Some of George’s days start at 5 a.m. and go until midnight. She’s handed out her personal number to tribal members. To put it lightly, she’s dedicated to the job.

“This isn't just a job, or position. It's definitely work that needs to be done,” George said.

On this Saturday she was in Toppenish, a small town south of Yakima that’s on the Yakama reservation. She was decorating vehicles used for census outreach in underserved tribal neighborhoods throughout the lower Yakima Valley. The Yakama members she met were part of the Yakama-Yakima El Censo Coalition, an organization prioritizing outreach to historically undercounted groups in south-central Washington, focusing on people of color and low-income communities.

While COVID-19 had forced changes to many of the group’s in-person census events and programs, that wasn’t its largest hurdle.

The U.S. census has drastically undercounted Native communities in the past. They were the most underrepresented ethnic group in the 2010 census, with an undercount of almost 5%, compared with 2.1% of Blacks and 1.5% of Hispanics, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

A variety of reasons contributes to a low count, including the tribes’ relationship with the federal government, nontraditional addresses on reservations and a lack of direct outreach to tribal members. But George, alongside other individuals and nonprofits, wanted to change that for 2020.

“This year, our trusted messengers are Native American, Yakama specific. So that’s the big difference, and I think that’s helped a whole lot because of the familiar face,” George said.

Growing up, tribal members have been taught not to answer the door to strangers, and George realized local community members were needed to reach out. While there isn’t a specific amount of dollars lost per person in an undercount — funding formulas are derived from multiple factors — for every 100 households not counted in the 2020 census, the state could lose up to $5.8 million, according to the state Office of Financial Management.

“I think that sometimes people think that this is ‘just census.’ It’s not just census. This is so much more, and it affects us greatly,” George said. “In our clinics, our roads, everything. When I share that with people, then they begin to understand. … Sometimes it's taking six phone calls, 10 phone calls, a whole lot of piles of information, sharing emails, and then finally they understand the importance of it.

Mathew Tomaskin, a Yakama Nation legislative liaison, and Patricia Whitefoot, a Yakama Nation community advocate, chat while their caravan gets ready to drive through tribal housing complexes in Toppenish, Wapato, White Swan and Harrah, on Sept. 26, 2020, in Toppenish, Yakima County. (Emily McCarty/Crosscut)

George organized the caravan on Sept. 26 with two Yakama Nation members, Mathew Tomaskin, a legislative liaison for the Yakama, and Patricia Whitefoot, a devoted community activist and advocate.

Tomaskin started work for the 2020 census over 2½ years ago when he attended a training held by the Yakima Community Foundation. He, along with other organizations representing people of color, formed a Complete Count Committee. These committees work to educate underserved groups through targeted efforts and provide a link between governments, communities and the Census Bureau to achieve a complete count.

Tomaskin was wearing an “I’m Indigenous and I Count” T-shirt on the day the caravan headed out carrying an oversized bag of Halloween candy to throw out as in a mini-parade. In-person events had been planned, but COVID-19 put a halt to all that. The group instead decorated their cars with colorful markers, calling for people to be counted and to complete their census. They had census Frisbees, magnets, face masks and shirts to toss from the cars, careful to keep social distance.

The caravan would drive around for about three hours, Tomaskin estimated, visiting Toppenish, Wapato, White Swan and Harrah, all small cities in the lower Yakima Valley.

“We’re just hoping to bring the awareness around for people to do the census. It only takes 10 minutes,” Tomaskin said. “Our [trusted] messengers, what their task was to find 20 families and encourage those 20 families to do the census. ... If they've completed their tasks, this is just an extra for us to move forward, making sure that everybody gets counted at today’s event.”

During the 2010 census, Tomaskin said, these efforts — raffles, giveaways, caravans — didn’t happen. Having trusted messengers who are from the same tribe is important, Tomaskin said, especially with those with historically poor relations with the federal government.

