“In addition to competitive activities such as golf, chess, and soccer, Ms. Padilla-Reyna champions animal welfare,” her website states. “She also volunteers for food pantries and nursing homes.”

But court records filed by government prosecutors tell another story: Over a year and a half, Padilla-Reyna stole nearly $300,000 from a federal COVID-19 relief program meant to rescue struggling businesses from economic collapse.

“The Defendant’s crime required planning, reflection,” prosecutors wrote, “and a disregard for the well-being of others during a time of international crisis.”

As an unpredictable virus filled hospitals and emptied city streets in March 2020, Congress found rare bipartisan agreement on a stimulus plan to bail out business owners forced to shutter their storefronts. The Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) ultimately pumped $800 billion into the economy, a single program as large as the federal government’s entire response to the 2008 financial crisis. Told to prioritize speed, banks passed along billions in PPP and Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL) to many businesses that misused the money or didn’t even exist. Scammers also targeted billions in expanded unemployment payments.

“The idea was, let’s send all the money out … and you all can go chase the money if it gets in the wrong hands,” said Michael Horowitz, chair of the Pandemic Response Accountability Committee (PRAC), a federal oversight board created as part of the stimulus legislation.

U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) prosecutors in local offices around the country have now started that long and complicated chase, bringing criminal charges against more than 2,230 people so far, according to a DOJ spokesperson. In recognition of the immense task before them, the Eastern Washington office in February 2022 formed a “strike force” to expedite the lengthy investigative process typical for fraud cases. Statewide, prosecutors have since indicted 28 people and one company on charges including wire fraud, bank fraud and identity theft. Padilla-Reyna is one of them.

Crosscut reached out to numerous defendants directly and through family members or their lawyers. None were willing to talk on the record. But court documents and other public information offer a glimpse at their lives and what may have motivated their alleged crimes.

Those charged with pandemic fraud in Washington range from a Seattle tech executive to a meth-addicted state employee in Moses Lake. There’s a suspended dentist and a security guard, a baseball ticket hawker and nuclear site contractors. One was a senior state official in Nigeria who commissioned a magazine story about his own philanthropy and was later grabbed by federal agents in a New York airport. Another is a former Spokane cocaine mule who spent 15 years locked up and is now on dialysis for kidney failure.

This story is a part of Crosscut’s WA Recovery Watch, an investigative project tracking federal dollars in Washington state.

Facing what by some estimates could be more than $1 billion in fraud, prosecutors in Washington have charged fewer cases than their counterparts in states like Georgia, but more than some other comparable states. A few defendants have netted up to five-year prison sentences for elaborate identity theft scams. Less ambitious schemers, who pleaded guilty to stealing under $55,000 each, received probation and were ordered to return their ill-gotten loans.

Federal watchdogs such as the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Office of the Inspector General have warned that federal agencies lack sufficient resources to get to the bottom of all the fraud, and President Biden has requested billions more for those efforts. But so far Congress has not addressed those requests.

Who gets charged, and who gets away, may largely come down to decisions made by regional prosecutors in the coming years.

“If you study those periods in history where the government has had to stimulate the economy … you always see a period of robust prosecution that follows it,” said Matthew Adams, an attorney who defends people accused of pandemic relief fraud in New York.

“But we’ve never seen anything this big.”

Chief of Fraud and White Collar Crime Unit Dan Fruchter, with the U.S. Department of Justice COVID-19 Fraud Strike Force, works in his office at the Eastern District of Washington U.S. Attorney’s office in the Thomas S. Foley United States Courthouse, Wednesday, March 22, 2023, in Spokane. (Young Kwak for Crosscut)

Spokane’s ‘Strike Force’

With curved stone peaks jutting from each corner, the Thomas S. Foley U.S. Courthouse in downtown Spokane looms over passersby. The U.S. Attorney’s Office occupies the third floor, from which federal prosecutors can see the city’s waterfalls roaring beneath the nearby Monroe Street Bridge.

