Washington state is a hub for international students, ranking 11th in 2020 among the states in the number of international students, according to the Institute of International Education. Even during the pandemic, the institute found, over 26,000 international students were attending Washington universities. More than a third came from China, and large numbers were from Vietnam, India and South Korea.

Like Chen, many international students had to adjust to extraordinary time differences to attend their online classes while code switching between English and their mother tongue. It was largely on their shoulders to push through the unprecedented challenges brought by the pandemic.

Because of the time difference, American online classes ended up taking place in the predawn hours in Asia. International students had no choice but to set a sleep schedule from morning to afternoon, and socialize, exercise and study as the sky gradually darkened.

Had he been in Seattle, Chen’s spring schedule would’ve been reasonably relaxed, with classes from 10:30 a.m. to 5:20 p.m. Monday and Wednesday. In Taiwan, though, that meant Chen was in class from 1:30 a.m. to 8:20 a.m. Tuesday and Thursday. To stay awake in class, Chen usually took a nap after dinner, then woke up at midnight to a dark house and sleeping family.

“I liked to take a shower to freshen myself before class, and I tried to be as quiet as possible to avoid waking my family,” Chen said. “It was funny because preparing to go to school was like [being] a sneaky thief.”

Luckily, he said, he had a break at 3:20 a.m. that was long enough to make a cup of coffee.

“It really made my heart ache to see my son, who stayed up all night, was still in class when I went out to work in the morning,” Chen’s mother, Belinda Ye, recalled.

Despite the difficulties, international students still found positives during a difficult year. Chen recalled his life in Seattle, where basic living expenses amounted to $2,000 a month. He has saved money living at home, and, because the pandemic was under control in Taiwan well before the United States began reopening, he had chances to recreate with friends.

Of course, not all international students were studying in countries that had the coronavirus well in hand.

Victor Simoes, a Brazilian student majoring in journalism and public interest communication at University of Washington, will be entering his junior year when he returns to Seattle in September. While widespread vaccinations in the U.S. have helped deal with the virus, COVID-19 has yet to be constrained in Brazil. And, as many of his classmates in Seattle were celebrating the presidential succession, Simoes was protesting Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, a conservative nationalist sometimes referred to as the “Trump of the Tropics.”

“He doesn't believe in the pandemic and the power of the virus. That takes much of my time, mentally, because it stresses me a lot,” Simoes said.

“I don't think that universities take that into account,” he added.

Studying from his home in Florianopolis, an island city in southern Brazil, Simoes found online college dull. He missed his classmates and felt alone.

“When I was in in-person classes, [students] were all in the same city and environment. We ... had something in common. And now, I feel like I'm in a different world,” he said. “I don't feel as a part of the group, and it doesn't motivate [me] to go to class or engage.”

Simoes said he had a hard time being in online learning. Some professors didn’t consider students’ circumstances, he said, and taught as though “everyone is in the same situation.” But he knows first hand that international students face very different social realities than their American peers.

University of Washington student Victor Simoes spent the 2020-2021 school year studying online from Brazil, where anti-government protests have become common. He calls this one of the situations universities do not take into consideration with international students during the pandemic. (Victor Simoes)

Across Washington, universities' student services offices scrambled to keep international students in school. At Washington State University in Pullman, the international student services office worked to assist students and improve virtual learning after the campus closed last year. Technology support was expanded and emergency funds were used to help international students. The university’s Campus Friends program, which helps connect American and international students with one another, launched The Gather Town so international students could meet, chat and play games with their peers around a virtual campus.

“For all students, there was certainly the adaptation and challenge to online learning,” said Kate Hellmann, director of international student and scholar services at WSU. “That's especially challenging for international students.”

Despite the challenges posed by the past year, Simoes said he looks forward to being back in Seattle, and knowing that he is staying there will help ease the personal worries brought by COVID.

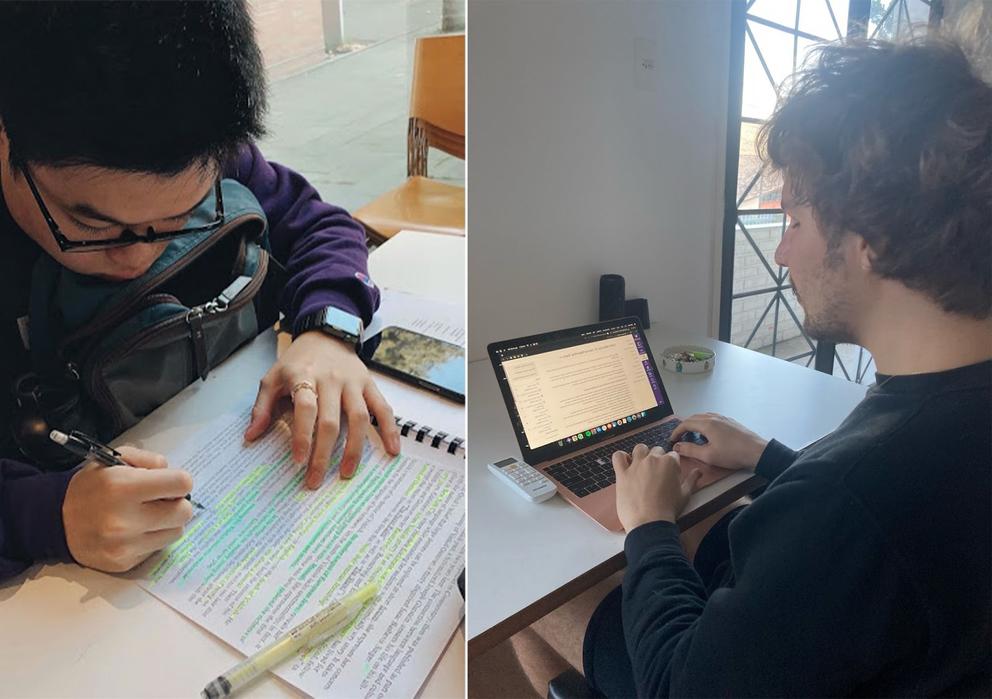

Through all of the challenges international students have faced, many look forward to getting back to campus after the pandemic — reconnecting with friends and peers, cramming for finals in the library and getting back to the college experience they signed up for. They want to finish the college journey in Washington.

“When I get there, I think I’ll have a sense of what I need to plan for the future,” Simoes said. “Having that sensation is something I'm craving.”