Arcana recalls this story while sitting on a frigid bench outside a restaurant in her Portland neighborhood, a bright blue sculpture of a bicycle across the street matching her tiny round glasses. She arrived in the Pacific Northwest nearly three decades ago, bringing memories of a very different time. Reflecting on the youngest people Jane served comes naturally for the woman who taught high school coursework in English, creative writing and the humanities before she became, as she puts it, “an underground abortionist.”

“It probably is because I spent all those times with the teenagers,” she says, fitting together the mechanisms of retrospective clarity in her mind.

Jane served women of all ages. Often, the activists who answered calls from people seeking abortions, drove to secret locations where abortions took place and eventually learned to perform abortions themselves, were younger than their clients.

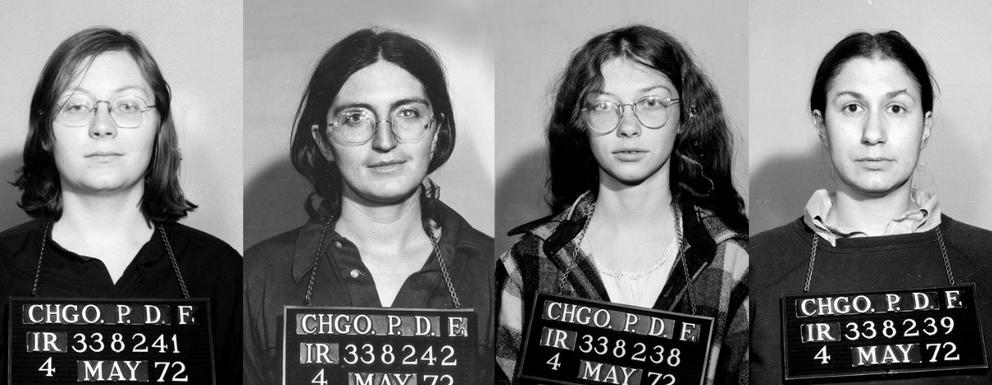

“On the verge of 80,” Arcana has been sharing stories from her time as a Jane for decades. She’s done so under her real name, in documentaries and news reports, in her own writing, in a chapbook that uses as cover art her mugshot from being arrested for abortion and conspiracy to commit abortion.

Some of the stories she recalls are heartbreaking. They reflect a time when access even to birth control was limited; when a patchwork of abortion regulations meant that women with the economic means to travel could find care in states that allowed abortion, but low-income people, or those with other responsibilities, like caregiving, could not.

The United States may be primed to return to that reality, except for the relatively recent development of self-managed abortion using the medications misoprostol and mifepristone, a much safer route than the surgical attempts women often made before Roe. In the early 1970s, abortion pills did not exist. Terminating a pregnancy meant navigating the underground, populated with unskilled practitioners. An unwanted pregnancy meant risking abuse, sexual violence and infection. It meant trusting strangers and scrounging for cash. The experience was humiliating and traumatizing, and potentially deadly.

Still, says Arcana: “I never had anyone say to me, ‘You know what? I’m changing my mind.’”

“Call this number and ask for Jane”

Arcana never intended to work for an underground abortion service. She was a teacher by trade and had no formal training in medicine. She grew up in the Midwest and, in her youth, had only a vague awareness of abortion.

In 1970 she was fired from her position as a high school teacher, along with two other educators, for nontraditional teaching methods. The experience radicalized her and lit up a controversy at her school and in her community. The ensuing monthslong public trial was a “huge education” for Arcana that made her see how politically motivated decisions could profoundly impact people’s lives.

It was in the midst of this political awakening that Arcana discovered she might be pregnant. Without any legal options for terminating a pregnancy, she sought the advice of a friend who was then a medical student. “I called him up,” she recalls. “‘Marty? Do you know?’”

He did. He responded within 24 hours, and gave her the instructions that would change her life. Arcana remembers exactly what he told her: “This line that has now become like a bumper sticker — or maybe a T-shirt — in my mind: ‘Everybody here says call this number and ask for Jane.’”

She called the number. Jane answered.

The voice on the other end of the line belonged to a woman whose real name was Ruth. From 1968 to 1973, the years the group was operational, more than 100 women played the role of Jane, including, eventually, Arcana herself. Arcana’s first volunteer role with the service was as “callback Jane,” returning calls like the one she’d made.

