The world’s largest hornet, Asian giant hornets earned their nickname — “murder hornets” — mostly because of their penchant for chewing the heads off of live honeybees, a favorite snack. Asian honeybees that evolved alongside these insects have developed some interesting defenses against them, but the European honeybees that live in North America are sitting ducks. And it's likely they aren’t the only species that hornets want on the menu.

Honeybees, of course, make gardens grow near Adira’s home in Tacoma. Without them, she says, “vegetables won’t grow … and we won’t have honey, and our flowers won’t get pollinated.”

Adira and her mother Bevin Hall caught the figurative hornet bug after watching state Department of Agriculture videos showing last year’s successful removal of a giant hornet nest in Whatcom County, the only nest found to date in Washington. The hornets were scary, and the videos drove home how important it is to prevent the species from establishing itself in the state.

“It feels like we have such a window right now to be able to control the situation,” Bevin says.

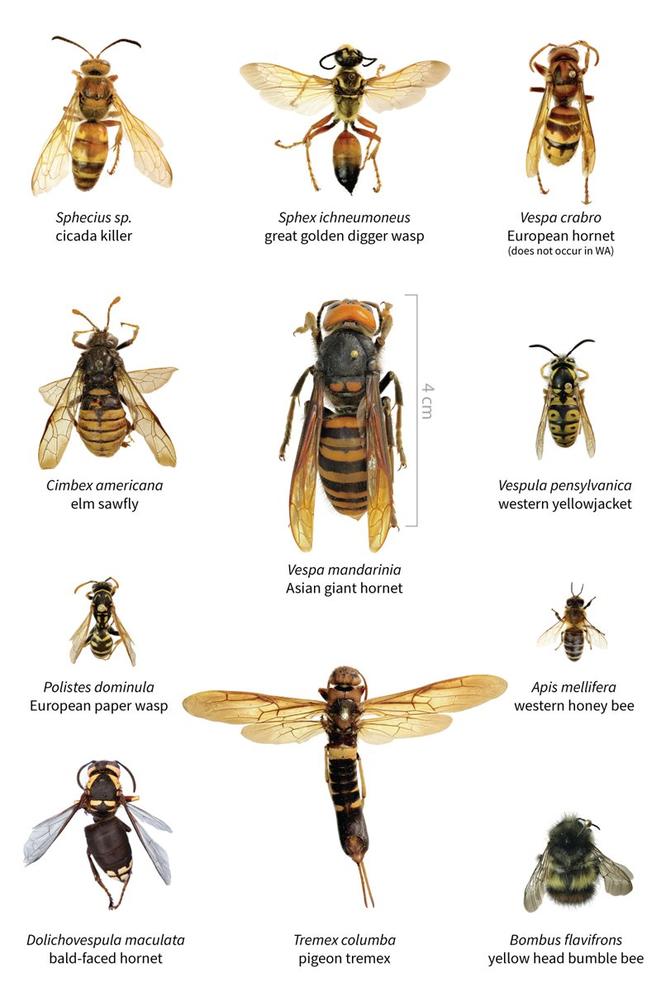

The Halls are among thousands of residents concerned enough about the hornet threat to join the state’s 22-week community giant hornet trapping program. Beyond the trappers, many others are paying attention: beekeepers, entomologists, farmers and everyday Washingtonians for whom the term “murder hornet” hasn’t sat well since the 2-plus-inch wasps were the subject of a New York Times article in May 2020. Building a trap, and following what’s happening on a state Department of Agriculture community Facebook page, are ways they can turn that concern into action.

“It’s so easy to build a trap and log our findings and be a part of it,” Bevin says.

But two weeks into the second summer of hornet trapping there’s been relatively little activity in the hornet world. Ears perked up in June when a very dry, very dead hornet was reported in Snohomish County. But it had probably been there since last year, and didn’t raise alarms about hornets spreading anew undetected. State officials are encouraging citizen scientists to set up traps in Whatcom, Skagit, San Juan, Island, Jefferson and Clallam counties, and, more recently, in Snohomish and King counties.