In his office, Assistant U.S. Attorney Dan Fruchter keeps more than a dozen piles of neatly stacked papers on a table near his desk. Each pile represents a criminal fraud case or a group of related cases. There’s a pile for the manufacturer that sold tainted juice, an air polluter pile, a doctor-diverting-opioids pile, a civil rights violations pile.

One 6-inch-tall pile rises above the rest. For the past year, Fruchter, who heads the Fraud and White Collar Crime unit, has increasingly turned his attention to recovering unlawful pandemic business loans as part of the office’s COVID-19 Fraud Strike Force.

Vanessa Waldref, U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Washington, launched the strike force early last year to fast-track charging people who had defrauded pandemic relief programs.

“We decided this is going to be a priority for us,” Waldref said, “to show that it’s unacceptable for individuals to take advantage of these funds that were designed to help our communities thrive during a time of incredible crisis.”

In addition to his other cases, Fruchter works as one of four attorneys on the strike force, which also includes four support staff who help investigate, generate leads, procure bank records and seize assets. Such strike forces now operate out of at least six other U.S. Attorney’s offices.

The relief fraud allegations in Fruchter’s case pile vary. Some defendants made up businesses that didn’t exist. Others operated real businesses registered with the state, but lied about having employees or inflated revenues to qualify for bigger loans. And then there were the real business owners with real employees who misused the money for personal purposes.

Some defendants obtained enough money to buy a luxury house, while others’ alleged spoils fulfilled more modest ends – renting an apartment, or paying off medical bills.

In the year since launching the strike force, the office has publicly filed criminal charges against 14 people and one company, altogether involving more than $20 million in loans. Four people have been sentenced thus far, and none have faced prison time – all were put on probation. Three are scheduled for jury trials, and one company settled for nearly $3 million to avoid charges.

By white-collar fraud standards, investigators across government view that as a speedy clip. But in the ocean of fraud enabled by PPP, it’s closer to a drop.

No one knows precisely how much money was stolen. The Government Accountability Office puts the percentage of improper payments around 4% ($36 billion, nationally), but researchers studying PPP at the University of Texas estimate that about 8% of the loans ($64 billion) exhibited suspicious characteristics.

The overwhelming majority of PPP loans have been forgiven – more than 90%, according to an NPR analysis.

What seems certain is that there’s more fraud than prosecutors could ever uncover and pursue, even with near-unlimited resources and time. Businesses in Washington state alone received some $27 billion in pandemic loans, according to the U.S. Attorney’s Office. Even the lower estimate would indicate more than $1 billion of PPP fraud just in Washington.

“Very practically, we don’t have enough resources in our office to do all these cases,” Waldref said. “We had to make some hard choices and really prioritize this.”

Waldref added that she is seeking additional funding from the DOJ to expand COVID-19 fraud prosecutions.

Given the vast, still-unknown scale of potential fraud, Fruchter said the team prioritizes cases based on the amount of actual “loss” as well as the amount sought. Cases involving identity theft also rate highly because if prosecutors can’t prove the fraud, the victim could be on the hook to pay back the money. Recoverable assets make a case more urgent, too: If a defendant used the money to buy a boat or a house, there’s a good chance it can be seized or bank accounts frozen.

Due to the limited fraud preventions on the front end, Fruchter said he sees prosecutions as the only real attempt yet at bringing accountability to a process that allowed scammers to swipe money out of the hands of deserving businesses.

“The folks who are out in the cold for all of this are the folks who had legitimate businesses that weren’t able to participate in these programs because the funding ran out,” Fruchter said. “We view that as an incredibly egregious breach of public trust.”

