Two years later, he can speak English as well as he speaks his native Farsi. He argues that he is basically already 11 years old since his birthday is coming soon. He knows he wants to be a lawyer when he grows up. And he hopes to make the school soccer team this season and loves to talk about the different places his friends and classmates come from.

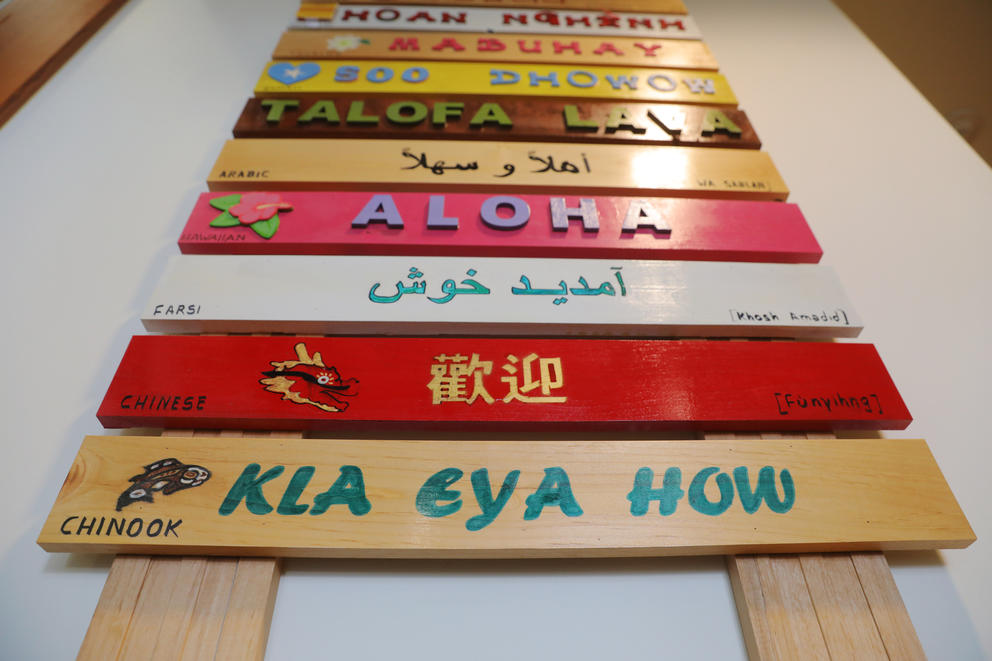

A majority of his fellow Parkside students are immigrants and refugees or have asylum status. They come from a variety of countries: Afghanistan, Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Russia and Ukraine. Several languages, like Swahili, Farsi, Pashto, Dari, Spanish, English, Arabic and more, appear on colorful signs and posters and are heard in school hallways.

Global events, including the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan in 2021 and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, have brought refugees to Washington communities like Des Moines. And nearly half of all refugees who come to the state are under 18, according to Sarah Peterson, office chief and state refugee coordinator for the Office of Refugee and Immigrant Assistance in the Department of Social Health Services. And those numbers have more than doubled in each of the past two years.

“I think kids are often the reason why people come to the United States,” said Peterson. “On more than one occasion, I’ve had a parent say, ‘I came so that my child can have a better life.’”

Baheer’s father, Ahmad Hedayee, 38, said his family’s life in the U.S. is amazing in comparison to what they would have had to endure if they had stayed in Afghanistan.

“I have work, my kids come to school, my wife is going to college, everything is good and we’re really happy with this life,” Hedayee said.

First steps

More than 14,000 refugees and other humanitarian immigrants have come to the state in the past two years, according to Peterson. The largest subgroups are from Afghanistan and Ukraine, followed by Syria, Cuba and Venezuela. Most are coming to King, Spokane, Snohomish and Pierce counties so the immigrants and refugees can join existing communities of newcomers and receive culturally responsive resources and linguistic help.

Over the past two fiscal years, the Office of Refugee and Immigrant Assistance has invested nearly $70 million to support more than 16 programs and services for eligible refugees and immigrants. Peterson said 91% of this money comes from the federal government and the rest from the state budget.

Washington enrolled more than 4,000 Afghan children and 6,000 from Ukraine in the 2022-2023 school year alone. The large number of incoming students is difficult for both the state and the districts to track, so some schools may be missing out on the state funds available to support their immigrant and refugee students, according to Peterson. These programs are opt-in and schools need to apply for the money, but Peterson said some schools aren’t aware of this resource.

