Even under heavy sanctions from the U.S. government, one man in particular stood out. Paul Robeson was defiant and would not be silenced. His resistance took him to the foot of the International Peace Arch in Blaine, Washington, where he staged a series of concerts to deliver a message of peace and equality.

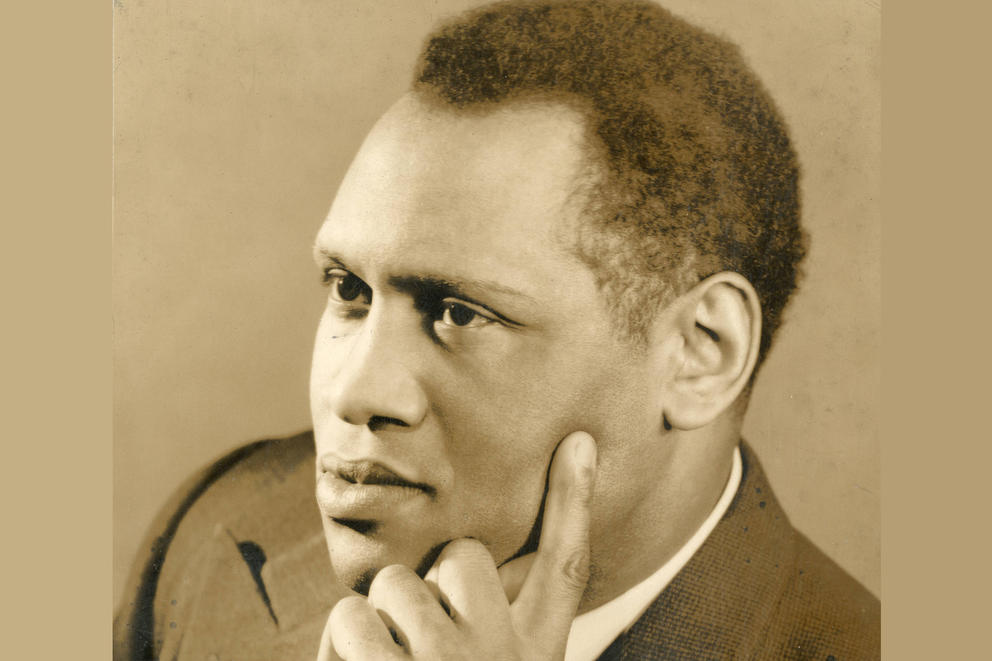

The son of an enslaved father, Robeson was an American phenomenon — one of the best-known Black men of his time, he became an international celebrity. In the 1920s he was a football All-American and academic star at Rutgers University. He later played professional football for one of the NFL's foundational teams, the Milwaukee Badgers. He earned a law degree at Columbia University, but his commanding presence, charisma, and gorgeous bass-baritone voice brought him world fame in the theater, in concert halls and on Hollywood’s silver screen.

He starred in plays, including a production of Shakespeare’s Othello, to rave reviews. He sang “Ol’ Man River” in stage and film versions of the musical Show Boat and helped make it a classic. While he performed, he was also a political activist fighting for civil rights. He was the darling of progressives. He traveled the world singing and speaking on behalf of Black rights and world peace. He spoke out against the Korean War.

As the Cold War took hold in the late 1940s, he went to Europe and spoke at a Soviet-sponsored peace conference, and the American press created a sensation saying that Robeson was a Russian propaganda tool, a “Black Stalin.” The combination of his race and leftist politics became toxic.

His criticism of America on race and foreign policy led the U.S. government to seize his passport so he could not travel abroad. This had a real impact on Robeson, as his international performances were popular. He sang all over the world. But with the travel ban, Robeson’s income from performing dropped from $150,000 per year in 1949 to a mere $3,000. Right-wing agitators attended some of his speaking events and attacked attendees. This created the idea that it was Robeson’s ideas that were unsafe.

He would not be silenced. Robeson jumped at the chance to speak and sing in Vancouver, B.C., when invited to do so by Canada’s International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers in January 1952. But, despite not needing a passport to travel in Canada, he was turned back at the border. The U.S. and Canadian governments had cooperated to keep him out.

