She explored extreme weather, health impacts and other fallouts of a warming world for vastly different audiences, but the exact same question was asked at the end of every talk: What can I do to be part of the solution?

“I never felt like I had a good answer,” Roop says. Emphasis on “had”: Over the past few years Roop — who now works for the University of Minnesota — collected her PNW-incubated experiences and shared them in her new book, The Climate Action Handbook, available mid-March.

Roop has long believed that every action, big or small — from advocating for clean energy to washing clothes in cold water to writing a song about climate change — can help avert the worst of the climate crisis. The book gives shape to the belief that so many actions can be climate actions, even if they don’t have a direct impact on someone’s carbon footprint.

Roop sat down with Crosscut to talk about what qualifies as a climate action and how we all can create climate habits. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

CROSSCUT: What are some of the biggest barriers you've seen to people taking climate action?

ROOP: I think one of the big ones has been that it is often framed around actions that require either high upfront financial costs or that are seemingly sacrificial, so they're not framed as being a benefit to you. Like, “You don't get to eat a hamburger anymore.” Right? That's actually not what the science says. The science says, “Let's eat less of those products. Not none of them.”

I think it’s useful to change the conversation from “What can I give up? Can I pat myself on the back because I've avoided this much CO2?” to instead saying, “How do I show up in the world? And what are the ways that I can help shape and create the future I want?” We should encourage people to evaluate the opportunity there is for supporting their interests.

CROSSCUT: How have you reframed something that felt sacrificial in your own life, in a way that made it feel like less of a loss and more of a way to sustain things you care about?

ROOP: I go through that process of justification and affirmation all the time. It’s a part of a journey where you’re being honest and reflective about why you’re doing something, what it’s amounting to, and being OK with the fact that you can do something for a lot of different reasons.

We don't really eat beef in our household anymore — there's just so many other great delicious things. I do eat beef but only from my friends’ farm on Lopez Island. And whenever I happen to go and buy some of their meat, then I have a really delicious hamburger. So it's about trying to reframe it: It’s not that I don’t get to eat it, but I created an experience around the thing that made it feel like a treat.

We're actually having to go through a very costly electrical system upgrade in our old house so that we can slowly integrate electrical appliances, like an induction range and a high-efficiency dryer. It's been very incremental because I don't have $15,000 burning a hole in my pocket.

The way that we've been actively reframing that — as I'm writing a check this morning to the electrician — is, it's good for our property values, for the planet, for our indoor air quality. There are all sorts of other things that this action and this expense are going to bring to my family and to my health and my well-being.

CROSSCUT: What have you learned about how people navigate both making changes in their own lives and not losing sight of the fact that systemic change ultimately really shifts the needle?

ROOP: I think that’s a tension that many of us in this space live with every day. And I think it’s not black and white, right? I am trying to remind people that individuals comprise the collective. So if we're trying to fill a bucket with solutions and actions, and everyone says, “Well, my drop doesn't matter,” then we're never going to fill the bucket.

And so I think we certainly have to have a thoughtful conversation about accountability, and who's accountable for having created the problem — I’ve tackled some of this in the book. This is where governments and, sadly, regulation and corporate accountability come into play.

When we talk about these big systems and levers, the people pulling those levers are individuals. People are designing the systems, and in the United States, in theory, it's people that determine what the collective response is [from voting with your dollars to calling your representatives]. And we do that through being civically engaged citizens.

One of the things that was very eye-opening for me in writing this book was, there are over 500,000 elected officials in this country, but we often only think about a handful. Really, we could be looking at our very neighborhood: Who might be the city councilperson who is deciding whether there's a climate action plan that gets put in place, or whether our water-supply systems are being designed with climate in mind? And that is where a conversation with your neighbor about that could become a collective action.

CROSSCUT: Has what you’ve learned writing this book influenced changes in your own approach to climate action?

ROOP: I really mean it when I say this book was a way to inform my own journey, because I just had no good answers. My answers were: Buy an electric vehicle; if you can, put solar panels on your roof, do; have a climate conversation. Those are all important things, but they just are not enough to really keep us on this journey long enough, right?

