Until recently, Misanes’ catch would leave the Lummi Reservation, home to one of the original peoples inhabiting this section of Washington coastline. The seafood traditionally eaten by tribal members headed toward California or China where higher prices could be fetched. But this fall, some of Misanes’ salmon haul has stayed on the reservation, feeding neighbors as part of a pilot program that’s adding locally sourced food to the tribe’s food assistance program.

It’s part of a larger push to give more control to tribes over the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations, the main food assistance program used in Indian Country. Historically, it’s been left to the U.S. Department of Agriculture to truck in items that come from mostly large industrial and retail operations hundreds of miles away for the commodity boxes passed out by tribal food assistance programs.

The Lummi Tribe is one of eight nations participating in the 638 Authority demonstration projects that’s shifting the selection and procurement of foods for the commodity boxes away from the federal government. Created by Congress in 1975 under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, 638 Authority is a legal tool that allows tribes power over federal programs — not only food assistance, but also health care, law enforcement and education. Congress allocated $3.5 million for the food demonstration projects, which began launching in late 2021.

Food sovereignty is important to the health and well-being of the Lummi Nation, said Billy Metteba, the manager of the tribe’s demonstration program. Like many others, he grew up eating very little seafood, historically a mainstay of the tribe.

“It was something that I was not exposed to. I grew up exposed to McDonald's, Dairy Queen,” Metteba said. “The further we get from our cultural values, the further we get from who we are.”

Shifting the authority of food assistance programs allows Indigenous nations to prioritize traditional foods: items that are grown, gathered and processed according to cultural values. It should also help to insulate tribes against supply-chain disruptions like those experienced during the pandemic.

As COVID-19 raged, nations saw the need for food sovereignty amplified to counter what they saw as an apathetic response by the federal government to tribal hunger.

“Tribal leaders and Indigenous people have known since colonization, which forcibly removed people from their food systems, that there was a problem,” said Erin Parker, executive director of the Indigenous Food & Agriculture Initiative at the University of Arkansas School of Law. “Tribal leaders have been working since that time using their sovereignty to repair that food system and revitalize Indigenous food systems in connection to traditional foods, but also just healthy food in general.”

The USDA doesn’t offer a comprehensive measure of food insecurity data in Native populations. Instead it clumps Indian Country in with the “other non-Hispanic category.” The hunger-relief organization Feeding America estimates one in four Indigenous people are food-insecure, compared to one in eight Americans overall. And the pandemic likely exacerbated these numbers.

More of the same

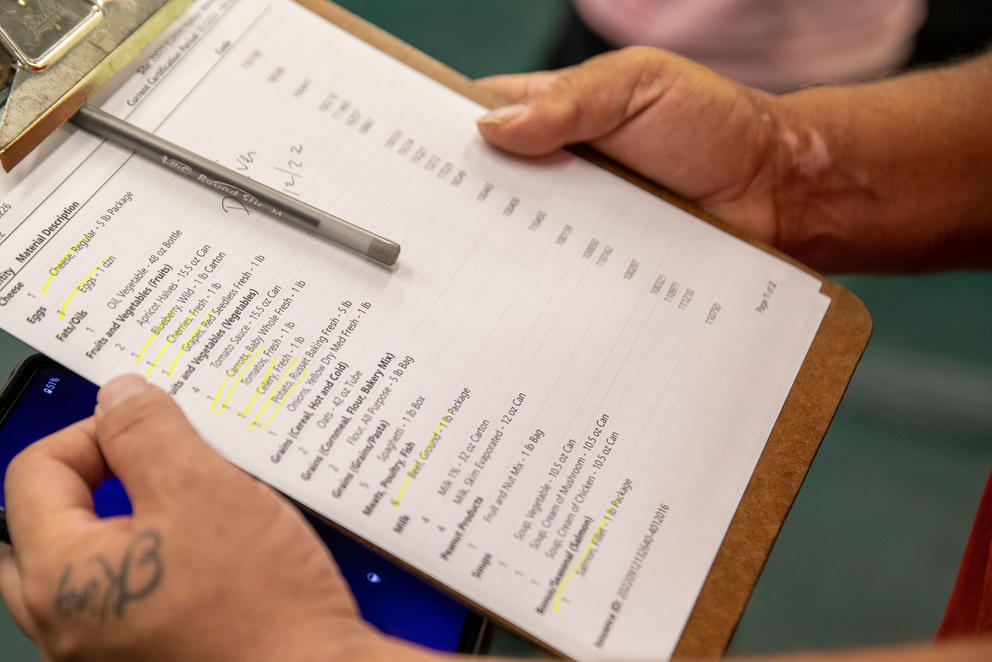

Each month a truck rolls up to the Lummi Community Services building and drops off USDA items for the Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations’ commodity boxes. Cases of canned and dry goods stacked nearly to the ceiling line one side of the warehouse on the north end of the reservation just west of Bellingham. Fresh food gets stashed in the cooler in the other half of the building. Meticulously running through lists from each household, workers pack boxes.

The USDA started the tribal commodity food boxes program in 1977 as an answer to the long distance many living on reservations faced to reach a grocery store. While intended to be a supplemental food program, the assistance program is the sole or primary source of food for nearly 40% of participating households, according to a 2016 government study.

Pre-pandemic, the program served between 80,000 and 90,000 families nationwide. Over the years, the program has faced scrutiny over the quality, nutritional value and cultural relevance of the food.

The commodity program has come far in the last 20 years — it’s no longer unlabeled cans of food, said Dewey Solomon Jr., who helps run the commodity box program for the Lummi Tribe. “But typically it’s been the same things month to month.”

And it’s the same list for every tribe across the nation participating in the food program. The handful of traditional foods available from the USDA include walleye, catfish, bison and wild rice — items not traditionally eaten by the Lummi Tribe. The only traditional food available that’s historically been eaten in Washington’s northwest corner is salmon, which comes from hundreds of miles away off the coast of Alaska.

Clients on the Lummi Reservation tend to skip the walleye and catfish options. But those fish are very much desired inland.

This fall a new local option was added to the list of items available for Lummi households: three-pound sockeye salmon filets caught just a few miles away by Lummi fishermen — the first of many local foods the tribe hopes to add to the commodity boxes.

“I honestly believe, once word gets out, it’s going to be a hot item,” said Solomon as he packed a commodity box. “People are going to ask how many can I get?”

The 2018 Farm Bill allocated funding for a handful of 638 Authority demonstration pilots. Tribal leaders are pushing to broaden the program and secure funding in the 2023 Farm Bill to allow all tribes to tap into local farmers, fishermen and producers to add local items to their food assistance program.

This authority would enable tribes to provide services in a way that’s really tailored to the needs of a particular tribal community and its citizens, said Sandy Martini, a member of the Cherokee Tribe and associate CEO of the Native American Agriculture Fund, a private trust funded by a settlement from a discrimination lawsuit brought by Native American farmers against the USDA.

“It could be a really powerful tool in the hands of tribal leaders,” Martini added. “It’s also an answer to insulating tribes against future supply chain issues. Because local is local, you don’t have to truck it anywhere; everything can break and the food is still there, and they can still figure out how to get it to their community.”

Pushing for parity

Though viewed as a sister program of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, also known as SNAP, which saw an immediate boost from COVID relief funding, emergency allotments were much slower to reach recipients of the tribal commodity boxes. It wasn’t until mid-July 2020 that the USDA announced an expansion for the food assistance program used on Indian Country. And it took another six months — nearly a year into the pandemic — for the additional food to begin showing up.

The tribal commodity box food assistance program was one of the last, if not the last, to receive its CARES Act funding, found the 2022 report “Reimagining Hunger Responses in Times of Crisis,” which was put together by the Native American Agriculture Fund, the Food Research & Action Center and the Indigenous Food and Agriculture Initiative.

“Oftentimes because we’re in these smaller communities, or in rural America, we don't carry a big voting body, we get dismissed or forgotten,” said Toni Stanger-McLaughlin, a citizen of the Colville Confederated Tribes and CEO of the Native American Agriculture Fund. “We are at the end of the line often, even in federal funding.”

The CARES-funded food packages were initially expected to begin in October 2020 for the commodity boxes, said Jalil Isa, a spokesperson for the USDA. However, that was pushed back due to feedback from program operators “on the implementation plan and reporting requirements,” Isa said.

“Tribal leaders had to push for parity with SNAP,” said Mary Greene-Trottier, a member of the Spirit Lake Tribe in North Dakota and president of the National Association of Food Distribution Programs on Indian Reservations, an advocacy group made up of a coalition of tribes.

And when the additional food finally reached the commodity boxes, they weren’t the items Greene-Trottier had hoped for. She wanted to see more variety and traditional items included, like yeast or spices to make the food box more complete, instead of more of the same. Because of this and the extensive amount of work it took to add the items, many tribes did not participate, said Greene-Trottier.

The pilot project has changed all that for the Lummi Tribe. In his first purchase, Billy Metteba, the manager of the program, bought 5,000 pounds of salmon. A second purchase happened a few weeks later, after local fishermen had no place to sell their catch.

“If you can control the market, you can increase the livelihoods of the fishermen while also feeding the community,” said Metteba.

For his next project, Metteba wants to add a live tank to the Lummi Food Distribution Center so crab can be added to commodity boxes. And perhaps eventually the boxes could include deer and elk, other traditionally eaten foods.

“It’s bringing a sense of pride, and it’s very fulfilling for these elders to see these traditional foods, instead of chicken and beef,” added Metteba.

Back on Lummi Bay, Misanes, the local fisherman, watches a hungry seal’s head bob in the waves, happy to monitor Misanes’ net for a snack.

“Our local grocery store is here,” said Misanes, gesturing to the waters off the Lummi Reservation. “We don’t realize how rich we are with the seafood out here.”

This story was produced for InvestigateWest on Dec. 7, 2022 and is republished here with permission. InvestigateWest is an independent news nonprofit dedicated to investigative journalism in the Pacific Northwest. Visit invw.org/newsletters to sign up for weekly updates.