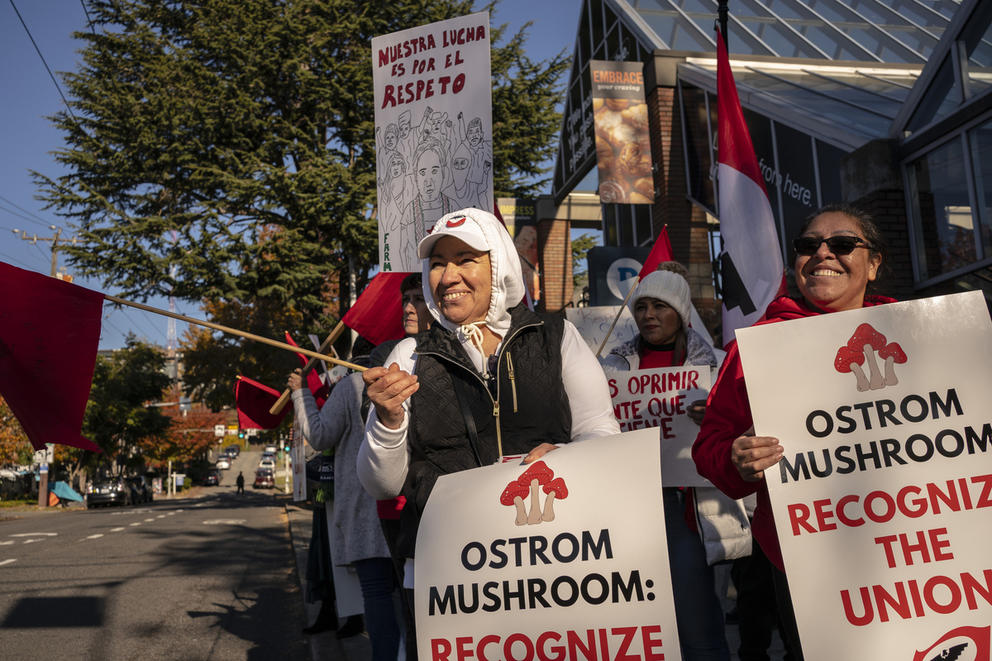

Workers, United Farm Workers labor organizers and supporters covered the entire storefront, holding various signs, including “We Feed You” and “Si Se Puede! [Yes, We Can!].”

For several months, Ostrom Mushroom Farms workers have been pursuing unionizing efforts to improve working conditions and address other issues with the company, such as its decision to fire local workers and replace them with H-2A guest workers.

The rally aimed to garner consumer support for those efforts, said Roman Pinal, a United Farm Workers organizer working with the Ostrom pickers.

When Ostrom opened a new facility in Sunnyside in 2019, there was community excitement about the economic impact a new company might bring to the Lower Yakima Valley.

Several years later, the company is receiving attention, but for an entirely different reason: The company has caught the ire of the Washington State Attorney General’s Office, which filed a lawsuit against the company in August. The office contends that Ostrom Mushroom Farms violated state laws by retaliating against workers who spoke out about working conditions, firing dozens of local workers and replacing them with international H-2A workers.

“There are power dynamics going on here,” said Attorney General Bob Ferguson in a news conference announcing the lawsuit against Ostrom in August. “It’s pretty clear who has power in this particular relationship.”

Ostrom workers want to get some of that power back through unionizing. Workers in mushroom farms elsewhere in the Western U.S. have been successful, gaining multiyear bargaining agreements, Pinal said. And that past success is what has kept the Sunnyside workers going through ongoing challenges, he said.

“They’re fighting for the same opportunity to have a say,” he said.

An Ostrom representative said Monday they planned to respond to Crosscut’s request for comment but have not yet.

Drawn to agricultural areas

Ostrom Mushroom Farms’ announcement in 2017 that it would relocate its plant from the Olympia area and build a $60 million facility in Sunnyside generated buzz among local community members and business leaders.

That enthusiasm translated into financial support. In 2018, the Yakima Herald-Republic reported that the Port of Sunnyside, which sold the property for the Ostrom facility, received $1 million in state funds to help offset the mushroom producer’s construction costs.