Ruth was a leader, the “the mom and pop of the service” along with another charismatic activist, Jody, as Arcana describes it; the group was founded by activist Heather Booth. Although Jane would come to be known as a collective in later years, Arcana says the group never described itself or functioned that way: There was a clear leadership structure, as she saw it, with Jody and Ruth at the top.

The power differential didn’t trouble Arcana, she said. But she does find contemporary descriptions of the group as a collective inaccurate. Arcana attributes these misrepresentations in part to a younger generation’s nostalgic desire to “want it to have been like that,” when in reality, activism and organizing are often fraught and complex. “It’s foreordained that it will be messy,” says Arcana.

In that initial phone call, Ruth spoke to Arcana for what seemed like a long time, for reasons that still aren’t clear to Arcana and never will be. Ruth and Jody have since died, although both women are memorialized in documentary footage from films about the group. (“It’s just such a kick in the head,” says Arcana. “I hate it when people die.”)

Whatever the reason, Ruth kept Arcana talking, and when Arcana found out she wasn’t pregnant and wouldn’t need the assistance of an underground abortion service after all, she called back to let Jane know. And “that was when she gave me the pitch,” Arcana recalls. For Ruth to invite a relative stranger into Jane’s activities “was very bold of her,” says Arcana. “She knew nothing about me, except that we just clicked in that very long conversation. And she was right. She was absolutely right.”

At the meeting Ruth invited her to, in a church just two blocks from her Chicago apartment, Arcana found she aligned with the women of Jane not just ideologically, but socially. “It wasn't just, ‘Oh, this is politically valuable and important for women's lives,’” she says. “I liked them. And I liked the way they talked about what they were doing, and why they were standing there in that little church.”

Although they would be facilitating abortions at great personal risk, Arcana recalls no major discussions about what it meant to commit a felony. “Everybody knew it was illegal,” she says.

“Why did I not mind that we were criminals?”

Abortion was illegal, and it still happened. Secretly, and, often, in unsafe situations. While some trained physicians provided abortions under the radar before Roe, procedures were often performed by people with dubious medical training and ties to organized crime.

Today, some abortions can be safely self-managed using the same pills prescribed by clinicians, a practice South American activists have used since the 1980s to ensure access to abortion in countries where the procedure is banned. The process is facilitated through a support model known as medication abortion accompaniment.

But in the United States before Roe, self-managed abortions looked very different. The preponderance of unsafe abortions meant major hospitals had wards dedicated to women who developed sepsis after attempted abortions, which can be fatal.

There is little concrete data on how many women died from unsafe abortions. According to pro-choice reproductive health policy organization the Guttmacher Institute, estimates range from 100,000 to 2.1 million deaths annually in the 1950s and ’60s. Greater precision is near-impossible. Deaths related to abortion were often underreported, especially those that did not involve law enforcement or medical documentation. In 2013, for instance, researchers at the University of Washington consulted the archives of both The Seattle Times and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in an effort to identify deaths linked to abortion that occurred in the Seattle area between 1945 and 1969. They found just 14.

The alternatives to self-managed abortion weren’t any safer. In Chicago, a heavily Catholic city with a strong mob presence, obtaining an illegal abortion often meant navigating underground economies controlled by the Chicago mafia.

That was Dorie Barron’s experience. She remembers her abortion with the Chicago crime syndicate as “a nightmare.” A group of strangers entered the room where she waited, took her money, induced a miscarriage, spoke to her cruelly and left her alone, bleeding, to miscarry into a toilet and complete her abortion alone, with no support. “It was brutal,” she says.

When Barron became pregnant again and needed a second abortion, she found a classified ad for Jane in a weekly newspaper, the Chicago Reader. Her abortion with Jane was opposite of the one she’d had with the mob.

“To have people come in, say ‘Where's your money? Do as you’re told,’ and then they did what they did and then they walked out and left us there, compared to these women being so concerned about our safety and our privacy, it was a difference of day and night,” she remembers. “Which is why, after I had the abortion, I called them and said ‘Can I volunteer with you?’ Because it was such an experience. It just opened up my eyes and my heart and I wanted to help these women. I was so impressed with their care.”

