But while attacks on bigger, more prominent companies are making headlines, it’s also an increasing problem for Washington state’s small and local government entities, including municipal and county governments, health care organizations and school districts. Many of these entities have an IT staff in the single digits — nothing to compare with a major city like Seattle, which has a dedicated IT team of over 600 employees, 18 of whom are specifically dedicated to cybersecurity.

Para leer este artículo en español, haga clic aquí.

A nationwide spike in cyberattacks prompted the Biden administration to include $1 billion in cybersecurity grants for states in its infrastructure bill passed in November. Although there are significant set-asides for small and rural governments in the program, questions remain about how readily small public entities will get access to the funds and what precisely the grants will pay for.

Jessica Beyer, a lecturer at University of Washington and the co-lead of the Jackson School of International Studies’ Cybersecurity Initiative, said small city and county governments are prime targets because they have limited IT resources and rich amounts of data. That often makes them reluctant to talk on record about their experiences.

“If you say, for instance, ‘We’re underfunded and need more for cybersecurity,’ ” Beyer said, “talking about things like that can indicate you might be vulnerable, and ripe for an attack.”

The Northshore School District — which serves Bothell, Woodinville and the suburbs north of Lake Washington — learned this the hard way.

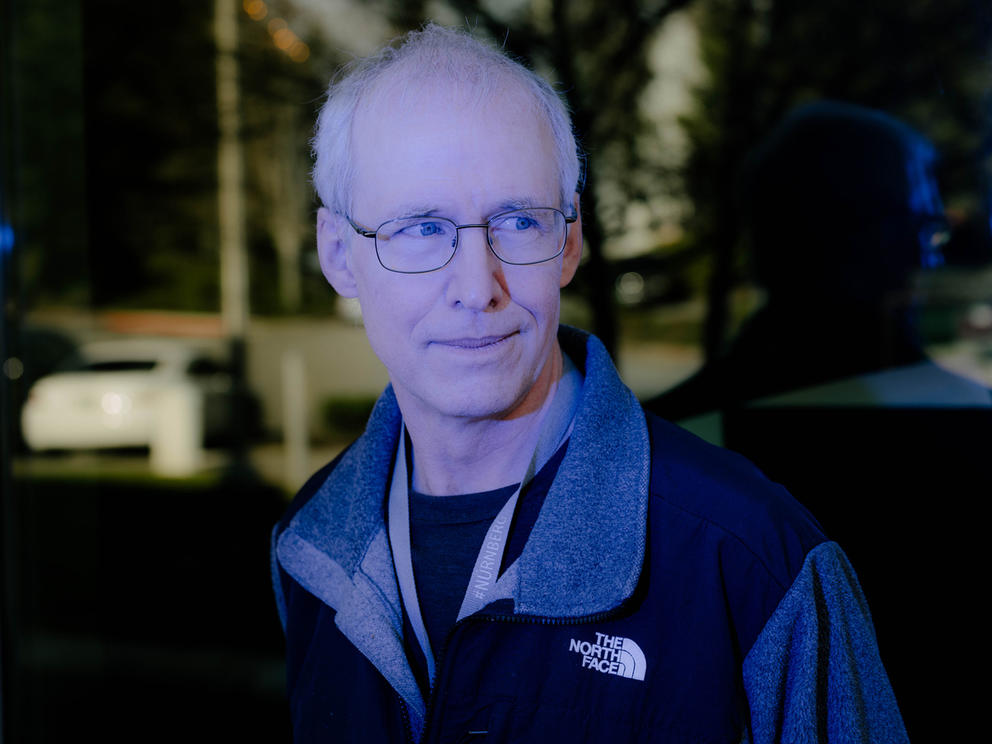

In the early hours of a Saturday morning in September 2019, a computer systems employee at Northshore noticed one of the district's servers was acting strangely. Northshore system administrator Ski Kacoroski took the employee’s phone call at around 5:30 a.m. and admits now he didn’t think the problem was especially urgent.

But later that morning, Kacoroski noticed other servers were acting weirdly. And then, suddenly, all staff and students were locked out of the system. Kacoroski realized the district was in serious trouble.

Later, a cryptic message made it clear to Northshore’s IT staff what was going on.

“We saw an HTML file parked somewhere,” Kacoroski said. “It said: we're going to be encrypting your files.”

Though the district’s email system and website were still up and running, nearly every other system was inaccessible, including payroll, student records and even the lunchroom cash registers.

“When you first look at something like this,” Kacoroski admitted, “you don't realize it's a ransomware attack.”

It’s a remarkably candid admission, and now that Northshore has repaired its systems and beefed up security, district officials are talking publicly about their experience.