Robeson tried again in February, this time accompanied by International Longshore and Warehouse Union head Harry Bridges, a well-known labor activist. Again the party was turned back. The Union protested, saying the United States had become “a prison for any of its citizens who possess ideas that do not meet the approval of the State Department.” Bridges's lawyer compared the U.S.'s tactics to those used by Nazi Germany. Robeson subsequently tried to book Seattle’s Civic Auditorium for a concert, but the city cancelled, citing an ordinance that denied the use of public buildings for events that might incite “racial or religious antagonisms.”

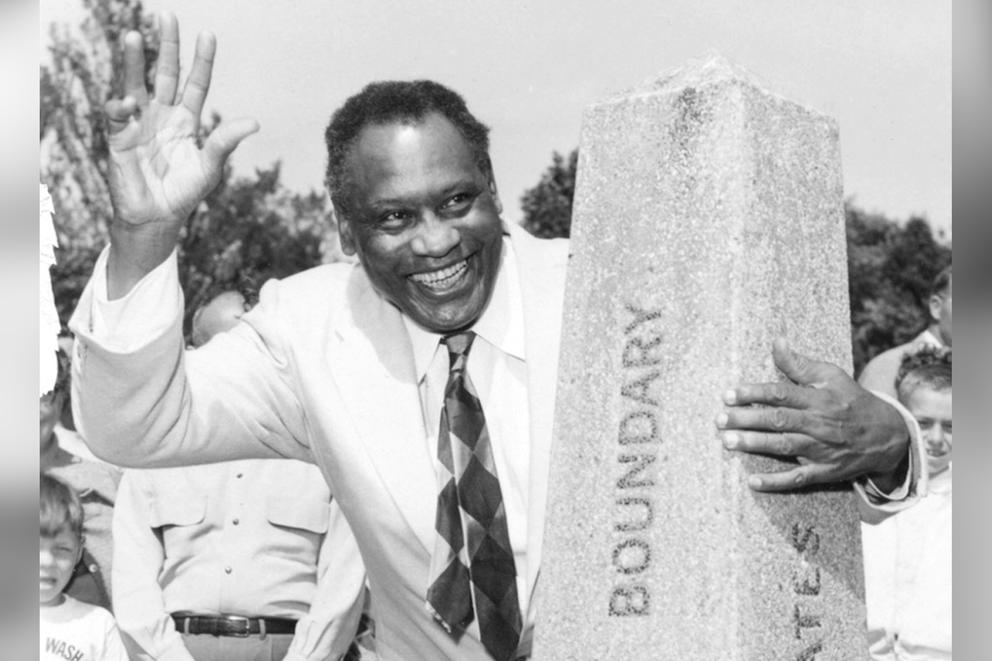

Undeterred, Robeson found the perfect venue. In May, he headed to the border in Blaine with some 30 chartered buses. He parked a flatbed truck on the U.S. side of the Peace Arch from which to speak and give a concert. The FBI and INS expected trouble. Some other Robeson events had attracted right-wing hooligans, but none showed.

Who did show? Some 30,000 people, the vast majority of them on the Canadian side. They created a massive traffic jam that closed the border for a time. Robeson sang “Ol’ Man River,” and also lefty anthems like “Joe Hill,” about a Wobbly union martyr. The event was such a hit that Robeson came back annually for three more Peace Arch concerts, the last in 1955. On the Canadian side, the Arch inscription reads: “Brethren dwelling together in unity,” a message Robeson himself was preaching.

His troubles weren’t over. He was called before the House Un-American Activities committee as a suspected Communist during the witch-hunt years. He refused to say if he was, invoking the Fifth Amendment. He also told the committee: “Gentlemen … you are the un-patriots and you are the un-Americans and ought to be ashamed.”

Robeson eventually won the legal fight to have his passport restored — the Supreme Court having decided that the right to travel was an essential liberty —but he continued to struggle against blacklisting and racial prejudice and his right, as an American, to enjoy equal rights. His stand at the Peace Arch was a major statement for those causes.

It’s perhaps best to end with some of the words Robeson uttered before the crowd from that flatbed truck:

“I want to just say a few words, and to thank you again for your very great kindness in coming here today. It means much to us in America, to Americans struggling for peace in the Northwest. Some of the finest people in the world, under pressure today, facing jail, facing hostile courts for the simple fact that they are struggling for peace, struggling for a decent America where all of us who have helped build that land can live in peace and in good will.”

For more on this story, listen to the Mossback podcast. You can find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon or wherever you get your podcasts.