducci from the Northwest Progressive Institute, a left-leaning advocacy group based in Redmond.

Andrew Villeneuve, the organization’s founder, earlier this year signed on to support the Democratic proposal at the Legislature.

“If you're going to tell people it's an off-year, why should they vote?” said Villeneuve.

“Why should they care?"

He rejected the argument that the change is being done for partisan advantage.

“This is fundamentally about getting people to vote,” he said. “How healthy is a democracy when 40% are turning out?”

If King County voters approve the change, he said, “I think talking about the cities is the next step.”

Wise, the King County Elections Director, said the shift wouldn’t require huge changes in the way elections are currently conducted. Wise isn’t weighing in on the proposal since her office would count the votes if it goes before voters, she added.

But she did speak earlier this year in favor of the similar statewide proposal.

“I would argue that our odd-year elections are some of the more important elections that shape our community,” said Wise. “But we continue to see across this state, and across the country, if they have those in off or odd years, you see that low turnout.”

The statewide proposal, House Bill 1727, would have eliminated Washington’s statewide general elections in odd-numbered years, according to a legislative analysis. It moved through committee, but stalled without getting a vote in the House.

Sponsored by Rep. Mia Gregerson, D-SeaTac, the bill would limit odd-year elections in Washington to a set of unique circumstances – like elections to recall a public official – or for small government entities, such as public-utility districts or conservation districts.

If approved, it would have also stopped statewide initiatives and referenda in odd-numbered years. That’s a place where conservatives have recently scored election victories, such as the 2019 initiative approving $30 car-tab fees (later ruled unconstitutional by the state Supreme Court). That same year, conservatives also supported a statewide referendum that upheld a longstanding ban on affirmative action in public education, contracting and employment.

But her proposal drew opposition from, among others, a conservative group made up, in part, by first-generation Chinese Americans who organized to uphold that affirmative-action ban.

“We believe HB 1727 violates the WA Constitution by not only stripping away people’s initiative and referendum rights in odd-numbered years, but also limiting people’s legislative power to every two years while allowing the Legislature to continue passing laws every year,” according to testimony by the group WA Asians 4 Equality.

In an interview, Gregerson said she supports the King County proposal, saying putting more elections together makes it easier for people who need more time or assistance to vote. For instance, Gregerson said her uncle is legally blind and needs help with ballots. Other people might need translators, she said.

Earlier in her political career, Gregerson won two elections to the SeaTac City Council before losing in a third bid. And she’s seen firsthand how hard it is to get voters interested in odd-year elections.

“You can run a campaign almost exactly the same, invest the same dollars and the same energy, and you still get just such small turnout,” said Gregerson. “And working people are just like, ‘Which election is this?’”