Unlike her previous experience, Barron was sent home from her Jane abortion with maternity pads, antibiotics to take in case of infection and clear instructions on what symptoms indicated an emergency that meant she should call her doctor, “and they called me at least twice in the following week to see if I was OK,” she says.

Jane was an inflection point in Barron’s life, as it had been in Arcana’s. The experience changed Barron’s view of women — whom, after a girlhood in a convent where she said she was mistreated, she hadn’t always trusted. Her second abortion led her to feminism, a career in public health and back to Jane. She joined a group of women providing free pregnancy testing and counseling out of a church in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood every Saturday. Before pregnancy tests were widely available, the group provided pregnancy screening and counseling based on the needs of the women they cared for, as well as advice to help them protect their privacy and obtain prenatal care or locate adoption services if they planned to continue their pregnancies. “We wanted to show them that Jane was there to protect women’s health,” she says.

The church didn’t know the group was associated with a clandestine abortion service. Neither did the medical supply house that provided the pregnancy screening equipment. This was a frequent tactic for Jane: capitalizing on those who underestimated women. Often, by not stating outright what they were doing, they were able to get away with it.

Arcana doesn’t recall ever worrying too much about getting caught. “It's only been since then, over a long time now — 50 years or so — that I've thought about: Why did I not mind that we were criminals? And many Janes have said this; like, ‘What were we thinking?’ And sometimes the answer to that question is not much — well, not much about that. We had other things to think about.”

Arcana’s husband at the time, who was a lawyer, “was concerned because maybe he’d lose his license because his wife was a felon.” But she has no recollection of ever worrying about what would happen if she was caught. In fact, as time passed, the Janes simply expanded their illegal activities, deciding to learn how to perform abortions themselves.

The decision stemmed from the discovery that the man who performed abortions for the group, whom Arcana identifies only by the pseudonym Mike, was not in fact a doctor. He was a seedy character with a background in construction, not health care. He was also a skilled abortion provider with a kind bedside manner. He could share what he knew with the Janes, Arcana recalls.

Some Janes felt this wasn’t a good idea and left because of it. But Arcana recalls Mike’s training fondly. She remembers seeing him demonstrate with tenderness how to hold a woman’s uterus with a hand on her belly during the procedure. “I was struck by the decency and the gentleness,” she says.

“What they’re doing is already illegal”

While it might be tempting to equate life after Roe with life before it, the legal landscape Arcana and her co-conspirators navigated during the years Jane was active was different from the one Americans now face. Abortion is still legal in 27 states. States like Washington have passed legislation protecting people from being criminalized for their pregnancy outcomes, and are refusing to cooperate with out-of-state lawsuits against providers. Washington, Oregon and California have joined forces in a multistate compact to shield patients from being prosecuted for seeking abortions throughout the West Coast. King County, the City of Seattle and the state of Oregon have all promised major gifts to the Northwest Abortion Access Fund, which provides financial and logistical assistance for patients seeking abortions in Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Alaska. In states where it is legal, medication abortion has been available through telehealth, with pills sent to patients by mail, since April 2021.

In states where it is not, pregnant people are able to access the pills through procurement websites, a partially underground economy quite different from Chicago’s crime syndicate. Having an illegal abortion used to mean forgoing clinician involvement. That isn’t true anymore. Services like Aid Access now send abortion pills to states where the practice is illegal, evading prosecution by operating overseas. Building on a longstanding tradition of abortion accompaniment, Mexican activists have established underground networks to bring abortion pills into the United States. Volunteer-operated funds connect patients traveling for care with lodging, transportation, groceries and clinic vouchers. All patients have to do is call. In states with abortion bans, much of this is against the law, and there’s no guarantee that entering a legal gray area won’t be met with prosecution. But illegal abortions are happening much more visibly than they once did, and self-managed abortion is much safer than it was in 1970.

Arcana sees some clear parallels between Jane’s careful phone work and that of contemporary abortion assistance funds. But the women who answered the phones and returned calls as Jane were doing something they knew was illegal, in a time before the anti-abortion movement. And while this situation put them at risk, it also gave them freedom. After abortion was legalized, and the anti-abortion movement grew into a political force, restrictions on abortion providers made working within a legal framework challenging by comparison.

The women of Jane may have faced other problems, but they didn’t have to contend with that. “For god’s sake, we were illegal, and we could be whatever we really wanted to be,” says Arcana. Despite being able to operate within the law, she said, contemporary abortion advocates “have restrictions and constraints on them that are applied sociopolitically, culturally. And it’s pretty rough for them.”

