Small is Northern Cheyenne and a researcher who has both dug through old federal records and examined burial sites with ground-penetrating radar to find unidentified remains of Indigenous people in the Pacific Northwest. That included examination of the Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon. an off-reservation boarding school run by the Interior Department’s Bureau of Indian Education.

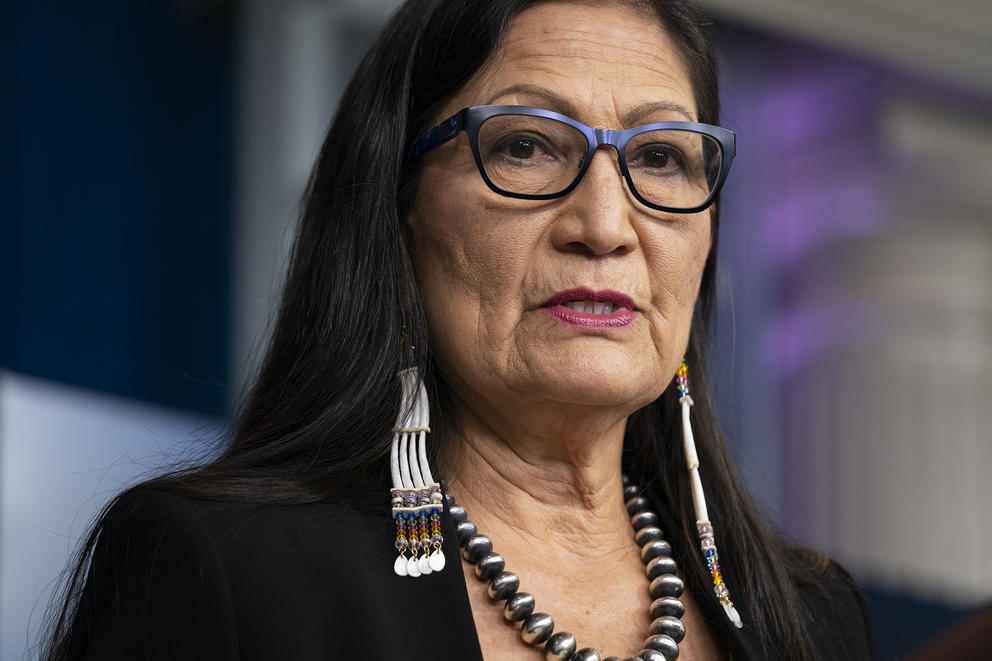

The kind of work Small is doing is poised to expand dramatically under the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative that Haaland announced. It aims to find old school locations and burial sites on them, where researchers would search for unidentified remains, with the goal of identifying who died and what tribal affiliations they had. In her announcement, Haaland acknowledged the generations of trauma inflicted upon Indigenous people through brutal practices at federally run boarding schools.

“The Interior Department will address the intergenerational impact of Indian boarding schools to shed light on the unspoken traumas of the past, no matter how hard it will be,” Haaland said in a statement announcing the initiative. “I know that this process will be long and difficult. I know that this process will be painful. It won’t undo the heartbreak and loss we feel. But only by acknowledging the past can we work toward a future that we’re all proud to embrace.”

The work of finding the remains is itself painful, as Small can attest. She said the emotional impact of being at the burial sites and discovering unidentified bones — often of young children — can be overwhelming.

“I will lose the train of thought immediately,” Small said, as she recalled standing in the Chemawa cemetery searching for remains. “It is daunting and it’s so soul-impacting. And if you’re not impacted by it, then maybe you’re in the wrong area.”

Small discovered 222 sets of remains at Chemawa. That’s more than the 208 she said the federal government had documented at the school cemetery.

But that’s only one problem. Small said other than one row of graves, the grave markers and the locations of remains don’t match up. She noted her radar technology could penetrate only one meter into the ground, leaving her to suspect there are more remains buried farther down, which she’s hoping to find when she returns to the Salem campus in September.

This story was originally published at Oregon Public Broadcasting on June 24, 2021.

Chemawa may prove to be one of the easier places to start because it’s a long-known school site that’s been used almost continuously since the 19th century. But the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition has created a list of at least 367 school sites across the country — the vast majority of which haven’t operated as schools for years. It lists nine schools in Oregon: the current Chemawa site in Salem and its predecessor in Forest Grove, as well as seven other locations scattered throughout the state.

As Interior Department officials plan their investigations of school burial sites, Small emphasized two attributes for people leading the work: that they be adequately trained on how to use the ground-penetrating radar technology, and that they’re Indigenous.

“It could turn into just another Western colonial agenda,” Small warned. “They need tribal representation on each project — somebody that knows what they’re doing.”

Haaland’s initiative doesn’t intend to stop with locating sites and finding remains. The effort, led by Bryan Newland, principal deputy assistant secretary for Indian affairs, includes identifying who these people — largely children — were.

The initiative won’t just be emotionally and technologically challenging. SuAnn Reddick, former historian at Chemawa, anticipates problems originating from poor recordkeeping and issues from disturbances to the land. Reddick warned of disturbed grave sites and mountains of federal “sanitary records” — as some federal agencies called birth and death documents decades ago.

“Unfortunately many or most of the school cemeteries (including Chemawa) were demolished at some point, and many of the school enrollment and sanitary records are buried deep in the government’s archival bowels,” Reddick told OPB. “Finding names and tribes of the children will be a huge challenge.”

There can be cultural conflicts over the investigative research, as well, Small said. While some information can be gathered matching radar data with records and archival research, nailing down precisely how old a person was, whether they’d been malnourished, or what tribe they belonged to likely requires DNA analysis. And that kind of forensic technology is controversial among tribes, according to Small.

While the effort is daunting, Small said she found Haaland’s announcement “fortifying.” It’s ultimately aimed as much toward the present and future, as it is in examining the past, according to Haaland, the first Indigenous person to serve as a cabinet secretary.

“It is a history that we must learn from if our country is to heal from this tragic era,” Haaland said in an op-ed recently published in the Washington Post.

Small, for her part, is measuring her expectations for the upcoming initiative. The Interior Department follows efforts in Canada to find unidentified remains of Native children in that country, as well as an attempt at “truth and reconciliation” in its relationships with Indigenous nations. Small said she sees “truth” and accountability and other positive strides in Canada, but not true “reconciliation.” In the U.S., she sees a chance for some measure of progress in the next few years.

“There’s a window that we’ve got time to put in these programs and to create, facilitate ... healing. And if we do that, then that would be great,” Small said.