“Our people, tribal people, we’ve already suffered enough historical trauma,” he said. “There was nobody really pushing people to get counted. … This right here is a change. Look, it's a Saturday; we could be at home. ... But we have a dedicated staff here and we're out here doing this caravan.”

Whitefoot, one of the other caravan organizers, was there alongside her grandchildren. She was involved in the 2010 census and emphasized another important aspect of the effort: legislative redistricting. She works with the Washington State Redistricting Coalition for transparency in redistricting. As a result of the 2010 census, the Yakama Nation was split in two, now a part of both the 14th and 15th legislative districts.

The splitting of the reservation contradicts the intent of the law, Whitefoot said, and other communities have also been splintered, including the Confederated Tribes of the Colville. She pointed to the Colville Tribe as an example, remembering when Colville member Joe Pakootas ran for Congress. Whitefoot said a majority of the Colville tribal members were in another district and Pakootas couldn't receive their votes.

But she does see positive changes since 2010, due in part to the work of the Na’ah Illahee Fund of Seattle. The state Office of Financial Management chose that organization to distribute funds to tribal groups across the state for census outreach.

The Na’ah Illahee Fund, a women-led Indigenous nonprofit that focuses on ecology and food sovereignty to "advance climate and gender justice," became involved in the census several years ago when Executive Director Susan Balbas learned that the 2020 census would be receiving far less outreach money than in 2010, said Samantha Biasca, whose Haida name is K’_alaag’aa Jaat, the group’s grants program officer.

“They just knew that in order to avoid a dramatic undercount of communities of color, the philanthropy world is really going to have to step up into a much bigger role to direct funding towards communities of color to get a complete count,” said Biasca, who is Haida, Tlingit and Inuit.

Biasca said although it may not seem like it at first glance, their census work is related to their mission of environmental justice and giving back to Mother Earth.

“The work that we do, trying to position communities of color and Indigenous women … trying to really lead them into positions of empowerment, starting from youth getting involved in gardening and traditional medicines and herbs — that all is very much so a part of trying to instill from a young age the importance of civic engagement and getting a seat at the table where decisions are being made, getting on boards, getting into politics,” Biasca said.

Na’ah Illahee has worked with community organizations, tribes and families to get Native communities counted in the census, providing grants for those groups to hold events, give away prizes, create census-branded shirts and signs, and recruit tribal members.

Biasca and a friend also created the PNW Natives site, which hosted a virtual canoe race in which Washington tribes competed for the highest census count. A total of $40,000 in cash prizes was awarded.

Coming in first was the Port Gamble S'Klallam tribe, with a 79.6% census self-response rate, which is even better than Washington’s general self-response rate of 72.1%, second best in the country as of Oct. 1.