Listen to reporter Megan Burbank on the Crosscut Reports podcast where she discusses how the overturning of Roe v. Wade has shifted the landscape of abortion in Washington state:

Subscribe to Crosscut Reports on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon or wherever you get your podcasts.

The threat of anti-abortion violence also wasn’t yet in play in the late ’60s and early ’70s, says Arcana. “The anti-abortion movement had not yet changed the social and political circumstances such that we would either feel endangered or feel guilty or think that what we were saying might not be correct — none of that,” she says.

In some ways, Jane’s closest parallels are advocacy groups based in states that have already banned abortion entirely. According to the Guttmacher Institute, which tracks state-level abortion policy, 12 states are currently enforcing near-total abortion bans: Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas and West Virginia. Groups in states that have made abortion a crime operate with a disarming freedom that activists in states that allow abortion don’t have. Like the Janes, activists in states where abortion is banned know they are already breaking the law. That means they have more leeway in terms of what they can say to people who seek their services.

Riley Keane, former practical support lead for the Northwest Abortion Access Fund, puts it this way: “I was almost jealous of the fact that what they're already doing is illegal. So they don't have to worry about additionally giving medical advice. Whereas I can't tell people that [abortion drug mifepristone is] safer than Tylenol, or here's what to watch out for in terms of bleeding. I have to walk this really fine line of just saying medication abortion exists, and here are some websites that have more information about it.”

“Three years. That’s all we had.”

On May 3, 1972, Arcana was transporting a group of women to the apartment where their abortions would take place when she was intercepted and questioned by homicide detectives from the Chicago Police Department. The cops were following up on a tip from a woman whose sister-in-law had an appointment that day. She had contacted the police in an effort to stop it. Arcana and several other Janes were arrested, jailed and charged with homicide and conspiracy to commit abortion. Each faced up to 110 years in prison.

Arcana’s mugshot from that day has become almost iconic in the intervening years, used in media accounts of the abortion service and as one of her own book covers. In it, she stares ahead, her expression inscrutable, her posture upright. Even after the bust, Jane continued to provide abortions, and found a lawyer, Jo-Anne Wolfson, who filed repeated motions in an effort to delay the group’s trial, waiting out the clock as the U.S. Supreme Court heard Roe v. Wade. The strategy paid off: Abortion was legalized in January 1973, and the charges were dropped.

Roe was just the beginning of a new abortion fight, but it was the end of Jane. The activists moved on to other pursuits, having provided 11,000 abortions during their five years of operation. Arcana returned to education, then a long career as a writer and activist, and relocated to the Pacific Northwest, where she has lived for 28 years. Some women who were part of the service have never spoken publicly. Others have, but with precautions: In a 1995 documentary directed by Kate Kirtz and Nell Lundy, several Janes are interviewed using only their first names and wearing sunglasses to obscure their identities.

Still, their story has lived on in numerous retellings, including books; a second, more recent documentary for HBO (producer Daniel Arcana is Arcana’s son); and two feature films.

And the need for services like Jane’s has never stopped. In 1976, the Hyde Amendment banned federal funding for abortion, cutting off abortion access for low-income Americans. Hyde was one drop in the deluge of abortion restrictions that followed Roe, culminating in the gutting of the landmark decision itself last summer, when the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. The ruling entrenched long-standing inequity in abortion access nationwide, as states moved to limit abortion without any accountability to the legal check Roe had once imposed.

“Three years,” says Arcana. It’s something she finds herself saying a lot. “That’s all we had. Three years. And then the most vulnerable people couldn’t get abortion health care.”

Barron thinks the United States will someday embrace abortion rights again, but she doesn’t anticipate it happening within her lifetime. This is the challenge of any societal movement: living with the knowledge that you may fight all your life for a future you will never see, but continuing to fight anyway.

Arcana thinks of history as a long train. The world moves forward into the future, and we experience brief flashes of it based on the time and place we’re born into. And “wherever you get on that train, your station is part of what you think the train ride is all about,” she says. You can never see the whole thing, and you can get a clearer picture only by speaking with people of generations outside your own — the ones who were on the train before you got on, and the ones who will still be on it when you get off.