“Why people are so troubled by this decision is that it's just looming like a specter out there,” said Dennis McLerran, environmental attorney for Cascadia Law Group and former EPA regional administrator for Washington, Oregon, Idaho and Alaska under former president Barack Obama. “We don't know what it will mean eventually.”

The ruling was related to the Clean Power Plan, an Obama-era regulation under the Clean Air Act that set carbon-dioxide emission guidelines for power plants. It was blocked by the Supreme Court in 2016 and never went into effect. The Supreme Court’s June ruling West Virginia v. EPA, stated that Congress did not give the EPA the specific authority to adopt this type of regulation. Although the EPA still has the authority to regulate power plant emissions within each facility’s boundaries and the agency is expected to pursue additional regulations in the future, McLerran said, much of the enforcement comes at the state level.

Washington has one of the cleanest power grids in the country, with hydroelectric power making up about two-thirds of its electricity generation from utility-scale and small-scale facilities in 2020 and wind power accounting for about 8%, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. But it also relies on such resources as natural gas and coal, some of which is imported from out of state and Canada.

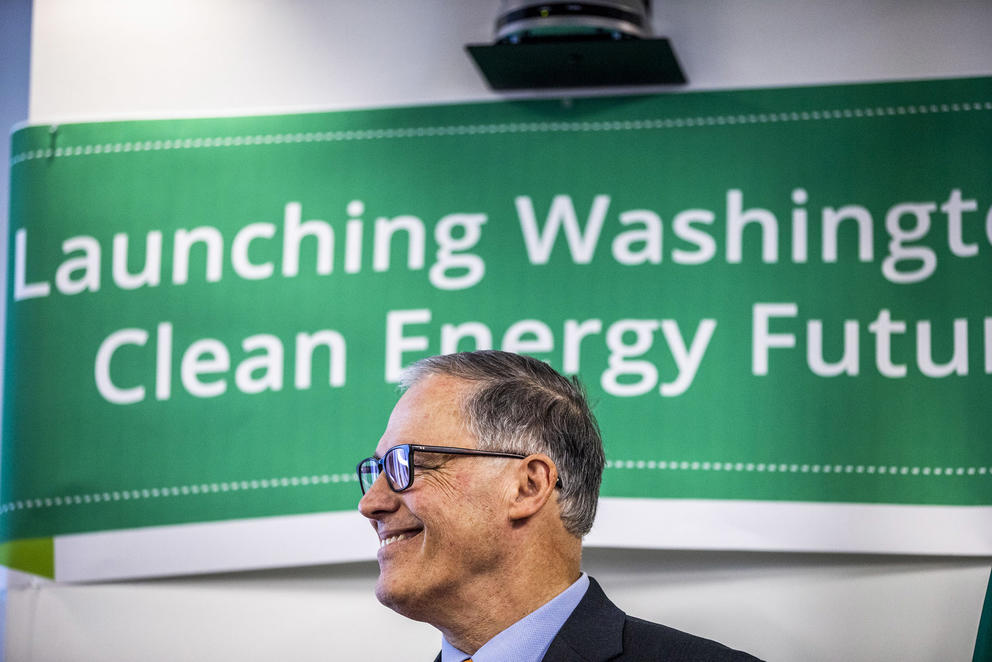

In 2019, Gov. Jay Inslee signed the Clean Energy Transformation Act, which requires utilities to be greenhouse-gas emissions-neutral by 2030 and produce 100% clean electricity by 2045. The state’s only coal-fired power plant, TransAlta in Centralia, has shuttered one of its two boilers and is expected to stop burning coal altogether by 2025, following a 2011 legislative decision.

But that doesn’t mean Washington will be completely untouched by the Supreme Court’s decision.

McLerran explained that this decision could impact federal agencies’ rulemaking abilities under such statutes as the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act. There is now the chance the court could respond by saying, “They didn't have authority to do that, they needed more direct congressional authorization,” he said.

There have been many instances in which leadership in Washington implemented rules building on environmental federal statutes, he explained. And without the federal statutes, the state’s own policies could come under threat.

It is also important to remember that Washington does not function in a bubble, and will be impacted by environmental regulations far beyond its borders.

“If the nation does not have laws that drive down emissions, then Washingtonians still experience the impacts of climate change,” said McLerran. “The higher temperatures in streams, the loss of snowpack, the loss of glaciers, impacts to salmon — all of those things that flow from climate change, if the country is not able to address those, Washingtonians are impacted.”

Following the Supreme Court’s recent decision, Inslee said it was as though the justices took a “wrecking ball” to the EPA’s ability to curb pollution, and that it emphasized just how important state-level restrictions have become.

Miles Keogh, executive director of the National Association of Clean Air Agencies, compared the situation to a boat that must continue steering with some of its oars removed. Now, he said, states like Washington that are taking the climate crisis seriously have to row even harder.

They must take key steps like cultivating their electric-vehicle industries and dramatically decreasing greenhouse-gas emissions from factories and power plants, Keogh said.

But Washington state Sen. John Braun, R-Centralia, said in a statement soon after the decision that this simply comes down to the rule of law and putting power back into the hands of elected officials.

“It is up to Congress to authorize new regulations that the EPA has been implementing on its own, especially regulations that carry billions of dollars in economic ramifications,” he said. “Executive-branch officials don’t get to do this themselves.”

In January the state is set to implement its Climate Commitment Act, a cap-and-invest program that is expected to involve increasingly stringent limits on greenhouse-gas emissions for the largest polluters along with a system of allowances. That month also marks the start of the Clean Fuel Standard law, which, similarly, requires fuel suppliers to reduce the carbon intensity of their fuels. By 2038, they are expected to be 20% below 2017 levels.

Washington is also working to follow California’s lead and require all new cars and trucks sold in the state be zero-emission by 2035.

State Rep. Joe Fitzgibbon, a Democrat who sponsored the clean fuel standard legislation, said state policies have already surpassed those that would have been implemented under the national Clean Power Plan. Now is the time to focus on “[implementing] them successfully and show other states that you can decarbonize your economy and still have a really healthy economy and be a great state to live in,” he said.

Joel Creswell, climate policy section manager at the Washington Department of Ecology, said the state has become a leader in these types of environmental policies and a model for states looking to craft similar legislation.

“There is very much this sort of mentorship ethic and dynamic of sharing information and expertise across the states because ultimately we're not in competition,” he said. “We all need to get our emissions down to zero and so the more we can help other states do that, the better off we'll all be because the climate is something we share.”