“Going into this season I still feel pretty positive about our ability to contain and eradicate the Asian giant hornets. But it's a difficult one to track. And so it'll take a number of years to really understand what its current distribution looks like,” says Todd Murray, a pest management expert at Washington State University who has been a point of contact for Asian giant hornet community engagement. “We're at a very early stage of the invasion curve of the species, and that is the one time in that part of the invasion that we have a shot at actually controlling [things].”

State and community trappers are waiting with bated breath and baited traps. For now, there’s a tentative optimism about Washington’s chances and time to really review what’s been learned so far.

“We still have a lot to learn,” says Karla Salp, a public engagement specialist with the state Department of Agriculture. “The reality is we only have one season’s worth of data. … There’s still a lot of unknowns.”

Combing through the knowledge

Thanks to research and debriefs done over the past year — hugely supplemented by community observations and trap contents — entomologists in the state and the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service have learned a lot about giant hornets and how best to deal with them.

The most important lesson was that Washingtonians not only could but would contribute in a significant way to monitoring. In other places where pest managers have tried to get residents to monitor and trap invasive bugs, Salp says, they’re lucky to get 50 people. Washingtonians set up 1,500 traps last summer, with at least 505 traps set up this summer as of July 15.

“I can't think of another time where we've had anywhere near this level of community support,” Salp says, noting that people invest their own time and money into this project.

Hornet traps are simple devices, with community members and state trappers using the same materials: two-liter plastic jugs, hung from trees and filled with everyday cooking supplies like orange juice and rice cooking wine. Trappers cut star-shaped patterns into the jugs, which they fill with sweet, stinky liquid. Hornets attracted to the bait crawl their way into the entry and drown in mixture. The state also sets out live traps, which include a screen above the bait to prevent the hornets from drowning.

Judy Cobb Dailey, a community trapper living in Seattle’s Montlake neighborhood, said her husband “moved heaven and earth” to install their first beehive within neighborhood regulations in June. She didn’t expect building a hornet trap would cost $70, a fair amount for a science project.

“My grandson immediately drank a couple of juice boxes and my daughter needed rice cooking wine, and I will have to replenish our supplies,” Dailey says. But the trap installation instructions, she says, were excellent. “We feel we are protecting our neighborhood. And I hope to God we don’t get a hornet.”.

Last year, about half of the 31 confirmed sightings of hornets in Washington state came from community members; across the border in British Columbia, all six confirmed sightings came from community members.

Kim Baxter of Oak Harbor got involved in trapping last year after feeling convinced that she had seen an Asian giant hornet in real life. “The head ... and the size were so distinctive [that] when I saw the picture of it, I was like, that was it,” Baxter says.

Setting up the trap — which she points out to friends when they visit — was easy, Baxter says. And while the trap doesn’t add much aesthetically to the aspiring master gardener’s wooded 5 acre lot, it could serve the pollinators that traverse Baxter’s lavender, clover and squash; her husband has intentions of keeping bees.

Baxter says she knows state employees need the amateur hornet catchers like her to keep a lookout. “It’d be impossible to cover as much ground without having more eyes out. You just can’t monitor the whole state.”

State scientists are still going through last year’s traps. “The response from the public was so much larger than we had anticipated, which is part of the reason that they’re still going through insects,” Salp says. As a result of community trapping last year, investigators even discovered that there are Leptopilina japonica — a problematic wasp — in the state, something no one had detected before.

People also worked out the kinks of trapping in important ways last summer. Salp says scientists realized hornets could escape from the initial live traps because of their square entryway design. To prevent escape, the state changed their traps midseason, and adjusted the design recommendations given citizen scientists: The advice now is to cut an asterisk into the sides of the jugs. This summer, the state is also advising people to bait traps with a brown sugar mixture that has worked well in trapping European hornets on the East Coast.

“We learned a lot last year,” says Anne LeBrun, national policy manager with USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service.

Scientists like Murray’s WSU colleague, David Crowder, started projects using last year’s community data. Based in part on those submissions, Crowder has been developing digital tools to help inform the state’s trapping efforts, relying also on climate and wind patterns that may promote the spread of the hornet.