“We've talked to a lot of our colleagues, especially in K-12,” said Allen Miedema, Northshore’s executive director of technology. “We're focusing on public entities, which are notoriously understaffed and under-resourced for this kind of work.”

In a ransomware attack, which can start with a phony “phishing” email that looks as if it’s come from a trusted sender, hackers disable access to computer systems, hold them hostage and then demand payment in cryptocurrency in return for the electronic keys to the system. For local entities such as schools and health care providers, the results can be destructive. In addition to denying access, hackers can (and have) publicly exposed students’ and patients’ private information.

Luckily for Northshore, Kacoroski’s team was able to restore access without the district’s insurance company having to pay the ransom.

A close call

In May of 2021, Luke Davies, health administrator of the Chelan-Douglas Health District, got a call from the FBI letting him know that the agency was monitoring hackers that might conduct a cyberattack on his organization soon.

“We thwarted this attack, but if we hadn’t been contacted by the FBI, I don’t think we could have done it in time,” Davies said.

Davies, whose organization provides affordable health care and preventive services to 126,000 patients in Central Washington, doesn’t know how the FBI knew hackers were attempting to get into the organization’s system. But he noted that there had been several high-profile attacks earlier that year in other parts of Central and Eastern Washington, including a ransomware incident that shut down most of Okanogan County’s computer services that January. (Okanogan County officials did not respond to requests for an interview for this story.)

Chelan-Douglas Health’s IT team quickly identified vulnerabilities and worked with its internet service provider to patch up the system’s defenses.

Since then, Davies' team has worked to better educate its staff to be vigilant about what links they click on, monitor old accounts to ensure no one’s trying to activate them and upgrade hardware and software. But that’s a big ask for two rural counties with small budgets.

“Public health in Washington has been underfunded since 2007,” Davies said. “And the level of infrastructure here was very antiquated. When I came on, in 2020, we were surplusing TVs from circa 1998.”

In February, Chelan-Douglas Health received $939,000 in American Rescue Plan Act funds, at least $500,000 of which will be used to shore up and modernize the organization’s computer systems and hardware, Davies said.

Davies feels it’s important to share his organization’s experience so that other rural communities become aware of what could happen to them.

“In talking with my colleagues, it’s clear that no one likes to talk about this,” he said. “From a public health perspective it reminds me of how people really don’t like to talk about sexually transmitted infections. This is the cyber equivalent of that.”

Silence in response

Many rural government entities and school districts that have experienced recent ransomware attacks declined to be interviewed for this article or simply ignored requests.

In Grays Harbor County, Harbor Regional Health was hit with a $1 million ransomware attack in 2019 that risked exposing information of 85,000 patients. According to the industry blog Health Security, Harbor Regional Health agreed to a $185,000 settlement with patients affected by the computer downtime, which reportedly lasted two months.

Harbor Regional Health declined to be interviewed for this article.

Similarly, the Port of Kennewick suffered a ransomware attack in November 2020 in which staff were locked out of computer systems. Hackers demanded a $200,000 payment, the Tri-City Herald reported.

The port declined to be interviewed for this article, though spokesperson Tana Bader-Inglima wrote in an email that the port quickly notified law enforcement, reset passwords and assessed security vulnerabilities. It also reported the incident to state regulators, as has been required by state law since 2015.

Port officials refused to pay the ransom, the Herald reported. Public records obtained by Crosscut did not show evidence of the port making any recent large payments in bitcoin or other cryptocurrency. However, it’s unlikely the port would have paid ransoms directly. In most cases, insurers pay out ransoms, and those insurers are reluctant to go on record publicly about the number, or dollar amount, of ransoms they’ve paid.

The Washington Schools Risk Management Pool is one of two statewide organizations that help public school districts collectively obtain insurance and reduce risks. According to the organization’s executive director, Deborah Callahan, school insurance claims for ransoms in Washington state are “very rare,” though she acknowledges that “it is clear that the risks and magnitude of ransomware attacks and other cybersecurity breaches are on the rise for everyone.”

Callahan wrote in an email that two members of the risk management pool organization had ransom claims in the past two years, “with minimal to no payouts.”

According to Miedema, director of technology at Northshore, the school district spoke with its insurer shortly after it was clear the district was dealing with a ransomware attack. He noted that in the first few days after the attack, the district’s insurance company took control of the incident investigation, and asked if Northshore was considering paying a ransom.

“It’s not as easy a question as it seems,” Miedema said.

Accurate data on how many ransoms are paid and the rate at which hackers actually release encrypted data after victims make payments are hard to pin down. One industry report estimated that 30% of organizations experiencing ransomware attacks pay ransoms.

