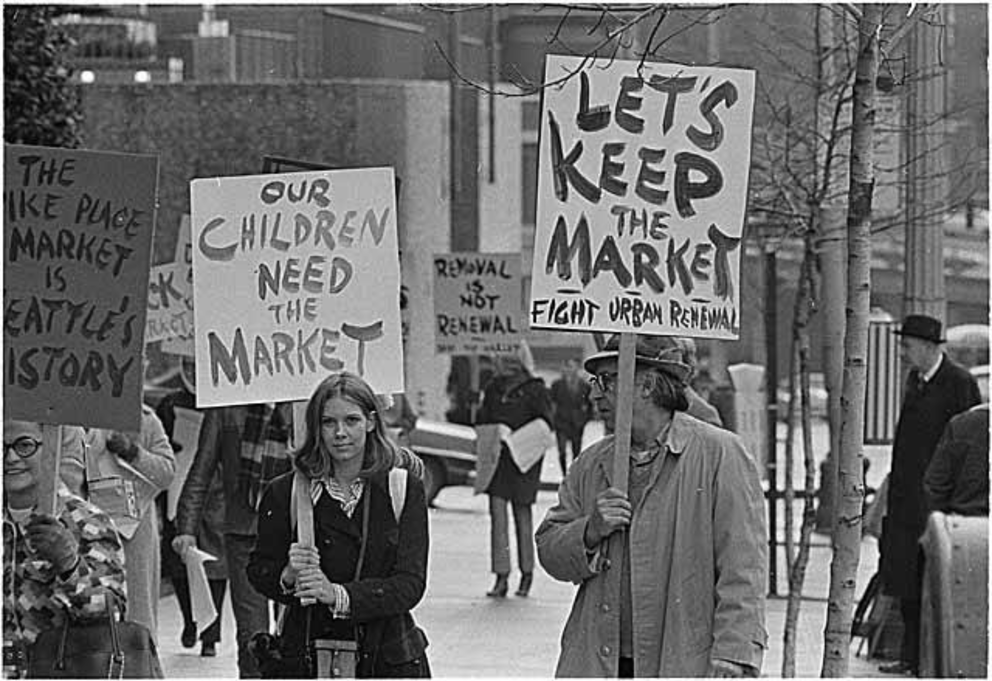

It was the vote to “save” Pike Place Market and create a 7-acre historic district that had been slated for massive “urban renewal.” A number of concepts were in play for the aging public market, which was born in 1907.

The market came about as a kind of protest against the waterfront produce warehouses that were gouging local farmers and consumers. The growing city needed better and more affordable food options. The farmers needed to make a living by selling direct. Creating a public market for farm-to-consumer transactions was a win-win.

It had a lot of local character, noted by writers like Allen Ginsburg and the Beats, who were drawn to skid road, and Northwest modern artists like Mark Tobey, who were inspired by the market's color and energy. But as the market aged, there was a growing drumbeat in Seattle to replace it, modernize it, bulldoze it.

It was the era of chain supermarkets with big parking lots, a time when many businesses, workers, and shoppers were migrating to the suburbs and shopping malls like those in Bellevue and Northgate. Seattle, planners argued, needed more freeways and should “renew” the market by keeping only a little more than an acre of it while building high-rises, offices and parking garages, and putting “more respectable” stores in its place.

Seattle needed to fend off blight, they said. Plus, the makeover would mean jobs for a city wracked by the Boeing recession. The market — multileveled, multiracial, multifaceted — was an aging antique. Such markets were shutting down all over the country. The federal government's Department of Housing and Urban Development had millions of dollars in grant money it could send to Seattle for the “renewal.”

In retrospect, it seems like a no-brainer to preserve Pike Place Market, given what a treasure and downtown economic engine it has become, serving tourists, cruise shippers and a growing population of downtown residents. Farmers markets have seen a renaissance and are now fixtures in nearly every neighborhood. But it was not obvious to many people in the early ’70s as Seattle dealt with recession and downtown, once again, needed “saving.”

The powers that be favored saving a crumb and giving it a massive modern makeover. A citizen’s group, Friends of the Market, coalesced to not only oppose “renewal,” but came up with a counterproposal, which would be put to a public vote, to create a 17-acre historic district and let the public control its future; upgrade the market, but leave its character intact; buy properties and rehab them instead of tearing them down. The goal wasn’t just to save fruit and craft stalls, but to protect a neighborhood of low-income downtown residents and preserve the farm-to-table food chain.

I recently purchased tickets to and attended a Friends of the Market fundraiser in late September to mark the market’s rescue 50 years ago. Many of the original Friends who campaigned in ’71 are still around, and the group has been a persistent supporter and watchdog of the market for the past half-century.

The event, held in the market atrium, set the stage for celebrating the anniversary of the public vote that saved it. Tables at the event featured artifacts of the fight: campaign handouts listing the names of supporters, old campaign buttons. I picked up one that was mottled with brown moisture spots, suggesting it had been worn by picketers or signature gatherers in the rain. “Let’s Keep the Pike Place Farmers,” it said in hand-done script that was a signature of the campaign’s leader and most passionate advocate, architect Victor Steinbrueck.

Steinbrueck, a University of Washington professor, was outspoken in arguing to preserve urban character. He was instrumental in establishing Pioneer Square’s historic district a year earlier. Then he helped catalyze public opinion for the market. Steinbrueck was also an artist who had helped capture the city’s urban character in his black-and-white sketchbooks. Seattle Cityscape in 1962 revealed the city’s urban layers in a way most people hadn’t seen; he did the same for the market with his Market Sketchbook in 1968.

Steinbrueck's voice carried weight in historic preservation, but he wasn’t all about the past. He had designed the Space Needle’s tower for John Graham Jr. He was tough and acerbic in his crusades. In “nice” Seattle he wasn’t afraid to pick fights or make enemies. His son, Peter Steinbrueck, who also worked on the Friends campaign as a boy, has said that there were families in his neighborhood who would not let their kids play with Peter because of his father, a thorn in the side of the so-called establishment.

The proponents of redevelopment argued it was necessary for downtown, the city had a shovel-ready plan in place, and HUD was prepared to give the city over $10.6 million for the effort. That money would be jeopardized, it was argued, if the Friends scheme was victorious. Nonsense, Steinbrueck argued. Their plan was better for the city, the market and the vendors, and Seattle would still get the money to rehab the new historic district.

While the campaign relied on grassroots, it was able to take out newspaper ads to rebut opponents. Some national coverage of the fight raised awareness of the stakes, too. The Washington Post’s architecture critic, Wolf Von Eckardt, wrote: “What is at stake is tradition, a meeting place, a place where many people spend the day, an urban experience.”

Surprisingly, they were able to raise money to place ads on Seattle’s three big TV stations, KING, KIRO and KOMO. Steinbrueck asked Barbara Stenson, a well-regarded KING-TV reporter — on a break from journalism at the time — to create an ad for the Friends initiative. She did. He insisted on paying her with a Mark Tobey lithograph, she says. She got her husband, Al Stenson, to shoot the film, and the money to run the ad on the local stations was raised by a bank loan against Mark Tobey artworks that had been donated to the Friends of the Market.

Stenson says Mayor Wes Uhlman, an opponent of the Friends initiative, was furious with her on election night as the returns showed the market plan passing readily. “He chewed me out colorfully and vividly,” she remembers. On Nov. 3, 1971, the city awoke to discover that the vote to protect the old market had won by a solid majority of 20,000 votes over the opposition. To his credit, she adds, Uhlman pivoted virtually overnight and worked to implement the plan, given its popularity with the voters.

Seattle Times reporter Dick Larsen found Steinbrueck at the market’s Athenian restaurant having a morning-after breakfast of French toast. Recounting the fight for the market, Steinbrueck told Larsen how market activists had been rebuffed by the city council time after time. “We lost every step of the way. But we never lost so badly that we couldn’t see our way out of it.” The front page headline on the story read, “Jubilation amid vegetables: ‘A real place in a phony time.’ ” The quote was Steinbrueck’s.

Steinbrueck would perhaps find our times as “phony” as ever, but the market remains an authentic, valued urban community. Plans for a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the vote are set for Oct. 23, with an all-day event at the market featuring public screenings of a new documentary, Labor of Love: Saving the Pike Place Market, history tours and a treasure hunt.

“Saving the market” is an ongoing effort. It has been recovering from the pandemic — business rebounded well during the summer, but how it will fare this winter is unknown. The challenges for the market community won’t disappear overnight.

The Market Foundation is looking to launch an endowment campaign next year to look at “long-term” stability for the market community — the people who work, live and are served by it, says the foundation’s community relations manager, Patricia Gray. A “recovery campaign” to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on the market community in 2020 was successful.

Mary Bacarella, executive director of the Pike Place Market Preservation and Development Authority, says the challenges the market has faced during the COVID-19 pandemic make this a perfect time for the 50th anniversary. “The Friends gave us a blueprint for saving the market,” she says, and the Authority has drawn on that during the pandemic. It has helped them navigate the challenges; it has renewed the community’s reliance on each other, reminded people of the need to take care of one another.

The market, she believes, reflects the soul of the city. “The Friends,” she says, “saw it as a place for them to go to experience what the city is truly about.” A place of respite, or to immerse themselves for a bit in what matters most. The folks who “saved” the market designed a community that reflects all the diversity and dynamism of a rich, multilayered urban environment. It wasn’t the obstacle to modern Seattle and downtown, it is a role model and has been a savior.

The Friends and their supporters preserved it; they grew it, they continue to shape it as the city grows. It’s not static, but it is still a touchstone of Seattle’s urban essence, with all the features we say we want: diversity, density, caring, color and vibrancy, infused with localness and personalities. Those who have stewarded it through the past half century can be pleased to have done so well and are hopeful for the future. Pike Place Market wasn’t saved to protect the past, but to guide us into the future. “This is who we are,” says Bacarella. And who we want to be.

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated that the 1971 voter initiative created a 22-acre historic district. The size of the district created was 7 acres. The protections were extended to 22 acres at a later date.