From left: Assistant U.S. Attorney Tyler Tornabene; Eastern District of Washington U.S. Attorney Vanessa Waldref; Chief of Fraud and White Collar Crime Unit Dan Fruchter; and Special Assistant U.S. Attorney Frieda Zimmerman, all of whom are with the U.S. Department of Justice COVID-19 Fraud Strike Force, pose for a photo in their trial preparation room at the Thomas S. Foley United States Courthouse, Wednesday, March 22, 2023, in Spokane. (Young Kwak for Crosscut)

Pursuing charges

Roshon Thomas lay in bed, plugged into a dialysis machine in the predawn hours of March 17, 2022, a court filing states, when six federal agents entered his apartment in a low-income housing complex near the southern edge of Spokane’s city limits.

The 52-year-old was no stranger to federal law enforcement. By his 20th birthday, he’d already begun amassing multiple felonies for drug distribution. He ran cocaine up and down the West Coast, from California to Spokane in rental cars, his trafficking documented in a case that went to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals and set precedents for the privacy rights of rental-car users.

Thomas spent 15 years locked up. Shortly after his release in 2017, he was diagnosed with end-stage kidney disease. The treatment required nine hours of dialysis every day, according to a sentencing memo submitted by his attorney. He held a few jobs during that time, at Walmart, at a Napa Auto Parts store, as a delivery driver for Instacart and GoPuff.

Early in the pandemic, Thomas had an idea. On July 28, 2020, he applied for a federal relief loan for a custom T-shirt printing business called I’s Design. On his application, he wrote he had started the company a year prior, and that as of January 2020 he had seven employees and $65,000 in annual revenue. In fact, he had applied for a state business license and opened a bank account just four days prior. There were no employees, no receipts. For the company’s address, he listed his apartment, but with “suite” in place of “apartment” number.

About two weeks later, SBA approved his loan and sent him $32,400. He ended up submitting three fraudulent EIDL applications. Though one was denied, he collected just under $55,000. He spent the money on rent, medical bills, and a car, according to a filing by his lawyer.

Prosecutors sought a sentence of eight months’ home detention, citing his extensive criminal history and repeated attempts to scam the loan program. Thomas’ lawyer argued that home detention would interfere with his medical care and his work as a delivery driver, potentially causing him to lose his subsidized apartment. The judge ultimately sided with Thomas, sentencing him to five years’ probation.

Though Thomas’ personal circumstances are unique, his loan is in some ways a typical case for the strike force. His business wasn’t real, and he did not qualify for a PPP loan. The amount of money he swindled was, by federal criminal standards, fairly modest.

The strike force has indicted five people for individual dollar amounts under $55,000, most recently in December 2022.

The continued prosecution of smaller-dollar cases comes amid recent reports that the SBA may decline to collect overdue EIDL loans under $100,000. EIDL loans, unlike PPP, were meant to be repaid.

Adams, a defense attorney with Fox Rothschild in New York City, told Crosscut that before the pandemic, it would be rare for federal prosecutors in his district to bring fraud cases in which the loss is under $100,000. The unprecedented outlays and losses of pandemic relief programs changed that calculation.

“Traditional notions of what would ordinarily be too de minimis to be a federal criminal case have gone out the window,” Adams said. “I’ve got a client that was indicted for under $10,000.”

Adams doesn’t think that’s a bad thing, necessarily – from a taxpayer perspective, he said he sees the value. But he worries that appropriate scrutiny of people who used emergency aid to buy sports cars may overreach to business owners who made honest mistakes based on ambiguous guidance during a chaotic time.

“Of course the person who took a PPP loan and bought a Ferrari should be prosecuted,” Adams said. “But should the company that may have feared, the small business that may have feared whether they were going to be able to survive … and maybe they made some mistakes along the way – should those folks be criminally prosecuted? No, no, not at all.”

“Might they have an obligation to repay some or all of the money that they took? Yes.”

Washington’s approximately 30 indictments lag behind the number in states like Georgia (77) and Florida (63), according to a case tracker maintained by Adams’ firm.

