“A lot has happened and it’s all happening at once,” Maylor said, picking up her cat, Batman. She apologized for the hair dyes and makeup scattered across the bathroom floor, remnants of last night’s Halloween costume.

Taking her 10-year-old daughter trick-or-treating marks another small but meaningful win for Maylor, who regained custody after moving in last month. Stable housing also gave her time to interview for jobs, and this week she landed a position at a breakfast restaurant. For the first time in a while, she feels like things are falling into place.

“I’ve been struggling so long because of the abuse,” Maylor said. “If it wasn’t for … the emergency voucher, I wouldn’t be here right now, and my daughter wouldn’t be here right now.”

Maylor moved into that apartment using an emergency housing voucher (EHV), part of a new $5 billion program within the American Rescue Plan that represents a significant expansion of housing assistance into a system that serves just one in four eligible low-income households.

Nationally, about 50% of the emergency vouchers have been leased up since mid-2021. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), which oversees the program, boasts that EHV is seeing the fastest utilization rate for any housing voucher program in its history, though major cities with tight real estate markets like New York and Los Angeles have thus far struggled to place recipients in homes, with less than 25% of vouchers leased.

Housing authorities in Seattle and King County have used over 85% of their vouchers to lease apartments for more than 1,000 formerly homeless people. But in other parts of the state, hardly any of the vouchers have been used, putting those agencies at risk of losing funding if they don’t turn things around before a September 2023 deadline.

Asotin County’s housing officials say they returned their 15 vouchers (worth $186,000 in funding) to the federal government earlier this year. The housing authority in Skagit County has issued three of their 32 vouchers, with just one household successfully leasing an apartment, federal data shows. And in Clallam County, where a recent count located at least 178 people without a home, not one person has yet been referred into the program.

Housing officials who spoke with Crosscut said they lack the staffing to shepherd clients with high rental barriers through a tight market with few available units and even fewer willing landlords. Larger agencies in Tacoma and Renton report that sky-high rents have outpaced legal limits for what vouchers will pay. And in rural communities with patchy social service networks, housing authorities said partner organizations tasked with feeding clients into the program failed to deliver referrals or lost track of clients.

Sarah Saadian, senior vice president of public policy and field organizing at the National Low Income Housing Alliance, attributed some of the localized challenges to the unique approach of making public housing authorities work directly with homeless service providers, something they haven’t necessarily been asked to do before.

“There are legitimate reasons why it may feel like it’s taking a long time,” Saadian said, “but in fact I think we’re seeing really good progress here, especially when it comes to serving households that have the very greatest needs.”

Vouchers face a crowded market

It's not uncommon for voucher recipients to struggle in the rental market. A 2018 state law made it illegal for landlords to refuse to rent to someone because of their “source of income,” which is defined to include government housing assistance programs. But such discrimination remains widespread.

However, in multiple cases, housing authorities have yet to even issue vouchers to eligible clients – a necessary first step in the process to begin the housing search.

Sue Clark, executive director of the Asotin County Housing Authority in Eastern Washington, said that although there were clients who wanted the vouchers, they couldn’t find landlords willing to accept them, so the housing authority never issued any vouchers.

“People came in and inquired and we would have issued [them] if they could have found housing,” Clark said. “I can’t say there’s not a need for it, because there absolutely is, but there’s just not a lot of housing over here.”

Clark’s comments suggest the housing authority waited until clients found housing to issue the vouchers, which a HUD spokesperson said goes against program protocol. Clark also said that she understood the vouchers as temporary, with rental subsidy expiring after 18 months. That is not the case; the subsidy continues indefinitely. Clark did not reply to multiple follow-up calls seeking clarification on her comments.

This story is a part of Crosscut’s WA Recovery Watch, an investigative project tracking federal dollars in Washington state.

Asotin County’s failure to use the vouchers mirrors the challenges at other social service providers in rural Washington, where small teams in cash-strapped agencies are tasked with quickly distributing significant pots of pandemic aid. Yakima and Spokane counties were forced to return a combined $3 million in federal rent assistance this year after missing spending deadlines.

Skagit Housing Authority has issued just three of their 32 vouchers thus far, according to HUD’s data dashboard. Citing a 1.5% vacancy rate in the county, executive director Melanie Corey said the agency is making a strategic choice to issue the vouchers in small batches to avoid having voucher-holders compete against each other for rare openings.

“If you have 32 vouchers out there and they’re all applying for one unit that’s open, you’re not going to have success,” said Corey, who added that two more vouchers have been moved to other jurisdictions at the request of clients.

One might assume that finding people eligible for this program – that is, anyone currently or previously experiencing homelessness, or at risk for it – should be the easy part. Yet Corey noted an additional 14 households are in the pipeline, some have completed all the paperwork and are ready to go – but the agency cannot find them.

“Some of them have phones, some of them do not. Sometimes their phones are turned off,” Corey said. “Physically finding them is a problem.”

The Community Action Council of Skagit County is tasked with doing outreach to encampments and referring clients into the program. Dulce Vazquez-Cruz, the council’s resource center manager, said losing track of clients is fairly common.

“The client could be located in Mount Vernon and then you find out that they are somewhere in Sedro-Woolley or moved over to Whatcom County to seek services there,” she said.

EHV program offers new resources

Getting an apartment with a housing voucher in the United States is a bit like winning the lottery.

Just a quarter of those who qualify for housing choice vouchers, also known as Section 8, actually get one, typically after sitting on a waitlist for years (King County’s waitlist currently numbers 19,000 households). People living out of cars or on the streets often struggle with the paperwork and bureaucratic burdens required to apply and maintain a spot on waitlists that can stretch on for years. Those lucky few enter a competitive rental market with landlords hesitant to accept them and prices sometimes higher than the voucher will cover.