It has created some marital discord. I will be very honest. My husband loves to idle the car. And now that I know how terrible that is, not only for the climate, but also for my wallet, it’s a source of tension. My blood boils every time I see it happen.

I’m not perfect. I don't want anyone to think I'm just out there, a Climate Warrior, I’ve already done all 100 things in this book. No. I'm a human.

Crosscut: You’ve mentioned how important it is to have a climate community. How do you go about making a community that's climate-focused?

ROOP: I think you de-emphasize climate being the primary driver. Your climate community is probably the community you're already in, whether that's a faith community, your weekly book club, your school group, your board-games group. The reason is, it's something you care about, you can open up the conversation and the opportunity for action, to show how climate change will alter that community you are in or is a value you share. That is where we have, I think, the greatest opportunity for influence, but also that greater opportunity for sustenance.

That's not to say there shouldn't be dedicated groups convening around climate. But I invite people to think more broadly about what it means to be in community, and having climate be part of it.

And the science is very clear: People who have strong social and community ties weather the storm quite literally far better than those who don't. Just being invested in your community can bring climate benefits to you and your community.

CROSSCUT: You stress that environmental justice is an important issue and some people individually could have substantial climate impact by changing their lifestyles — like people who fly the most. How do you write a guide for everyone, while also emphasizing that some individual actions or some people's actions, not only matter a lot, but need to happen?

ROOP: I don't discount that reality that some of us, myself included, should be doing more and should be doing every action in this book, and using the influence and the connections we have in our communities. But I feel like also, everyone should be using their strengths, their passions, their connections to community and the things that they care about, right? Everyone's an expert in the future they want to create, and climate is unquestionably part of our future. So then it becomes up to us as our own individual experts from our own walks of life, to see where climate change will alter something we care about, and then find some way to help you create that vision.

CROSSCUT: What are some of the most important mitigation and adaptation measures individuals could be taking in the Pacific Northwest, compared to somewhere like the Midwest?

ROOP: This is an interesting question, where the nuances of each action come into play.

If you plug in an electric vehicle in Florida, where most of the power is coming from coal, it's not as impactful as an electric vehicle that's being charged by hydropower in Washington state. And there are different trade-offs associated with those different energy systems. Understanding your own context, and what works and what has value and impact in it, was part of the intention of the book.

But should you still have an electric vehicle in Florida? Yes, if a life-cycle analysis still supports you.