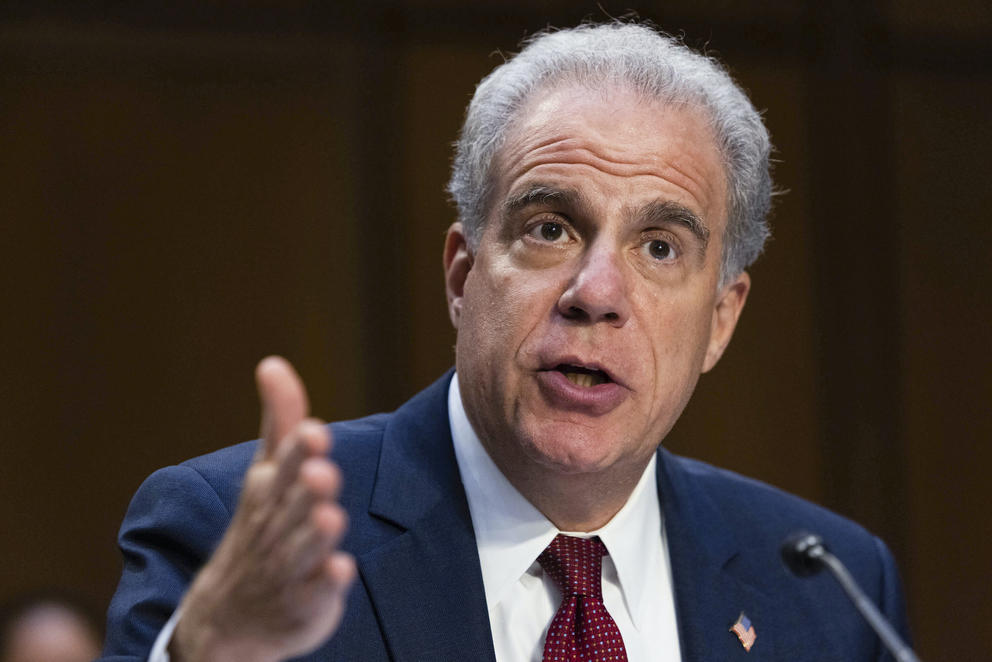

Horowitz, the PRAC Chair, noted that while there are non-prosecutorial tools to retrieve ill-gotten loans – such as administrative recoveries, a civil process done through administrative civil law judges – he doesn’t think any case is too small to be worth prosecuting criminally.

“We don’t want to send the message that crime pays, whether it’s a penny, a dollar, a hundred thousand dollars or a million dollars,” he said. “Yes, we have to make choices. But it doesn’t mean we have to tell the wrongdoers how we’re making the choices.”

Department of Justice Inspector General Michael Horowitz testifies during a Senate Judiciary hearing on Capitol Hill, Sept. 15, 2021, in Washington, D.C. Inspectors general need more authority to go after fraud in the COVID-19 relief programs, said the independent committee overseeing federal pandemic relief spending on Tuesday, May 31, 2022. Committee head Horowitz said the $150,000 threshold is far too low given the scope of the fraud in programs set up to help businesses and people who lost their jobs due to the pandemic. (Graeme Jennings/Pool via AP, File)

Corporate cases

Fruchter said the strike force carefully considers whether each case merits criminal prosecution, and they sometimes opt for civil action against companies instead, but he acknowledged the cases charged so far do not necessarily represent the most extreme examples of PPP fraud. Some are low-hanging fruit that the team could move quickly on. Over time the team has gotten more selective, looking for cases with higher price tags, existing businesses or multiple victims.

“When we first started, we were taking pretty much everything,” Fruchter said. “The idea was, let’s put some points on the board, let’s kinda do a proof of concept.”

One of the larger-dollar strike force cases thus far involves an Arkansas man who allegedly obtained pandemic loans on behalf of others, often taking a 10% cut. An indictment alleges Tyler Andrews steered millions to real and fake businesses in Washington and elsewhere using Social Security numbers and bank information he acquired over email.

Also in the mix are a West Richland man who allegedly bought a house in cash days after his half-million-dollar loan cleared, and a former Wenatchee resident, now at large, who prosecutors say used a $117,000 loan to buy an RV before fleeing to San Francisco.