The state also has difficulty tracking the impact this money has on communities since they can’t directly check with individual students and their families. They must rely on their community partners for updates. And a lot of this work is done quickly in response to emergencies, as they had to do when war broke out in Ukraine, so that adds another level of difficulty.

First steps for these families – and the agencies helping them – are housing and then school.

Schools and community organizations work together to support them, generally placing the newcomers with other people from the same country, religion and culture to ease their transition.

“Parkside is my second home,” said Ahmad, who was hired as a bilingual interpreter by the Highline School District and then later as a paraeducator at Parkside to help teach English to immigrant students. “This very classroom we are in is where I started working,” he said of the classroom where incoming immigrant students learn English.

The journey

In Kabul, Ahmad worked as a general services assistant at the U.S. Embassy, where he was invited to apply for Special Immigrant Visas for himself and his immediate family. They left around the same time the U.S. troop withdrawal began. Most of their extended family remains in Afghanistan, but Ahmad says they keep in touch through video and phone calls.

Although Baheer was only 7 at the time, he vividly remembers each stop along the way.

He remembers his father waking all of them up at 2 or 3 a.m. and saying it was time to go. They drove their car to Kabul International Airport and carried their luggage filled with clothes, mementos and essentials. They waited outside in the summer heat until the late evening with “100,000 or 200,000 people” who were all trying to escape.

Then they repeated this routine for the next two to three days, waiting to board a plane. The day before they were able to leave, Baheer remembers, he heard loud bangs and yelling from those he called “armies” – U.S. soldiers – to leave their bags and run inside the airport buildings for safety.

Ahmad said those loud bangs were from a suicide attack at the back of the airport. His family was finally able to board a plane to Germany after days of uncertainty and anxiety. In Germany they spent almost two months sharing a large tent in a refugee camp with about 300 people, with no restrooms and having to ration food to the point of being allotted only one banana for two children or a large hard black loaf of bread for the whole family.

Baheer said he wore the same outfit, including underwear, for 15-20 days without showering. They were given donated clothes and a blanket to keep warm at night, but look back at their time in Germany with grimaces, and have agreed never to return.

When the Hedayees finally arrived in the U.S. in 2022, the whole family said they immediately felt welcomed by American soldiers at Fort Gregg-Adams in Virginia. The soldiers carried their bags to their hotel room and even bought them Afghan food, which Ahmad said they hadn’t eaten since beginning their journey.

Baheer remembered feeling so happy to finally take a shower after wearing the same dirty clothes for so long. The family then was transferred to Pennsylvania, where Ahmad said they were taken to a room with a large table full of snacks like chips and candy. The children asked if they could have some, but, after having to ration their food in Germany, they took only one bag of chips and a piece of candy. They were elated to learn they could eat as much as they wanted.

Ahmad requested a move to Washington since his brother lived here, and the International Rescue Committee set them up in an apartment complex close to Parkside Elementary, where Baheer and his sister Sama, 9, enrolled in January 2022.

Jennifer McLaughlin, senior program manager for youth and education at the IRC, said the process of resettling families into housing and enrolling the children in school can take months, often with several relocations along the way. The IRC has a partnership with Highline School District; McLaughlin said they began their work with one middle school in King County in 2023, and now it’s the county with the most people they serve.

Once a family is settled, they go through school orientation with a support team of social workers and staff members. This is also when families learn about the U.S. education system and a variety of other support services from language assistance to the school lunch program.

Challenges of refugee influx

More than 250 different languages are spoken in Washington, according to the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction. Many immigrant children are eligible for the state’s Transitional Bilingual Instruction Program when they start school here, especially if English is not their primary language.

