Washburn had been working largely behind pseudonyms, but, with her federal indictment, she became one of the most outrageous actors in a wartime drama — or farce — a mass public trial involving alleged conspirators, treasonable attitudes, civil liberties and courtroom chaos.

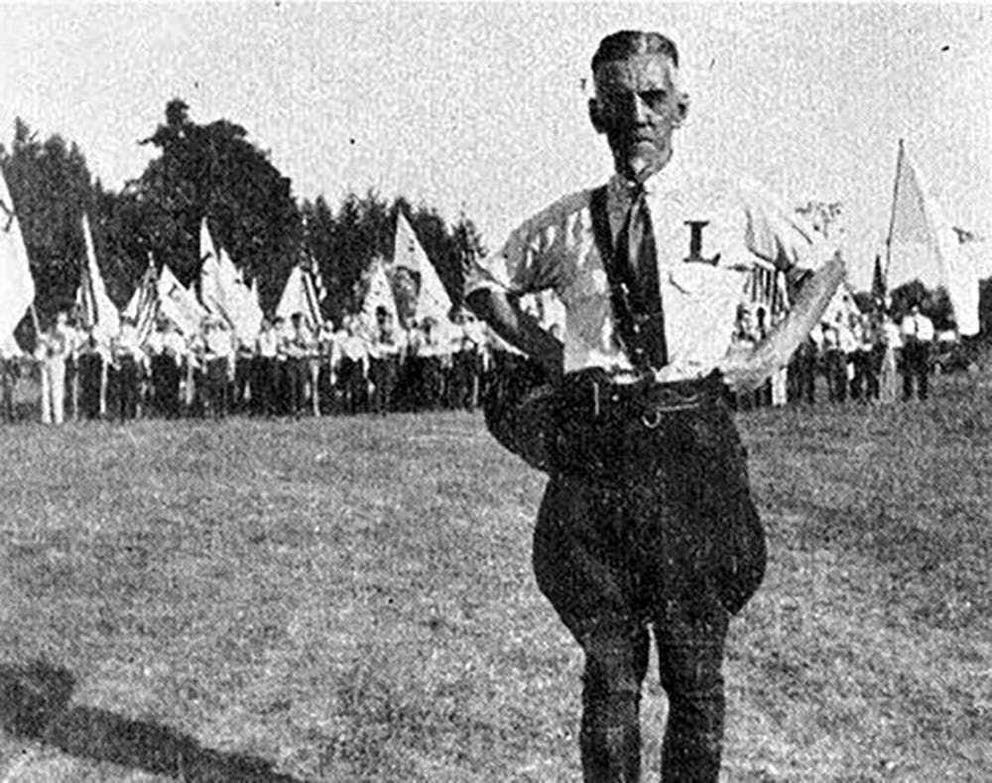

The era leading up to World War II saw a burst of far-right activity and an explosion of hate groups. The German American Bund was openly allied with Hitler, and famous for its 1939 Madison Square Garden rally of 20,000 people. Also in the news was the Silver Legion, or Silver Shirts, a “Christian” fascist group led by a man known as the “American Hitler,” William Dudley Pelley. Its followers were a U.S. paramilitary group inspired by Mussolini’s Black Shirts and the Nazis’ brownshirts.

These and other groups, which openly called for the violent overthrow of the U.S. government, comprised a web of far-right actors who proselytized anti-Semitism, anti-communism and white supremacy, and were propelled by nutty conspiracy theories to try to bring down the elected government, then headed by Franklin D. Roosevelt.

In 1938, an investigator, John C. Metcalfe, reported on right-wing groups for the U.S. House Committee on Un-American Activities, also known, after its chair, Rep. Martin Dies Jr. of Texas, as the Dies Committee. The Dies Committee mostly focused on threats from the left, rooting out communists and later supporting the illegal incarceration of Japanese Americans. But in the late ’30s, as the war approached, there was growing concern about pro-Nazi subversives, and so the committee turned some of its attention to the far right. Metcalfe called out a long list of worrisome groups at a hearing, identifying 135 that were “promoting class, religious and racial hatred.” They included organizations such as America First Inc., a Ku Klux Klan-like group called Knights of the White Camelia, the American Guards, the American Nationalist Party, the Black Legion, American Rangers, the Khaki Shirts of America, the National Socialist Party, American Christian Defenders and the American Aryan Folk Association of Portland, to name but just a few.