Many saw attracting the company as a significant economic development success. Officials also saw the facility as a complementary addition to a well-established agricultural industry in the area, which is home to several dairies; and Darigold, the Seattle-based dairy processor, has run a plant here for more than three decades.

However, Ostrom’s relocation to Sunnyside was a loss for Lacey, where Ostrom had run a plant since the late 1960s. Ostrom’s closing there led to the layoffs of more than 200 workers.

Company officials have said in news reports that the Yakima Valley’s established agricultural workforce was a draw.

Realizing worker value

Farmworkers are well aware of their value, said the UFW’s Pinal. That awareness has translated into speaking out about working conditions and organizing to have a say in the compensation they receive for their work, he said.

Historically, agriculture workers have been excluded from federal worker protections such as overtime and labor organizing. However, these workers have gained some protections through awareness campaigns, worker mobilization and legal action in recent years.

In 2016, two workers for DeRuyter Brothers Dairy in Outlook, an unincorporated area near Sunnyside, filed suit seeking payment for unpaid rest breaks, meal periods and overtime. The case went to the Washington Supreme Court, which ruled such actions violated the state constitution. The ruling eventually prompted the state Legislature to pass a law in 2021 that extended overtime to agricultural workers. Washington is just one of a handful of states with such a law.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020, workers staged protests and strikes at fruit-packing houses in the Yakima Valley over safety concerns and to push for hazard pay. Workers’ committees formed during those strikes were able to negotiate with employers. The strikes also generated public goodwill that made it easier to push for laws such as the one that extended overtime to agricultural employees.

And many Ostrom workers were introduced to the United Farm Workers through its campaigns for heat and smoke protection and immigration, Pinal said.

That introduction led to a widespread organization effort that included a petition signed by more than 200 people. In June, workers passed a resolution to be represented by United Farm Workers.

However, because farmworkers do not get National Labor Relations Act protections, such as pursuing a hearing from the National Labor Relations Board to unionize, farmworkers have to find other ways to gain recognition from an employer.

Farmworkers in several states have been successful after many years of organizing, including Washington grape workers gaining union recognition through United Farm Workers. Familias Unidas por la Justicia, made up of farm workers in the Burlington area, also gained recognition after several years.

Sharing worker stories

Now, Ostrom workers seek to bring attention to their organizing efforts and, in turn, press the company to address issues with workplace conditions. One way has been through the lawsuit filed by the state Attorney General’s office.

The office contends that Ostrom discriminated against its workers by firing 140 out of 180 of them — most of them female — and hiring male H-2A guest workers in their place over 17 months from January 2021 to May 2022. The company, the office claims, arbitrarily raised production standards without notifying employees. The lawsuit also contends that Ostrom has retaliated against workers who voiced concerns regarding working conditions by issuing unwarranted warnings and disciplinary actions.

Ferguson said during the conference that the case came to light after employees were willing to share their work experiences. Several current and former Ostrom workers spoke during the news conference.

“We can’t bring a case like this unless there are individuals willing to come forward, at some risk, and tell their story and press my team to tell that story to the court,” Ferguson said.

Ostrom has also been on the radar of another state agency. The state Department of Labor and Industries fined Ostrom $4,000 in early November for a work safety violation. The agency conducted an investigation in August and found the company failed to replace a drain cover leading to an employee falling into the exposed drain while cleaning. The company has appealed the fine, said spokeswoman Dina Lorraine.

A second inspection was done in October based on complaints from UFW, but the company found no violations and did not cite or fine the company, she said.

Now workers seek to further spread their message through events such as the Metropolitan Market demonstration, part of an extensive campaign to help gain widespread support. There are plans to have an event in Portland, where Ostrom’s mushrooms are also sold, according to Pinal.

The campaign will also share workers’ stories through social media. “We’re confident in our ability to tell [worker] stories and earn consumer support,” said Pinal.

Over time, Pinal said he hopes the workers' message will change from stories of difficult working conditions to more positive experiences.

“We hope to communicate the message to the Seattle consumer, the Portland customer, that Ostrom is respecting workers’ wishes to organize,” he said.