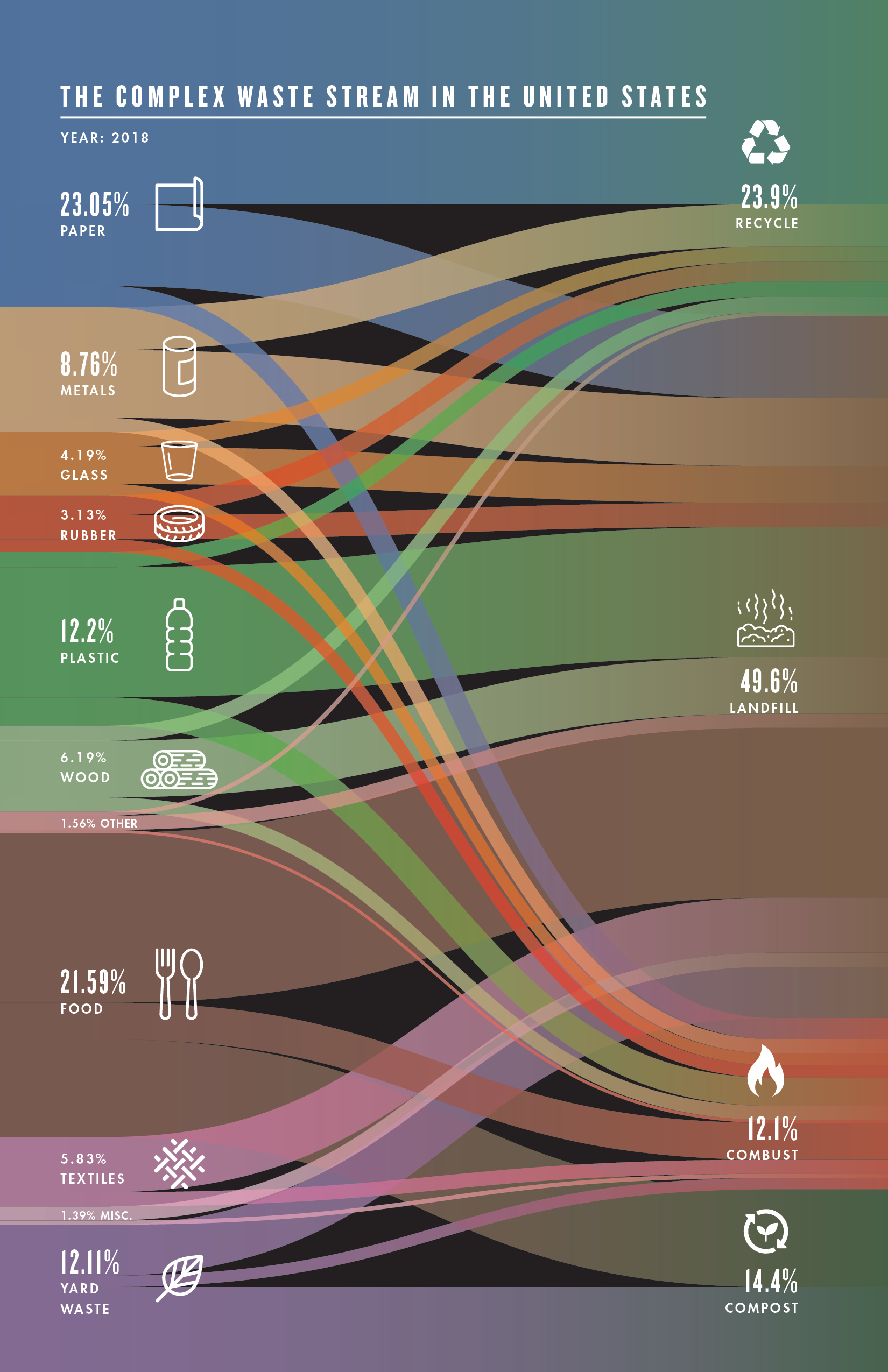

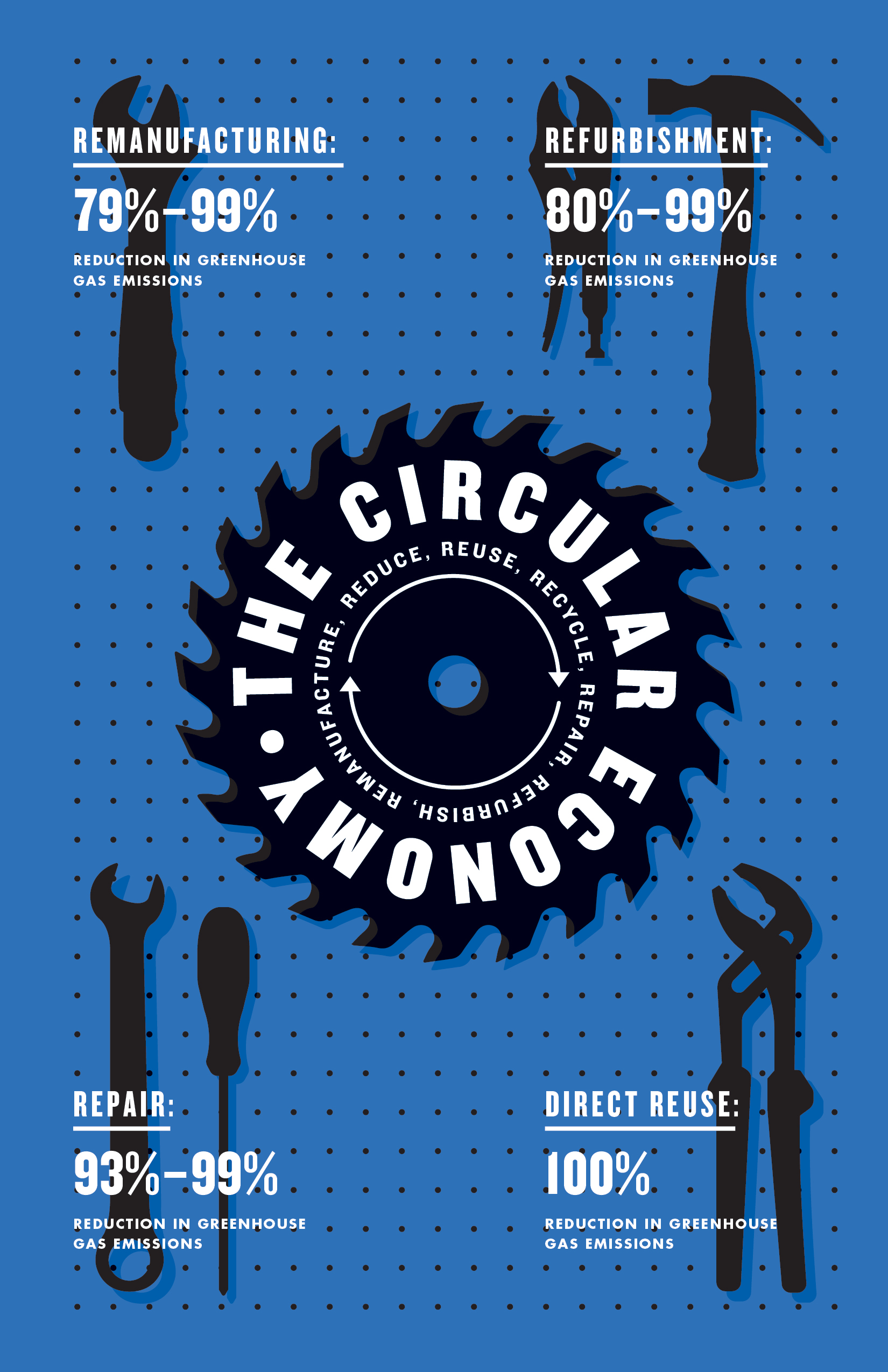

Every place needs more individual and systems-level resilience and preparedness. And dietary change, how we handle our waste, food waste and composting, are things every place needs more of.

CROSSCUT: In your book, you talk a lot about the hazard of focusing too much on impact — especially on carbon footprints — and trying to figure out which climate actions are quote-unquote “best.” What do we risk when we focus too much on what’s quantifiable?

ROOP: I intentionally avoided putting numbers on things because what we all value and how we contribute can take such a multitude of forms.

The conversation has often focused on emissions reductions. That can be really alienating for a lot of people, because the way you quote-unquote “make a big impact,” with the biggest number associated with it, is buying an electric vehicle, putting solar panels on your house, weatherizing your house. And those are important things, and they do move the dial insofar as they have a big return on carbon investment. Counting is helpful, because it can help you feel cognitively like you're making progress.

But the other side of the solutions coin is, preparing for the changes we know we've set in motion. There are things about the climate system that we have altered, and we have altered in a very meaningful way, for a very long period of time. If you want to bring this home to Washington state, think sea-level rise. That change is something that people are grappling with: How do we accommodate that?

So as we think about the solutions landscape, I really wanted to showcase opportunities where people were thinking more about resilience and preparedness, those being, I think, quite frankly, ways for more people to see themselves in solutions. They don't require $80,000 just to get in the door, to feel like you're having a big impact. But being an artist and being creative, and communicating, that could be the catalyst for change. So I was really trying to reframe, what is valued? And who has value?