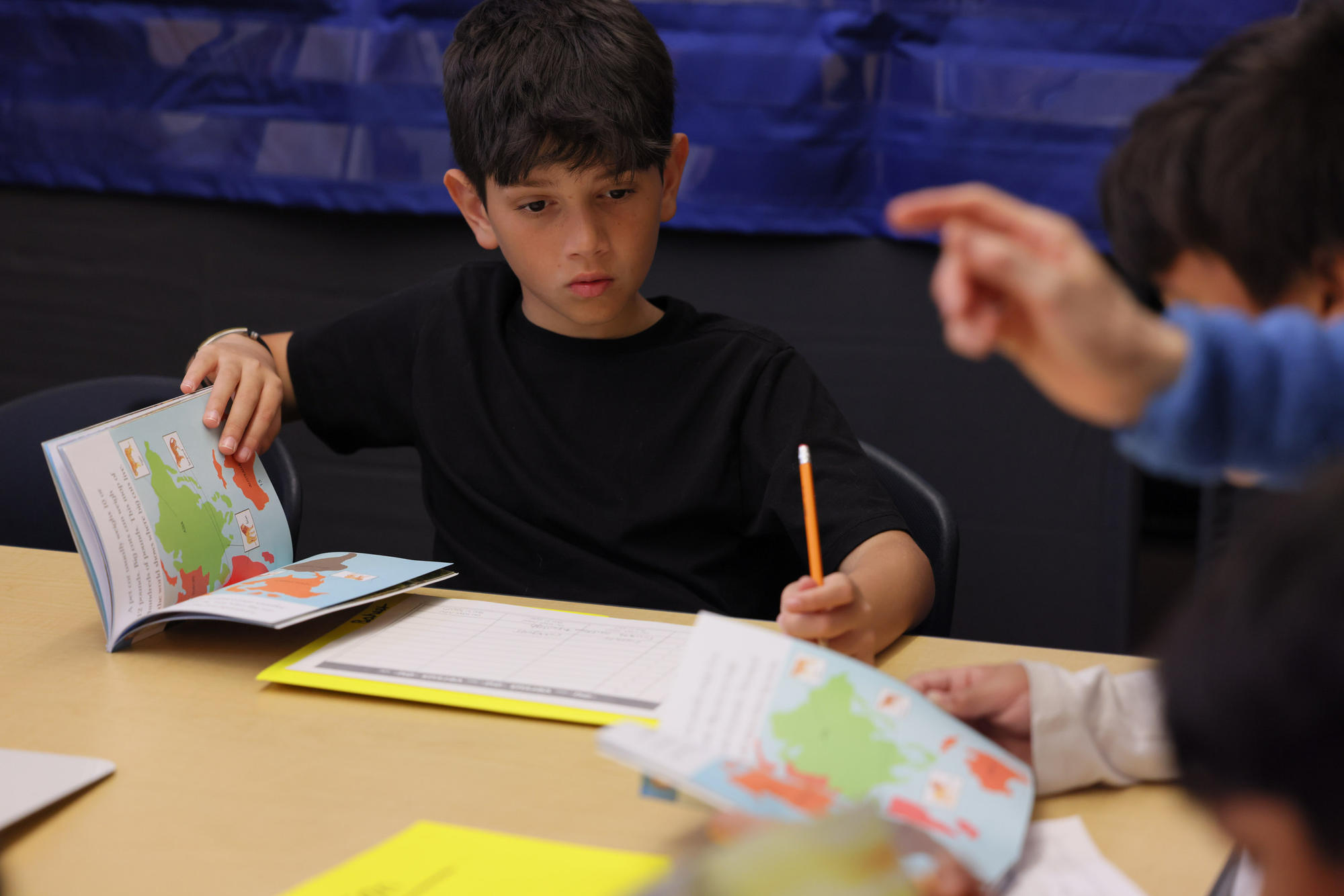

State law requires incoming students to be tested for their English language skills within 10 days of enrollment. Rosann Rankin, Parkside Elementary’s multilingual learning specialist, scrambled to test all of the new Afghan students when they arrived in those first waves. Students are grouped with others at the same English level 45 minutes a day for 20 weeks, where they gain a language foundation.

Parkside now has staff members who were parents of refugee students, or refugees themselves, who can speak Dari and Pashto and assist new arrivals. Since a majority of the incoming immigrant students are from Afghanistan, they pair up as language buddies to help each other outside of class.