The new program tries to work around those historic problems. Recipients get pulled not from housing authority waitlists but from a local organization that serves as the first point of contact for homeless people seeking services. Clients have 120 days to use the voucher, double the amount of time Section 8 holders get, and that window can be extended.

The EHV program also provides discretion to housing authorities to hire navigators to assist in the housing search, pay move-in fees and security deposits, and offer landlords incentives to accept voucher-holders. Aley Thompson, rental assistance director at Tacoma Housing Authority, said it’s the first time housing authorities have had those resources at this scale.

“HUD has never funded services like this before,” Thompson said. “I would love it if all of our programs could do this moving forward, so we could be more successful.”

While Thompson believes these changes have helped, Tacoma is one of the larger authorities in the state that is leasing below the national average, and will need to ramp up to avoid losing vouchers by next fall’s deadline.

Many area listings remain above the federal “fair market rent” limits HUD allows the vouchers to cover. HUD recently announced a national increase to those market limits, which could help open new housing to voucher holders. But unless Congress provides a corresponding increase in funding to the program in its federal budget, Thompson said local housing authorities may end up with fewer vouchers they can offer to those in need.

“It could mean I’m not leasing to new families anymore,” Thompson said. “Housing authorities have a lot to consider when they increase the value of a voucher … that money has to come from somewhere.”

King County makes headway

Saadian, of the National Low-Income Housing Alliance, pushed back on the idea that market conditions had reached the point of undermining vouchers’ effectiveness. An analysis by the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities found that over the 2010 decade, public housing authorities on average used nearly 100% of Section 8 voucher funding.

“It’s a challenge, but I don’t want to overstate how big the challenge is,” Saadian said. “Because at the end of the day, the funds that Congress provides for vouchers are spent and get spent on time.”

The biggest problem with the program, Saadian added, was too few eligible people actually getting assistance. As far as EHV, she added that other jurisdictions should study King County’s successful approach.

“There are places in high-cost markets,” she said, “that are doing a really good job of using these vouchers.”

Find tools and resources in Crosscut’s Follow the Funds guide to track down federal recovery spending in your community.

After a slow start that was attributed to the rollout of the Regional Homelessness Authority, King County – which has a vacancy rate of 4.3% – is now over 90% leased up, drastically better than places like New York and Los Angeles.

Peter Lynn, Chief Program Officer at the King County Regional Homelessness Authority, credited a complex system in which 80 different organizations signed up to provide referrals, ranging from the YWCA to health care facilities and tribal entities. Each organization agreed to support the clients from the application process through the housing search and one year of tenancy, Lynn said, despite not being paid for that work.

“It was amazing the response that we got,” Lynn said, adding that having a committed advocate shepherd clients through the process was vital to their success.

Policy changes at the state and national level could also help more voucher holders obtain apartments, Saadian said – things like enacting legal protections against source-of-income discrimination and stronger enforcement of fair-housing laws.

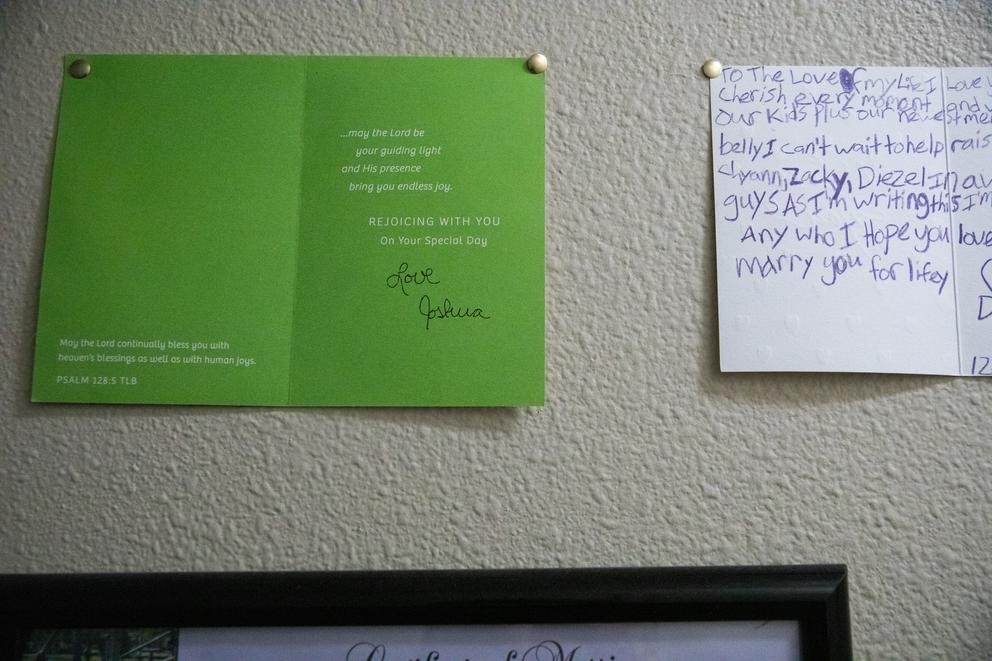

Maylor, sitting in her new apartment, reflected on the “rocky road” that led her here. It may not be possible to know how things might have turned out differently if she’d had access to housing aid before things took such a dark turn. But Maylor is confident that without the help she has now, things would be a lot worse.

“If it wasn’t for getting that voucher,” she said, “I wouldn’t have gotten away from everything.”