Though the FBI’s formal policy discourages ransom payments, many organizations find they have no other choice. Miedema said the FBI agents he worked with told him that nearly all hackers demanding ransoms deliver on the encryption keys quickly.

“They’re business people,” Miedema said. “If you pay a ransom and they still don’t give you your stuff back, you're going to spread the word — and they’ll go out of business.”

Though Northshore officials determined they didn’t need to pay their attackers, many other organizations apparently did around the same time.

“Within the first week after our attack, the insurance company told us they negotiated five or six ransom payments over that weekend,” Miedema said.

More funds, lessons learned

In November, President Joe Biden signed the $1 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which included a $1 billion grant program managed by the Federal Emergency Management Agency to help states prevent cyberattacks.

An email from a FEMA spokesperson said the agency will administer these grants and that states and tribal governments will be required to submit a plan outlining how the money will be used to improve cybersecurity. FEMA said it’s up to states to decide how to allocate the funds, but 80% must go to “local units of government” and at least 25% must be set aside for rural communities.

What defines a local government or rural community has not been outlined yet. In addition, the federal Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency will assist FEMA in creating program goals and reviewing each state’s cybersecurity plan. FEMA’s spokesperson said the grants can help to reduce cybersecurity vulnerabilities and increase capabilities, but noted that organizations cannot use the funds to pay ransoms.

“I’m excited about this [program],” said Beyer of UW’s Cybersecurity Initiative. “We know how vulnerable cities and schools are. Lack of resources is something everyone points to.”

Mike Sprinkle, director of IT with Clark County, has been closely examining the federal grant program and waiting to see how the money will be allocated.

Clark County previously applied for and received over $7 million in federal American Rescue Plan funds to completely overhaul its computer architecture and increase cybersecurity. Sprinkle said the program helped his IT department segment its network to decrease the risk of entire systems being hacked, and to hire a service that provides security monitoring 24/7.

“My big goal has been to make sure that Clark County IT and myself are not in the newspaper,” Sprinkle said with a chuckle, noting that so far the county has prevented an attack.

He noted that while Clark County has an IT staff of about 50, many smaller counties have much smaller IT staffs and could really put the FEMA funds to good use.

Annie Searle, an associate teaching professor at UW’s Information School who focuses on cybersecurity, said small municipalities can take simple steps that do a lot to prevent attacks.

Searle said simply updating software patches and installing all operating system upgrades can make a big difference.

“If those two things were done, perhaps 80% of the problems would go away,” she said.

The Washington State Auditor’s Office has also performed more than 60 free security audits to local governments, school districts, health care systems and tribes since December 2021.

“In those 60 audits, we’ve identified more than 500 critical vulnerabilities,” said Erin Laska, IT security audit manager with the State Auditor’s Office. “And these are really the worst type of weaknesses that can be used to cause a breach.”

Kacoroski, Northshore’s system administrator, said one thing he would advise other organizations to do is create an “air gap” between a system and various external backups of data, such as a tape or USB drive that completely pulls data from the server.

In addition, taking an inventory of the real-world systems, such as cash registers, vehicles or heating controls that could be affected by an attack, can also be helpful, Miedema noted.

“You have all these little systems that you install and it just works and you forget about it — and then everything comes crashing down,” he said.

After its attack, Northshore managed to pay its employees after some tweaking of its systems, but it soon became apparent that many school systems couldn’t function with the computers down. Students couldn’t purchase lunches because cash registers didn’t work. New students couldn’t get assigned bus routes. Heating systems couldn’t be turned up when a cold spell hit.

Even the district’s football scoreboard was affected.

“We have a beautiful football stadium, and it has this great reader board on it. And you’d think that's not critical,” Kacoroski said. “But the Friday after the attack, ESPN was signed up to put one of our football games on TV. So we had to have that reader board up and running.”

Eventually, his team got the scoreboard working.

Both Kacoroski and Miedema urge small organizations to take the threats seriously and to talk to one another about what they’ve learned.

“We shouldn't be ashamed of the fact this happened,” Miedema said. “The fact is, school districts and public entities are outgunned in this fight. They really want to hit you, and it’s going to be pretty hard to stop — which is kind of sobering.”

The UW’s Beyer agrees.

“The idea that you’re eventually going to suffer some sort of cyberattack is a better way of thinking about things,” she said. “Thinking about resilience and recovery rather than the idea you can prevent everything. Yes, try not to click on those links. But have a plan for when it does happen.”

Correction: A previous version of this story included incorrect job titles for Beyer and Searle.