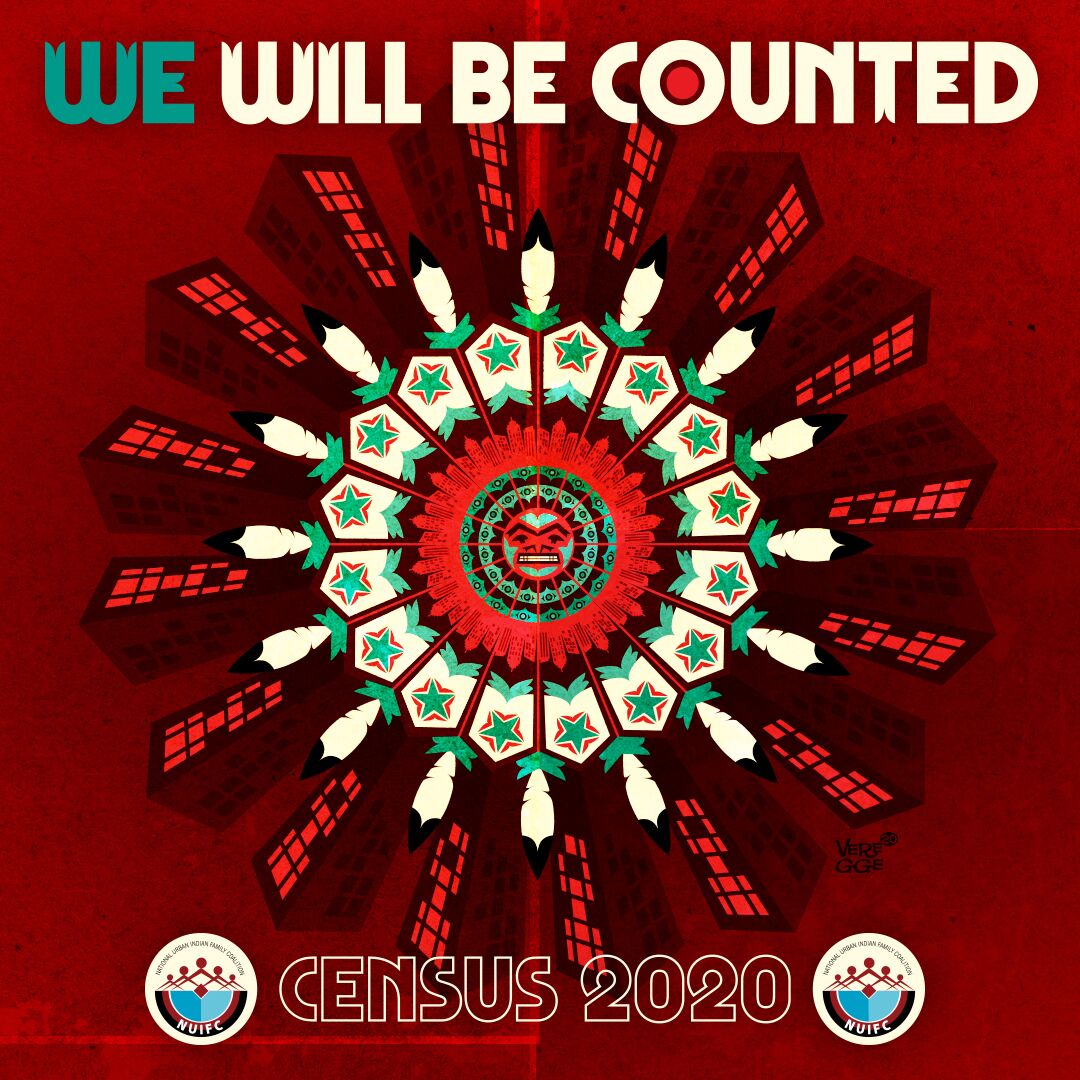

A member of the Port Gamble S'Klallam tribe, Jeffrey Veregge, is using his creative skills as an artist to encourage Native communities to be counted. Known for his “Salish geek” art, he was previously commissioned by Marvel to recreate popular comic covers in his unique formline style for its Indigenous Voices series.

This year, Veregge was commissioned by the National Urban Indian Family Coalition in Seattle, which used his census art in bus ads, billboards, T-shirts and posters in almost 20 cities across the country, from Seattle to Washington, D.C.

Alaina Capoeman, Quinault member and Washington state’s tribal partnership lead with the U.S. Census Bureau, said she’s seen vast improvements from 2010, when she was part of the inaugural census tribal team and worked in Idaho, Oregon and Washington. This year, she’s one of four tribal team workers for Washington alone.

Capoeman connects tribal liaisons with the government to educate people on the census, including operation details, timelines, COVID-19 information, permission to send enumerators on tribal lands and recruiting tribal members.

“For many tribes, they closed their borders [because of COVID-19]. … In some cases, it took tribal resolutions to say the 2020 census is an essential service, we will allow these workers to come out,” said Capoeman, who says the tribes have worked hard this year to educate and get Native people counted.

“I've been really impressed with the tribes’ ability to change and keep in the forefront safety of their communities and just being creative in their outreach and engagement,” Capoeman said. “They’re owning this census and saying, ‘This is ours, it is important for us, and we’re going to stand up and be counted.’ ”