Most prosecutions do not touch a thornier issue: businesses that obtained relief money but didn’t need it. The definition of “small business” in the first round of PPP funding included businesses with up to 500 employees, or sometimes more depending on the industry. In the mad rush to get money out, businesses owned by celebrities like Tom Brady and Kanye West also collected millions. Some returned the money after public backlash. Others didn’t.

Two other significant cases involved contractors at the Hanford nuclear site in Richland. Two weeks ago, a company called BNL Technical Services and its owner, Wilson Pershing Stevenson III, were indicted for pilfering $1.3 million in PPP loans.

BNL’s employees were paid by the U.S. Department of Energy throughout the pandemic, even when they were waiting on call at home, according to an indictment. Stevenson allegedly used the PPP money to pay off personal debts, prosecutors said, and lied to the SBA about using it to pay his employees.

The case resembles a similar one from last year in which HPM Corporation, another Hanford contractor, agreed to a nearly $3 million settlement to avoid civil and criminal charges.

HPM provided occupational health services to employees at the nuclear site, and when the pandemic hit their contract was actually expanded, The [Spokane] Spokesman-Review reported. Prosecutors allege they pocketed $1.3 million in PPP loans and later lied to the government, saying it was used to pay employees.

As part of the settlement, HPM owner Grover Cleveland Mooers agreed to resign and pay an additional $250,000 fine.

Eastern District of Washington U.S. Attorney Vanessa Waldref, right, speaks with Assistant U.S. Attorney Tyler Tornabene, left; Chief of Fraud and White Collar Crime Unit Dan Fruchter, second from left; and Special Assistant U.S. Attorney Frieda Zimmerman in their trial preparation room at the Thomas S. Foley United States Courthouse, Wednesday, March 22, 2023, in Spokane. (Young Kwak for Crosscut)

Unemployment losses

In spring 2020, as the virus drove people indoors and the economy screeched to a halt, millions of laid-off workers flocked to Washington state’s Employment Security Department (ESD) to collect unemployment benefits. One of the people answering those calls was Reyes De La Cruz, a man in his mid-40s with a boxy face and wispy black hair.

Having worked at the department from 1996 to 2003, De La Cruz was rehired to triage the deluge of calls that had overwhelmed the agency, leading to long delays in payments. Working from his home in Moses Lake, he quickly rose to a specialist role, where he could approve or deny claims.

Court records state De La Cruz used his insider access to steer at least $360,000 in unemployment benefits to himself and others, demanding kickbacks in exchange for approving ineligible claims. He personally shaved off about $130,000 — in some cases by stealing the information of friends and family members to apply for benefits. He’d then direct debit cards to addresses where he’d later intercept them.

“I am doing this and helping you guys get a big amount of money that otherwise would not be obt ainable [sic],” De La Cruz wrote over Facebook Messenger, according to an indictment. “So it should be no problem paying me a small portion for the large amount I am getting you guys.”

Around that same time, jobless claims began pouring in from the email address sandytangy58@gmail.com. The Washington Post reported that the account was linked to Abidemi Rufai, a failed political candidate in Nigeria who was later apprehended by four FBI agents at New York’s JFK Airport as he attempted to check into an international flight. When investigators cracked the email account, they found the personal data of more than 20,000 Americans.

Washington’s unemployment system eventually drew hundreds of thousands of suspect claims, resulting in the loss of at least $647 million to scammers. At one point officials shut down the system for three days to get a handle on the losses. The state has since recovered more than $370 million of the stolen payments.

More than a year passed before investigators charged De La Cruz, in September 2021, with wire fraud, bribery and aggravated identity theft. During his work at ESD, he had also been under supervision following a felony harassment conviction involving an ex-girlfriend.