The Jan. 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol this year carries strong echoes of this era. Today, a complex of far-right resistance to the elected government is broadly fueled by racism, nationalism and conspiracy theories. Groups range from QAnon to the Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, Three-Percenters and Boogaloo Bois, plus local contingents of militias and neo-Nazis.

The pre-World War II era was also rife with organizations and self-proclaimed movements that wrapped themselves in the American flag, Revolutionary War rhetoric and Christian imagery. They urged a new American revolution in the name of “liberty” and “freedom,” often with a desire for military or authoritarian rule. Trying to upend the results of the 2020 election by force is a case in point.

Hateful hot air from two fascists

In the 1930s, Lois de Lafayette Washburn was what you might call today a dedicated far-right blogger. Her tools were pamphlets and circulars preaching anti-Semitism and screeds against Franklin Roosevelt, plus articles in widely circulated right-wing publications that were widely circulated and often anonymously written. She sometimes used the pen name “TNT” (she compared her ideas and energy to dynamite). She had co-founded the anti-Semitic American Gentile Protective Association of Chicago and sought to provoke radical change in the U.S., peace with Hitler and Japan, and a reckoning with Jews. She and others wanted FDR impeached — it was widely rumored among anti-Semites that the president was a secret Jew, an accusation in line with propaganda from Nazi Germany

In a letter to a supporter, Washburn wrote, “First it is necessary to drag these brigand Jews by the hair of the head … and place them before a firing squad, since death is the penalty for high treason. Then we will proceed to set up William Dudley Pelley’s Christian Commonwealth.” Pelley, who spent WWII in prison for treason, was a vocal anti-Semite who proposed to round up Jews on reservations in his American fascist commonwealth. In 1936, his campaign headquarters, which supported his run for president that year, was based in Seattle.

Washburn insisted she was no Nazi. She claimed to be a great granddaughter of the American Revolutionary war hero, the Frenchman Marquis de Lafayette, and that one “cannot be a loyal, patriotic American citizen without being ‘motivated by a strong nationalistic spirit,’ ” which she asserted was a defining feature of fascism. For her and many others, fascism and Americanism, or as some called it, “Ultra Americanism,” were one and the same.

In Seattle, at the time of her indictment in early 1943, she had been the subject of an FBI investigation into her activities. As she prepared to leave for trial, she told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer that she was calling for a “second Declaration of Independence,” a “reconstruction of the American government and liquidation of existing political parties, labor unions and the military.” Conspiring to undermine the military in time of war was one of the charges against her.

Washburn wasn’t the only person in the Puget Sound area inspired by Pelley. A co-defendant was also a co-conspirator. Washburn had moved from Chicago to the region to be closer to a house painter named Frank W. Clark, a former Silver Shirt who had had a falling out with Pelley. Together, Clark and Washburn created what they called the National Liberty Party out of Clark’s Tacoma apartment, a group dedicated to the overthrow of the government by “reviving the pioneer spirit of 1776.” Their symbol was a rampaging buffalo.

And rampage they did, at least on paper. In his 1943 expose, Under Cover: My Four Years in the Nazi Underworld of America, John Roy Carlson (pen name for Arthur Derounian) devoted much of a chapter entitled “Serpents and Vipers” to Washburn and Clark, whom he met at a semisecret “convention” of a dozen or so “American Quislings” in Boise, Idaho, in July of 1942, post Pearl Harbor. While the Bund and Silver Shirts were basically kaput after Dec. 7, 1941, sympathizers continued to plot and spew.

Clark claimed to have widespread underground contacts with fascists across the country and said he was recruiting stormtroopers among veterans and “German boys” on the West Coast. “I am organizing patriotic bands in the Northwest,” he told Carlson. “The revolution has got to get going in the West first.”

