When she arrived in Wisconsin, Knox says, she “could smell smoke in the air,” with particles from more than a thousand miles away sprinkling the Midwest. “That smoke from our fires had drifted across Canada and the northern part of the States, and it was now hitting southwestern Wisconsin,” she recalls. She says she felt like she had “no escape.”

Knox, a retired physician, had treated scores of patients who faced respiratory agitation during wildfire seasons in the Northwest. She battles asthma herself. Just the year before, she had been hospitalized for a week after incessant smoke from Canadian wildfires inundated Washington.

Worried about what the smoke might do to her lungs and her aging father, the two stayed inside. Knox put the air conditioning on the recirculate setting to get fine particles out, and then she asked the director of her dad’s assisted living facility to alert residents unaccustomed to the risk. “It did make the evening news that night,” she says. “Warnings were put out: ‘Anybody over 65 and anyone with any kind of lung problems are encouraged just to stay inside.’ ”

Ask us questions about your health and wildfire smoke at the bottom of this story, or click here.

As wildfires become more common across the U.S., with singed acreage from Washington’s Cascades to Florida’s Everglades becoming an annual occurrence, communities that don’t even see fire may still face an onslaught of smoke.

Places like the Midwest, located between wildfire hotspots in the West, Southeast and Canada, “have a lot of exposure,” says David Molitor, an assistant professor of finance at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. A light dusting of smoke “can make for beautiful sunsets here in Illinois,” he says. “On occasion you can smell it in the air, and see it, but a lot of days it’s imperceptible.”

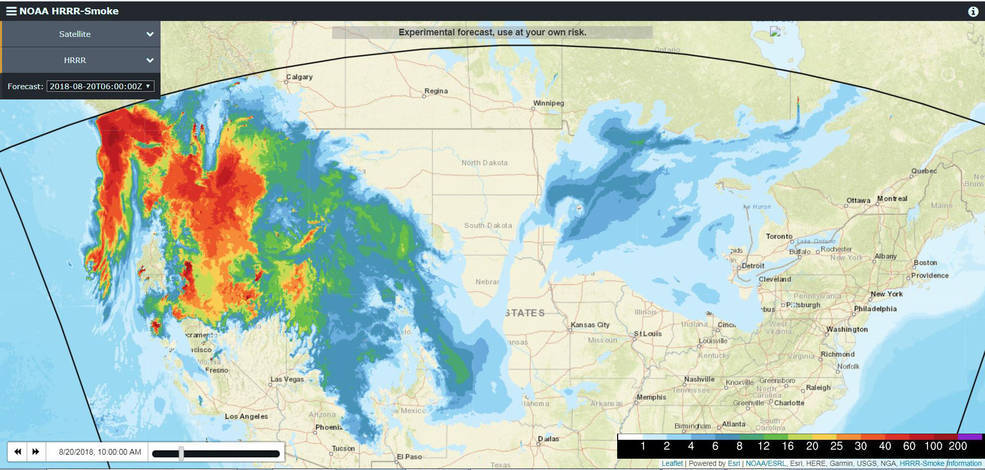

But that doesn’t mean it’s not harmful. Molitor explains that wildfires account for one-fifth of fine particulate matter across the U.S., with wind able to transport smoke for thousands of miles. In fact, this summer’s Western wildfires sent microscopic toxic particles clear across the continent, according to NASA. And just last week, University of Washington researchers in a preliminary report estimated that the smoke incursions in Washington this year killed between 74 and 107 people per week.

In a forthcoming study, Molitor and other researchers estimate that nearly every American is exposed to wildfire smoke each year, even if they never come close to a fire. That may reduce workers’ productivity around the country, resulting in losses of $93 billion annually.

A different study estimates that the cost of premature deaths plus illness from wildfire smoke exposure throughout the nation from 2008 to 2012 totaled hundreds of billions of dollars, with the largest impact in the West and Southeast. Black and to a lesser extent Asian communities were disproportionately impacted. And figures may be rising. One study estimates that smoke-related costs linked to increased illness and early death rose 2,292% in the Western U.S. from 2005 to 2015. The reason is simple: Wildfires and wildfire smoke are increasing.

But Molitor’s study suggests that economic costs may trump health costs. He and his colleagues looked at satellite images to see where smoke travels, pairing that with pollution monitoring data to see what air quality is like during wildfires. They then compared both with productivity and employment figures and found that smoke exposure is responsible for an estimated average of 1.5% in reduced income each year. Older folks who are less likely to be able to work full, productive days during smoke, and those in economically disadvantaged and urban areas, are likely to see even greater reductions.

InvestigateWest is a Seattle-based nonprofit newsroom producing journalism for the common good. Learn more and sign up to receive alerts about future stories here.

