Gov. Inslee has yet to announce whether and in what form he’ll extend Washington state’s eviction moratorium beyond the end of this month when it is due to expire. But in the meantime, the cities of Kenmore, Kirkland and Seattle have all extended local moratoriums through Sept. 30, and Seattle and Kenmore have both passed additional measures to prevent evictions for pandemic rental debt after the moratoriums end.

But lawmakers and renter advocates aren’t stopping there. Recognizing long-standing and inherent asymmetries of power in the landlord-tenant relationship, as well as the dire human, social and public health costs of eviction, they’re using the urgency of this moment to advance new permanent protections, too. [Disclosure: I am personally involved in this work through the Transit Riders Union and the Stay Housed Stay Healthy coalition.]

Last fall, the city of Auburn capped late fees at $10 per month, mandated four months’ notice of substantial rent increases and adopted a “just cause” eviction law that protects renters from being kicked out of their homes without a good reason. Earlier this year, the Legislature passed a more limited statewide just cause law, and the Legislature and the city of Seattle both passed “right to counsel” laws that will help renters obtain legal assistance during the eviction process. Seattle expanded its just cause law to cover all lease types and prohibited evictions of families and educators during the school year.

This is the first in a series on the housing rental market. Read Parts 2 and 3.

Now, the King County Council is considering permanent renter protections for unincorporated areas of the county such as Skyway and White Center. The package includes a strong just cause law, caps on move-in fees and late fees, three to four months’ notice of substantial rent increases, a ban on requiring Ssocial Security numbers for tenant screening and more.

Not everyone is happy about this flurry of activity. Landlord groups like the Rental Housing Association are lobbying elected officials and mobilizing their members to speak out against these proposals, sometimes playing fast and loose with the truth. But one of their arguments deserves a closer look.

Cory Brewer, RHA board member and vice president of residential operations at Windermere Property Management/Lori Gill & Associates, recently argued in The Seattle Times that renter protections cause “erosion of the single-family rental-house supply,” which he says is “disappearing right out from under us.” A few days later, the Seattle Times Editorial Board followed up with its own piece on the same theme, urging Mayor Jenny Durkan to veto several aforementioned Seattle measures “to preserve housing supply.” (Durkan returned the legislation to the council unsigned last week, which means it goes into law without her enthusiastic blessing.)

Their basic argument is that small “mom and pop” landlords just can’t deal with all the rules and regulations, so they get out of the business. Their properties become owner-occupied houses or are torn down for redevelopment. Renter households — Brewer points especially to lower-income families too large to fit into a two-bedroom apartment — are left high and dry.

If renter protections truly reduce housing options for renters, that might indeed be cause for concern. But is it true?

Neither op-ed contains a shred of evidence that renter protections affect rental housing supply in the aggregate. The only thing resembling data are some numbers Brewer provides from his firm, which I’ll get to later. Both pieces confusingly conflate permanent renter protections with COVID emergency measures; I will try to disentangle these two very different threads.

So what does the evidence actually say? Studies are sparse, but one can look at trends in rental housing stock before and after renter protections are implemented. Tim Thomas, research director of the Urban Displacement Project at University of California Berkeley, did just that for Seattle and New Jersey, which first adopted just cause laws in 1980 and 1975, respectively. He found no discernable effect. Meanwhile, there is evidence that these policies work as intended; a recent review of the literature on anti-displacement strategies and their effectiveness identified just cause and right to counsel laws as having high potential to prevent displacement.

There’s a lot more research on rent control, which has been in place as an emergency measure since the start of the pandemic and which Seattle Councilmember Kshama Sawant has long called for, although it’s currently prohibited by state law. Here the evidence of effects on housing supply is mixed, which makes sense since rent control policies are many and varied. But, as I’ve written before, scholars are increasingly concluding that well-designed rent regulations can promote neighborhood stability without decreasing housing production or supply. In jurisdictions where rent control has often been blamed for housing shortages, like San Francisco, there are more obvious culprits in the mix, like highly restrictive zoning laws.

Thomas says that even when renter protection laws appear to correlate with rising sales of single-family rental properties, there are larger forces at work. Such laws are usually proposed in hot housing markets that are already experiencing gentrification.

“Homes are too expensive, so mom-and-pops that are retiring are more likely to sell to a developer because new potential mom-and-pop landlords can’t afford buildings,” says Thomas. “Just cause is the simple blame, but there’s no evidence of it forcing landlords to sell. The real reasons are more complex and people don’t want to touch it.”