In a handwritten letter to the judge written prior to sentencing, De La Cruz traced his crimes back to a “life of poverty and constant parental drug and alcohol abuse, violence and fear.” He described physical abuses as a child and severe hazing during his brief service in the Marine Corps. By 2020 he was getting heavily into heroin and methamphetamines.

“I have lived most of my adult life suppressing the memories and immoral activities from my past,” he wrote in the letter, which appears as a faded photocopy in court records. “In my eyes, I was worthless and going nowhere.”

Prosecutors portrayed the case as an extreme example of a government employee abusing his power to enrich himself during a time of national economic disaster. De La Cruz pleaded guilty and was sentenced last September to five years in prison.

Complex crimes

Federal prosecutors in Seattle haven’t created a specific “strike force,” but their cases have often proven more complex than individual fraud schemes, spanning multiple continents and thousands of victims. A recent indictment of two Nigerian citizens involved $2.4 million in losses. Seattle prosecutors also take on the majority of cases involving fraud against state-level agencies based in Olympia.

“In all the cases, there’s at least one particularly egregious fact that — even amongst the ones we charge — separate them from another,” said Cindy Chang, Assistant U.S. Attorney in the Seattle office.

Chang joined the office in March 2021 to focus exclusively on pandemic relief fraud, a task she shares with attorney Seth Wilkinson, who supervises the office’s complex crimes unit.

The two told Crosscut they decided early on to zero in on the most sophisticated perpetrators who stole the most money and filed the most claims – and therefore the most likely to result in substantial prison sentences. In their view, putting a few high-profile people behind bars sends a louder message than indicting dozens of cases that lead only to restitution and probation.

“We just think those people are a lot more culpable, they caused a lot of the damage and benefited a lot more,” Wilkinson said. “Every prosecutor in this office could spend all their time prosecuting people for $20,000, $15,000 loss cases – and that wouldn’t be the best use of our time.”

Many investigations grew out of what Wilkinson described as the “singular” nature of attacks on the state’s unemployment system. Those schemes often enlisted networks of “money mules,” middlemen who, perhaps unwittingly, forwarded fraud proceeds up the chain.

They’ve also pursued several PPP cases in which applicants sought anywhere between a half million and $5.5 million.

Another reason to prioritize the trickier cases, Wilkinson said, is that the state or counties can prosecute the smaller ones – but likely don’t have the bandwidth to get foreigners like Rufai into custody. And those international cases are crucial for deterrence, Wilkinson said, because those scammers thought they were untouchable.

“They previously thought they were operating with impunity, that they could just sit in Nigeria and file all these claims and nothing would happen,” Wilkinson said. “And so hopefully we made a good contribution toward sending that message that that’s not true.”

Joseph Freeman rented this one-room office for five years until in May 2022 the building’s management evicted him for not paying his rent. Freeman was by then under investigation for $640,000 in PPP loans he received for two existing businesses, Special Delivery LLC and New Jack Trucking LLC. (Amanda Snyder/Crosscut)

The scam next door

A four-story red brick building sits along Occidental Avenue in the shadow of Seattle’s Lumen Field. The street is lined with sports merchandise stores, a few bars and food carts selling hot dogs. For five years, Joseph Freeman rented a one-room office on the second floor until the building’s management evicted him in May 2022, an employee said. Freeman was by then under investigation for $640,000 in PPP loans he received for two existing businesses, Special Delivery LLC and New Jack Trucking LLC.

Freeman pleaded guilty to doctoring IRS tax forms to make it appear that his businesses employed 25 people, later sharing the proceeds with unnamed co-conspirators. His lawyer declined to comment, citing a pending May 16 sentencing date.

Crosscut visited Freeman’s former office, known as the Squire Center, on a recent weekday morning. The building’s front desk worker said she remembered him well.

Freeman bought and sold sports tickets, the woman said. Two other ticket-selling businesses rented space in the building pre-COVID; both have since left. In his office, he’d watch sports on big-screen monitors. The room, 201A, is one of the cheaper ones in the building.