“Clark was one of the most bloodthirsty Turks I have ever met in my work as an investigator,” Carlson wrote. “He talked incessantly of massacre and murder and pogroms.” Clark said he wanted to be made “chief executioner of those guys who are now sticking up for Democracy.”

Most of what Clark and Washburn were selling was hateful hot air. The war had forced many far right and Nazi sympathizers underground, with the FBI and others investigating possible ties to the Axis powers. The sympathizers’ rhetoric was extreme, but no vast armies of stormtroopers appeared out of the Northwest’s woods to launch a revolution during the war.

A carousel of crazy

The Smith Act of 1940 made it not only illegal to act to overthrow the government, but outlawed advocating such a thing in print or forming groups with such an intent. In other words, hot air could be illegal, especially so if it undermined the war effort or was in league with an enemy. In 1942 and again in 1943, government indictments came down. Some 30 defendants were prosecuted in a mass sedition trial in Washington, D.C., Washburn and Clark among them.

A highly publicized legal wrangling ensued. It turned into a complicated, drawn-out mess, the mass trial of so many individuals proving unwieldy. Washburn and Clark’s co-defendants were largely cut from the same cloth — a kind of clown car of extremists and their lawyers.

Attorneys objected to everything from procedures to testimony to whether the trial should be held in wartime at all — the war itself deemed prejudicial to jurors. The trial was interrupted by the defendants’ political speeches, jeering and acting out. It was argued that Hitler and Hermann Göring, one of the most powerful figures in the Nazi party, should be called to testify, while others argued against that idea. One defendant died, another went on the lam, but was later caught near Canada. Some moved for separate trials. And some argued, producing echoes we hear today, that the showcase trial was an unconstitutional attack on the First Amendment — and many civil libertarians agreed. The judge held various people in contempt, gave out fines and tried to maintain order. The trial, a carousel of crazy, dragged on throughout 1944.

No one acted out more than Lois de Lafayette Washburn. During a pretrial hearing she came to court wearing her nightie — she said jail guards had stolen her clothes — and demanded a typewriter. On another day she swept into the court and, after her name was called, announced, “Lafayette, we are here to defend what you gave us: our freedom from tyranny.” She insisted that prospective Black or Jewish jurors be dismissed, and they were. She was known for frequent outbursts. She was said to convulse in “hysterical” laughter at inappropriate times.

Washburn gave the Nazi salute, shouting “I’m a fascist,” and thumbed her nose at the courthouse in front of the media, according to historian Glen Jeansonne, in his book, Women of the Far Right. She later said she was just giving the press what they wanted. After those antics, her fellow sedition defendants wanted to keep their distance. One requested the court give her a lunacy test.

While some questioned her mental health, her antics could also been seen as a kind of subversive guerilla theater, not unlike those performed in more modern political trials like that of the Chicago 7 in the 1960s.

After eight long months, the judge died of a heart attack and a mistrial was declared. The Allies won the war in 1945, and the sedition case was dismissed a year later. An analysis in the University of Chicago Law Review in 1984, dubbed the trial a “fiasco.” The government had nothing to show for its efforts beyond keeping some of the era’s most radical haters out of commission for the duration of the war.

Historian Jeansonne wrote of the case: “There was little question that the prosecutors had shown the defendants to be despicable characters, some of whom may have committed the acts of which they were accused. The defendants nevertheless did not conspire as a group or with Hitler. They were mainly minor bigots who would not have known what to do if a revolution had occurred.”

Washburn faded from the record soon after. She was spotted by Carlson in 1945 doing secretarial work for a conservative U.S. senator. She continued to write articles into the 1950s for the anti-communist press, even as her health failed and her organizing ceased. But the movement she was part of in the 1930s and ’40s endures. It has moved from the era of the mimeograph machine to the age of social media and dark web chat rooms. One can easily imagine Washburn taking selfies in the Capitol rotunda wrapped in a Don’t Tread on Me flag. Far-right insurrectionists carry on today in ways Washburn would undoubtedly salute.