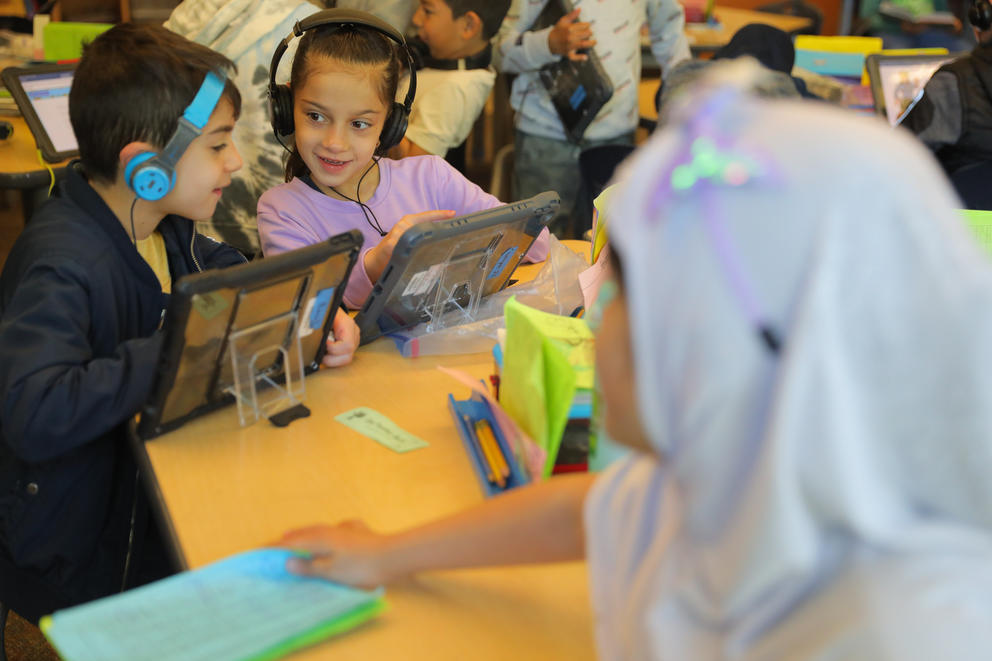

McLaughlin said one of the challenges schools face is accommodating the large number of students arriving at the same time. IRC tripled their funding and increased staffing from 16 to 34 this year, hiring people who were also refugees. The number of students they serve this year has doubled since last year, to 930 students.

Her team has added trauma-informed linguistic support programs to their current student support to help students adjust to their new lives and improve their English.

“Oftentimes these kids, they really just want to go back home. They didn’t choose to come here. America wasn’t a dream for them,” McLaughlin said.

Ahmad said this was the case for his children when they arrived at Parkside. The language barrier was difficult and frustrating for them to overcome.

“I think everything is so different for them. Some of them have never been to school because of either the Taliban and/or COVID,” said Rankin, who also helps teach students English. “Some of them were in private schools in Afghanistan, [and] we have kids from cities and from rural areas.”

Support after school

Sarah Peterson from the state Office of Refugee and Immigrant Assistance said another challenge when it comes to refugee students is providing support outside of academics. At their current capacity, they’re able to provide funding to schools for academic purposes only, not for mental health support or counseling.

School’s Out Washington and Lutheran Community Services Northwest are two organizations offering after-school programs for refugee students. School’s Out Washington is a nonprofit that receives funding from the state to invest in after-school or summer programs for students, including their Refugee School Impact Program. One Lutheran Community Services program, Refugees Northwest, helps students work on their English skills.

Fahmo Abdulle, youth case manager and program coordinator at Refugees Northwest, said Refugees Northwest does not have counselors or mental health professionals with the linguistic and cultural backgrounds to fully understand these students, but they do offer mental and wellness workshops for parents to help them deal with the trauma of escaping their country and coming to the United States. Other refugee organizations offer some mental health support, including Jewish Family Service, which has also worked to resettle Afghan refugees.

A school of several languages

The Hedayee kids now love coming to school to learn from their teachers and hang out with their friends, who come from many different backgrounds.

“Especially Samya, every Friday, she asks me, ‘Is there school tomorrow?’ And on Saturday she asks again, ‘Is there school tomorrow?’ I tell her, take it easy, you will have time to go to school,” Ahmad said.

Samya, 7, wants to become a teacher since she loves using her second grade homework to teach her mother English. Ahmad’s wife asked not to be named because her brother was arrested by the Taliban, and worries for their relatives who are still in Afghanistan.

She is currently taking language classes at Highline Community College. Everyone in the family including their youngest, 4-year-old Sahaba, can now speak, read and write in English and Farsi. Similar to other immigrant families, the children sometimes translate for their mother in everyday life, from talking to a delivery person to making doctor’s appointments.

Bobbi Giammona, principal of Parkside Elementary, said the school encourages students to speak their home language in school just as much as they tell them to speak in English.

“Kids who are bilingual can keep both,” Rankin said. “Their brains can do things that monolingual kids can’t, as well as stay in connection with their grandparents and parents so there’s not a divide in their family of who can and can’t speak.”

Giammona said all staff at Parkside – from classroom teachers to librarians and music teachers – are GLAD-trained (Guided Language Acquisition Design), which allows students to communicate their thoughts in different ways, like drawing or using their home language, if they cannot express themselves fully in English.

The school library also supplies books in several languages to ensure that students keep their native language and read books if they’re not fluent in English yet.

Ahmad and his wife tell their children to write stories in a notebook in Farsi to ensure they don’t forget their native language, since they’re mainly using English in school.

“It’s important for them to remember their language for when we can go back to Afghanistan one day, so they can speak to my mother, their grandmother and all of our family there,” Ahmad said.