She remembered him as kind – one of her favorite tenants, actually. “Joe was really friendly,” she said. “He was into sports … it seemed like he was legitimately running a sports [ticket] broker business.” She recalled he’d struggled to pay his rent toward the end, and made his last two payments in cash.

A nearby hot dog vendor recalled Freeman, saying they used to drink beer together in a nearby bar. He said he didn’t think Freeman would commit fraud.

The front desk worker at the office building seemed disappointed when she heard that the former tenant she was so fond of had pleaded guilty to fraud. When she heard the amount he’d obtained, she gasped.

“That’s not right,” she said.

‘The long haul’

Back in the Spokane office, Fruchter and a fellow strike force attorney returned from a coffee break to find a printed-out cellphone photo resting on a conference table. Snapped moments earlier, it shows the attorneys walking down the street. Seen from afar, the pixelated quality of the photo made the pair look like anonymous suits – Secret Service agents perhaps, or bodyguards.

The two regarded the photo with amusement, turning it around. They suspected a mischievous former colleague who now does defense work. The photo’s caption warned: “Big Brother is always watching.”

Congress voted in 2022 to extend the statute of limitations on fraud related to PPP and EIDL from five years to 10. PRAC has called for a similar extension on unemployment fraud.

Fruchter said he expects the office to continue their emphasis on PPP for another year at least, maybe a few more. But in his experience, other crises are likely to intervene between now and 2030.

“I started prosecuting during the [2008] mortgage fraud crisis, and so those cases were just calling out for somebody to do something about this as quickly as possible. And before that ended, we were in the opioid crisis,” Fruchter said. “I guess in a way, if in 2030 there’s not a new crisis that’s overtaken us, that would be a good thing.”

Prosecutions for PPP fraud have overwhelmingly focused on individuals who scammed the system. But congressional investigations have highlighted the role that banks and “fintech” companies played in rubber-stamping fraudulent applications, making billions in fees off loans while neglecting to take the most basic steps to prevent fraud.

Find tools and resources in Crosscut’s Follow the Funds guide to track down federal recovery spending in your community.

A recent PRAC report revealed that lenders paid out more than $5 billion to businesses with suspect Social Security numbers that don’t match existing records, and applications were not checked against the Treasury Department’s “Do Not Pay” list.

Banks are starting to face scrutiny from the DOJ as well. In September 2022, a bank in Texas was fined $18,000 for approving a PPP loan to a business owner it knew was currently under criminal investigation. The bank earned a 5% fee on the loan, which amounted to about $10,000. Prosecutors in Texas said they believed it was the first time the government had charged a lender with civil penalties for negligent oversight of PPP money.

And in January 2023, the Federal Reserve Board fined a bank $2.3 million for approving six PPP loans the bank knew indicated signs of fraud.

“It may well be that we end up with over, and maybe well over, $100 billion in fraud at the end of the day,” said Horowitz, the PRAC chair. “We’re in for the long haul.”

Awaiting sentencing

State business records indicate that Padilla-Reyna ran her Yakima insurance business out of a tiny gray-green cottage wedged between a Red Lobster and a Mexican restaurant with a mural of a jumping dolphin. Prosecutors charged her last year with submitting 12 false relief applications for business loans to KRP Insurance, KPR Crop and Farm Insurance, and Queen B Collectibles — the former two registered to the gray-green cottage, the latter to a residence in a rural area north of a Yakima suburb.

One of her business registrations also lists her husband — a detective with the Yakima County Sheriff’s Office — as a governing agent. He did not respond to a request for comment.

Padilla-Reyna pleaded guilty in July 2022 to lying to lenders about using loan proceeds to pay nonexistent Queen B employees. Her attorney declined to comment on the case.

Prosecutors are asking the judge for a 21-month prison term. Court records indicate she may also have to forfeit assets to repay more than $300,000 in losses. Her sentencing hearing is scheduled for May 16.

Listen to reporter Brandon Block discuss this story on the Crosscut Reports podcast: