OLYMPIA — Whose voice should count most in legal decisions about the future of kids removed from their homes because of suspected abuse or neglect?

Various factions of grown-ups — birth parents whose children have been removed by Child Protective Services, relatives who take many of those children into their homes, and licensed foster parents — all want their say. All insist they have children’s best interest at heart. The problem is, they sometimes disagree about who is best suited to care for those children.

Those power struggles among well-meaning adults are coming to a head in Olympia as an energized cadre of foster parents pushes for new rights and recognition.

Feeling disrespected and disregarded by the state, many foster parents in recent years have simply dropped out. The resulting shortage of foster homes has left the state scrambling to house the children in its care, warehousing hundreds of them in hotels and even state offices.

In a first-of-its-kind rally, more than 100 foster and adoptive parents — many with kids in tow — gathered on the steps of the Capitol earlier this month to ask lawmakers to give more weight to the strong bonds they develop with the youth in their care.

"We can change the foster care culture to one of respect, honesty and honor,” Yakima foster mom Shannon Love told rally-goers wrapped in teal tartan scarves and hats embroidered with the words “raising hope.”

The foster parents were excited about legislation that would have directed judges to consider children’s attachment to long-term foster parents when deciding whether to move a child into a relative’s care instead. Within days of their rally, though, the foster parents saw their hopes dashed when a key legislator — Rep. Ruth Kagi, D-Seattle — decided to stop advocating for the contentious bill.

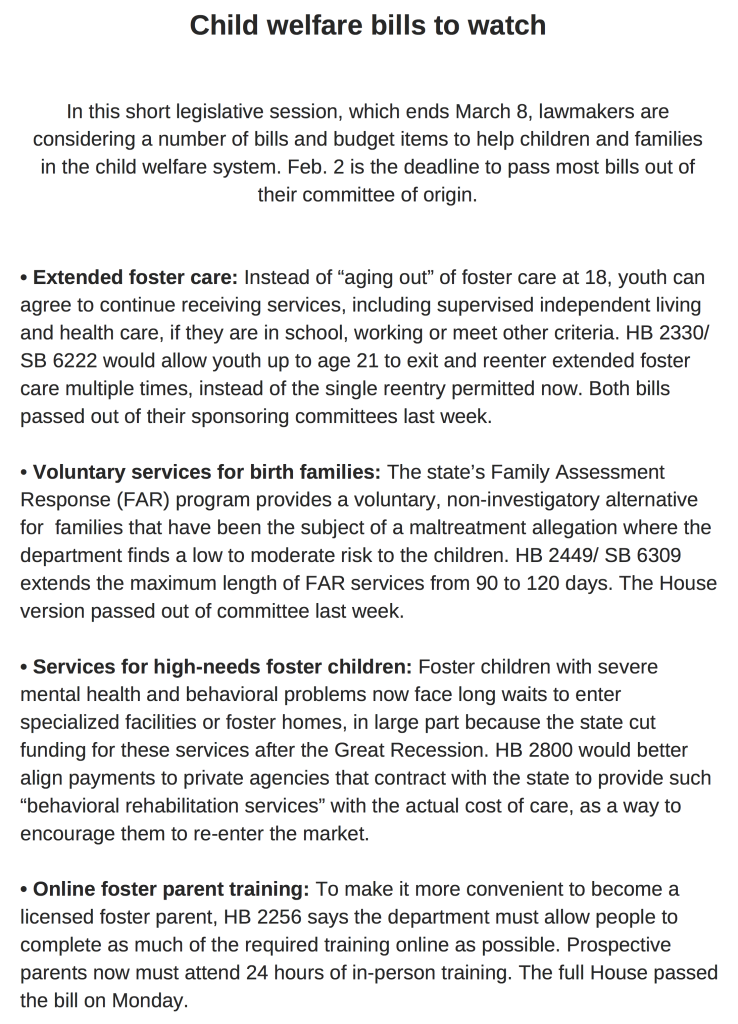

The 2018 legislative session still could see passage of several bills that aim to improve the state’s ailing child welfare system for kids, birth families and foster parents, including bills that would:

• Make it more convenient to get foster parent training (HB 2256)

• Increase facilities and foster homes for children with severe mental health and behavioral problems (HB 2800)

• Extend the timeline for birth parents to receive voluntary assistance, such as help with family bills, treatment for addiction and other services, when the state deems that their children are not at severe risk of harm if left in the home (HB 2449/SB 6309)

Despite their legislative setback, foster parent advocates say they are not giving up.

“We will all be heard if we stand together,” said Jessica Hanna, president of Fostering Change and a foster and adoptive mom of 11 years. “We are trying to unify as many voices as possible.”

That includes the voices of birth families, Hanna says.

Hanna and other central Washington foster parents formed Fostering Change about a year ago to help fix a child welfare system she says traumatizes everyone involved. The group organized last week’s Olympia rally, which drew foster parents from as far away as Spokane, Goldendale and Mount Vernon.

One of the foster parents’ main concerns is that infants and young children often live with a foster family for years before the state finds a relative willing to take them. Because state law gives preference to placing children with kin, the state typically sends children to live with that relative, even if the person had no previous relationship with the youngster.

Especially when relatives live in another state, that transition is sometimes done without giving children time to get to know their new caregivers. "We are all about just reducing as much trauma for these children as possible," Hanna said.

Those sudden, heart-wrenching partings are a key reason foster parents say they leave the system. The state today has about 5,000 foster homes — nearly 1,000 fewer than in past decades — while the number of children in care has risen in recent years to more than 8,800. That shortfall has left state workers desperate to place children, offering some foster parents up to $600 a night for little more than a warm bed.

Those sudden, heart-wrenching partings are a key reason foster parents say they leave the system. The state today has about 5,000 foster homes — nearly 1,000 fewer than in past decades — while the number of children in care has risen in recent years to more than 8,800. That shortfall has left state workers desperate to place children, offering some foster parents up to $600 a night for little more than a warm bed.

The state’s first step, foster parents say, should be to identify relatives faster. The state has a six-month backlog in its unit that searches for relatives, according to Kagi, who chairs the House Early Learning and Human Service Committee.

When the state does locate kin, Hanna says, “we have to start trying to get children to bond,” even if that’s through online chats. If relatives don’t demonstrate interest in getting to know the children, Hanna says, “after a certain point — which we haven’t defined — we want foster parents to be considered.”

Advocates for birth families agree that, especially given the digital tools now available to investigators, the state is inefficient at locating relatives of children removed from their parents.

“The department does a really crappy job of finding relatives,” said Shrounda Selivanoff, whose infant daughter spent two years in foster care a decade ago before returning home. Selivanoff now works for the Office of Public Defense to assist birth parents caught up in the child welfare system.

Selivanoff supported efforts to strengthen the search for relatives included in Kagi’s bill, HB 2761, that the lawmaker has now set aside. The measure would have required the Department of Children, Youth and Families to conduct an extensive family search as soon as the child is placed in state care and to report on its efforts at each stage in a child’s case.

But Selivanoff and other advocates for birth parents and relative caregivers objected to other provisions in the bill that, they said, would have put the interests of foster parents above their own.

The bill — which Kagi now says she won’t put to a vote this session — called upon judges to “weigh the benefits of relative placement with the stability provided by and attachment to a long-term caregiver” after a child has been in the state’s care for one year.

After deciding against a legislative fix this year, Kagi said that reforming practices under a new Department of Children, Youth and Families, which will be established July 1 and take over the state's early learning and child protection functions, will be more effective than changing existing laws.

“I completely agree with placing children with relatives as a first preference,” as required by state law, Kagi told InvestigateWest before her decision to drop the bill. “But when a child has been in a long-term placement and has created that attachment and bonding [to a foster family], I just think the court should be able to consider that.”

Birth parents and relative caregivers worry such changes would undermine their ability to regain custody. And children do best, they say, when they live with relatives who can keep them connected with their ancestry and culture. Maintaining that connection can be especially challenging for children of color, who are over-represented in the foster care system.

Foster families are overwhelmingly white, while more than 16 percent of foster children are classified black or "multiracial black," according to state data. With the exception of Native American children, the state may not make placement decisions based on a child’s race.

Selivanoff called it “dangerous” and “irresponsible” to give foster parents priority just because the state has failed to identify relatives quickly.

Such a policy “continues to fragment the black family,” she said. With the state struggling to recruit African-American foster parents, most black children will end up with white foster families. “And now you want [foster parents] to be the second consideration after birth parents,” Selivanoff said. “It’s outrageous.”

Relative caregivers are also “very sensitive to wording that would. . . put their interest behind a foster parent,” said Shelly Willis, executive director of Family Education and Support Services, which supports grandparents and other relative caregivers. More than four in 10 children removed by the state from their birth parents now live with other kin. Yet relative caregivers often struggle financially because they receive lower monthly reimbursements than licensed foster parents.

“We shouldn’t keep kids from family because the process [of finding relatives] is too slow,” Willis said.

Birth family representatives, foster parents and lawmakers vow to continue talking. All sides agree that the state’s child welfare system needs major revamping in order to rise from disarray and strain.

Many place their hope in the new Department of Children, Youth and Families.

“This is just the beginning of the conversation,” Frank Ordway, the state Department of Early Learning’s assistant director, told foster parents who had gathered around him at the Olympia rally to share their concerns. “There’s going to be a lot of opportunities to hold us accountable” in the new department, he said.