The USDA is also coordinating two research projects to better understand the giant hornets and improve the eradication program, LeBrun says. These projects include a multiyear molecular research project looking at the genetic diversity of the hornet in its native range in East Asia, particularly Japan, to figure out where North American specimens originated from and whether it could establish here. Also under development are tests that can identify whether Asian giant hornets are responsible for dead beehives. DNA found in fecal pellets in the extracted nest is being sequenced to identify what Asian giant hornets’ are eating in Washington.

Another project aims to improve lures used to capture hornets, the first step in following live hornets back to their nests. The USDA’s Agricultural Research Service in Wapato is identifying pheromones and food attractants specific to the life stage of adult hornets.

What the actual threat is

That the hornets are quiet right now doesn’t mean there isn’t a lot to do.

The state aims to set 1,100 traps this summer, with at least 655 up so far. Salp says no giant hornets have been reported yet.

WSU’s Crowder co-wrote a paper showing that Washington state is the type of place where giant hornets can establish themselves. Giant hornets prefer wooded areas, of which Washington has plenty. But climate change may throw in a wrench to where the hornet expands.

“With all invasive species, ecological disturbances are kind of what their jam is,” Murray says. Those disturbances — drought, exposed soil, fire and beyond — may create conditions conducive for invasive species, Murray says. “For [Asiant giant hornets], it’s hard to say whether the Pacific Northwest climate model predictors will help or deter it.”

But despite the unknowns, there are no indications that Asian giant hornets are a big concern of pest managers or beekeepers right now.

Japanese beetles are plaguing Yakima, Murray says, while European chafers tear through lawns in Puget Sound and Asian long-horned beetles continue to cause hundreds of millions of dollars in damage to North American cities. “There are definitely very highly concerning pest threats out there right now,” he says.

Kevin Oldenburg, a beekeeping hobbyist and president of the Washington State Beekeepers Association, says his thousands of members are aware of the giant hornets but are more immediately concerned about other threats, particularly the varroa mite — a parasite that sucks fat off of live bees and transmits viruses — and bee-killing pesticides.

“If you ask a beekeeper, ‘Name your top five concerns about beekeeping,’ they're gonna say varroa mite, varroa mite, varroa mite, pesticides, pesticides,” Oldenburg says.

Few Washington beekeepers have even seen a giant hornet. So far, Oldenburg hasn’t heard of any of his beekeepers losing a hive or seeing one attacked yet this year. “I think everybody on the west side is really very watchful of it, but I don't think it's a real big concern,” he says.

Baxter, the Oak Harbor-area hornet trapper, has mentally prepared for what she’d do if she saw a bee-killing hornet. She carries her cellphone in the yard more than she ever did, just in case she needs to take a photo before it flies away. “I’ve thought about different ways,’ she says. “If I see one, could I trap it under a bucket or something? But I think I’d be able to react and contact people.”

Silver lining: community engagement

Regardless of whether they find hornets, Washingtonians participating in trapping have given themselves learning opportunities and have connected with nature.

Bevin Hall and Adira Meiches set up their trap — a repurposed cranberry juice bottle filled with rice cooking wine and orange juice — in a palm tree in their backyard. Once a week, they dump out the trap, and identify the insects they catch; so far, Adira says, they’ve found only ants.

The first week at Dailey's trap in Montlake yielded an “amazing” number of fruit flies, as well as two flies and 17 bees. “Queen bees lay 1,500 to 2,500 eggs a day, so we aren't too worried about killing 17 bees per week,” Dailey says. “The process has been fun and easy. My grandson and I are learning more about insects.”

Even in their fairly urban Tacoma neighborhood, Bevin Hall says, trapping provides a way for people of all ages to get to know the natural environment without having to put in too much work.

“There’s so many things we didn’t know were in our environment that matter,” Bevin says, “All the bees and wasps and hornets matter.”

“And the butterflies and moths,” Adira adds. “Everything matters.”

Update: On Wednesday, July 21 at 2:01 p.m., this article was updated to reflect that the state detected Leptopilina japonica, not spotted wing drosophila, for the first time thanks to Washington resident trappers. Leptopilina japonica attack spotted wing drosophila.