Those figures are a small part of an increasingly large bill demanded by a warming planet. A 2017 study published in Science estimates that changes in everything from agriculture to crime to productivity will push America’s gross domestic product down by 1.2% for each degree Celsius rise in temperature.

America’s poorest counties, particularly those in the South and Midwest, will be hit hardest as weather becomes more extreme — colder at some times, hotter at others, with more frequent and violent storms and hurricanes. Without robust local economies that can help to soften these shocks, some counties are poised to see up to a 20% reduction in income under business-as-usual emissions. The authors note, “Because losses are largest in regions that are already poorer on average, climate change tends to increase preexisting inequality in the United States.”

Even though the West Coast is expected to see more fires, it may actually be insulated from the most negative changes. The Northwest, in particular, is expected to actually see some gains in life expectancy and agriculture as the region warms, reducing cold-related deaths and increasing growing seasons.

That doesn’t mean the West Coast won’t have plenty to deal with. In the wake of raging fires, most news headlines focus on short-term fire-related costs, like the $153 million Washington state spends annually just to put out fires (a bill that’s likely to increase, given this year’s unprecedented fire season). That’s not to mention the billions of dollars in damage seen in California, the West’s wildfire hotspot, just last year, a figure very likely to be trumped by this year’s fire season, the worst in history.

But that’s just the start.

Those firefighting and property damage costs don’t account for “impacts to watersheds, ecosystems, infrastructure, businesses, individuals and the local and national economy,” according to the Western Forestry Leadership Coalition, a coalition of state and federal governments.

They suggest that a more accurate bill should include property losses, flooding, a dip in tourism and many other factors. In 2010 — even before this decade of catastrophic wildfires — the coalition estimated that “the true costs of wildfire are shown to be far greater than the costs usually reported to the public, anywhere from 2 to 30 times the more commonly reported suppression costs.” For example, the Canyon Ferry Complex fire, which hit Montana in 2000, cost $9.5 million to suppress, but rehabilitation costs then totaled $8 million. The same year, the Cerro Grande fire tore through New Mexico, burning over 40,000 acres, destroying 260 homes and leading to the evacuation of 18,000 people. Only $33.5 million — or 3% of the total cost of $970 million — was spent on actually putting out the fire.

(NASA)

To stem such unexpected — and rising — costs, the Western Forestry Leadership Coalition recommends viewing active forest management in the same way you would “invest in one’s own preventative care. Upfront costs can be imposing, and while the benefits may seem uncertain, good health results in cost savings that benefit the individual, family, and society.” Preventive actions like removing dead and diseased trees and conducting prescribed burns can clear out badly overgrown forests, which have been spawned by a century’s worth of aggressive firefighting that has helped lead to larger, more catastrophic wildfires.

Some government officials are pushing for more proactive approaches. Last year, Hilary Franz, Washington’s public lands commissioner, asked for an unprecedented $55 million in a dedicated fund to fight and prevent wildfire. That would be paid for by a 0.52% increase in property and casualty insurance premiums, or approximately $5 for every $1,000 in property insurance premiums.

Franz, who is elected statewide to head the Washington Department of Natural Resources, wanted to use the money to double the state’s firefighting force and support 2.7 million acres of forest in poor health. In pitching the proposal, she stressed that one way or another, Washingtonians will have a large bill to pay. “The question is whether we’re going to pay to react, or we’re going to pay to be proactive, protect our communities, protect our landscapes and protect our firefighters.”

The proposal, which was put forward by Democratic senators, was never voted on in the Senate and not considered in the House. It was the second year in a row Franz was unable to push through such a provision.

And it turns out, she was right: Washingtonians did have a large bill to pay. In 2019, the state spent $114.3 million suppressing wildfires.

Without extra staff, Washington’s wildland firefighting force is increasingly overstretched, regularly tasked with fighting fires on both the west and east sides of the Cascades and supporting other states also faced with limited resources. Earlier this summer, Washingtonians supported California’s firefighters, who were “running on fumes” as they battled one of the largest fires in the state’s history.

Molitor says the total costs of wildfires, including hospitalizations, an anemic tourism industry and depressed economic productivity, should make proposals like Franz’s more appealing.

“The regulations are costly, but you make some of that back,” Molitor says, pointing to another study showing that a reduction in all fine particulate matter — all pollution, in other words, not just from wildfires — has saved tens of billions of dollars. And because wildfire smoke impacts everyone in America, with damage not confined to areas that are burning, “even people who don’t live in California or Washington should care about wildfire management,” says Molitor.

“Wildfires aren’t important just because of the areas that they burn, but because of the smoke they produce,” he said. “This is a national issue, not just a West Coast issue.”

Sally Deneen contributed to this report.