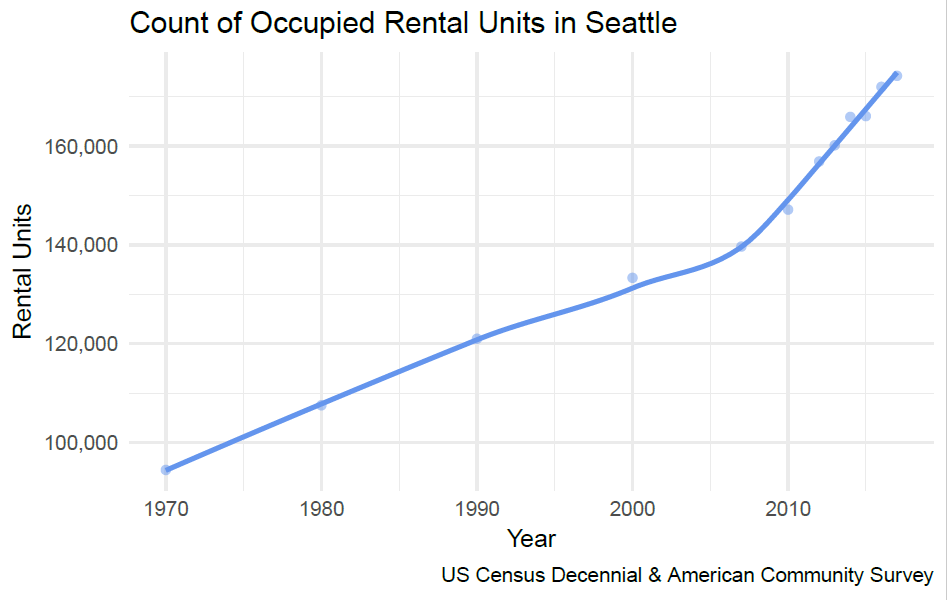

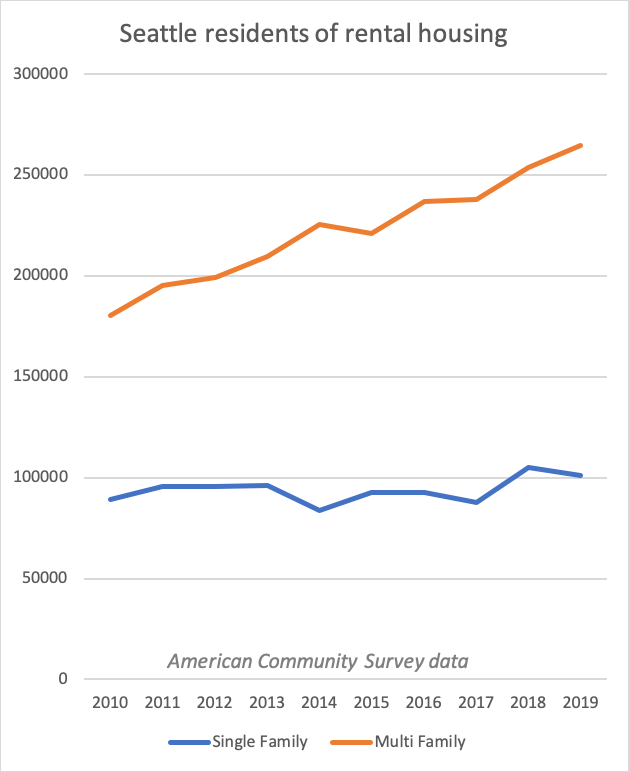

That said, pre-pandemic at least, it’s not obvious that “mom and pop” landlords in Seattle and King County were abandoning the market in droves due to renter protections or any other reason. Data from the American Community Survey indicates that the number of people living in single-family rental housing in Seattle and King County has stayed relatively flat over the past decade, while multifamily rental housing has expanded steadily. Seattle adopted a number of new rental regulations in this period, including in 2012, 2015, 2016 and 2016 again, and 2019. If some single-family homes were leaving the rental market, they were evidently being replaced by others.

That brings us to the pandemic, and to Brewer’s numbers: “Windermere Property Management/Lori Gill & Associates saw a 48% increase from 2019 to 2020 in clients selling off rental homes, and a poll of the agency’s remaining clients this January found 35% of the property owners who were looking to sell were doing so because of new regulations.”

Brewer at least admits that his sample size is small; The Seattle Times editorial board just repeats his percentages and states that landlords are fleeing the market as though it were an established fact.

I asked Brewer for the actual figures. He told me that 52 of his firm’s Seattle clients sold their rental homes in 2020, up from 35 the year before. In their entire portfolio, which covers King and Snohomish counties, sales went from 100 to 133, or an increase of 33%.

Of Windermere’s 1,600-plus clients throughout the region, says Brewer, over 80 indicated in the January poll that they expected to sell this year, with 35% of them pointing to “new legal regulation” as the reason why. That’s about 28 clients, or 1.75% of the total pool.

Let’s assume, despite the small sample, that Windermere’s numbers do reflect the entire single-family rental market, including the many small landlords that don’t use a property management firm. If 2020 had been a normal year, and if we had reason to believe that these extra sales meant an overall dwindling of rental stock, or at least homes for larger families, this might be cause for concern.

But 2020 was not a normal year. There was and is, you might recall, a deadly global pandemic and unprecedented economic dislocation. Governments, businesses, households, all of us have had to make tough decisions, weighing bad consequences against worse. No doubt unpaid rent and eviction moratoriums have strained many small landlords. It’s entirely believable that this contributed to a jump in 2020 sales. It’s also believable that in January 2021, 10 months in and near the peak of coronavirus deaths, 1.75% of “mom and pop” landlords were facing enough financial disturbance to consider selling this year. (The permanent renter protections Brewer opposes had not even been proposed in January, so it’s hard to imagine “new legal regulation” referring to anything but the eviction moratoriums and temporary ban on rent hikes.)

If all this causes a downward blip in single-family homes for rent, that might be unfortunate, but this consequence must be weighed against the human consequences of lifting moratoriums prematurely. Given that King County’s main rental assistance program won’t begin writing checks until mid-July, I think it’s pretty clear that the policymakers choosing to protect renters from COVID debt evictions are making the right call.

Extraordinary pandemic sales are certainly no argument against permanent renter protections. If lawmakers want ample, affordable rental housing, they have many policy options at their disposal, from zoning reform to stepping up investment in public, nonprofit and community-run housing. In fact, it’s not at all clear that maintaining single-family rental stock operated by small landlords should be a policy goal at all — I’ll dig into that question more next week.

Watering down or failing to pass laws that protect vulnerable renters against eviction and homelessness is not the right way to “preserve housing supply.” Landlord lobbyists and The Seattle Times editorial board want you to believe that renter protections are bad for renters. Don’t buy it.