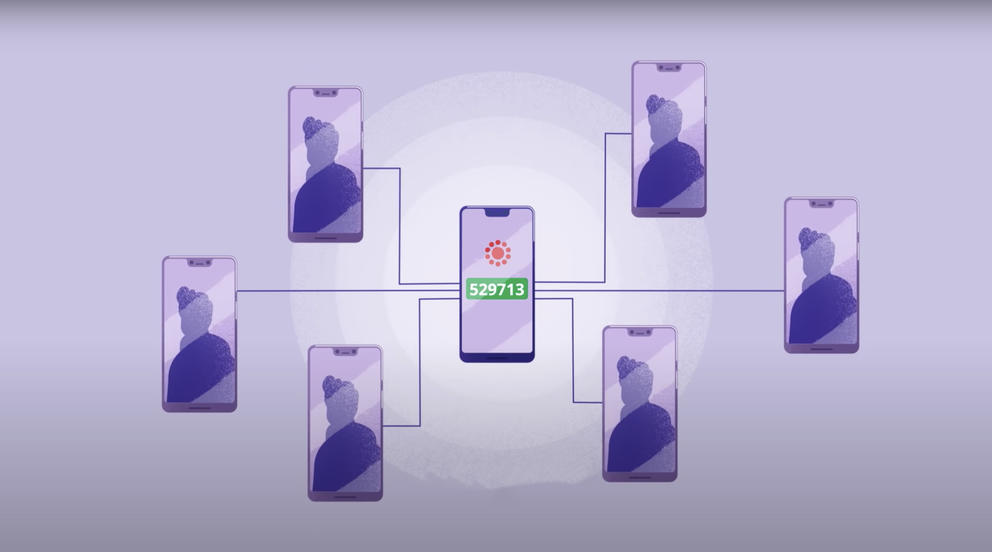

If a person confirms they have COVID-19, the app sends an anonymous exposure notification to other users of the app that the diagnosed person may have interacted within the previous two weeks. Users of the app won't be able to tell who was notified or whom they were notified from. (Washington Dept. of Health)

“The impacts of this pandemic are very real, and I believe this app will save lives,” says Bell, a marketing and public relations consultant who helped launch Black and Healthy Pierce County, a COVID-19 information outreach project.

With infections surging, on Monday, Washington joined more than a dozen states to offer free, opt-in smartphone technology in hopes of making a dent in hospitalizations and deaths.

The technology is thought to be effective even at low levels of adoption. By Wednesday afternoon, more than 875,000 Washingtonians (about 11% of the state’s population) elected to participate, says John Wiesman, the state’s secretary of health.

Built on technology co-developed by Apple and Google, the WA Notify app uses Bluetooth functionality in smartphones to work as a coronavirus exposure notification system. Android owners can download it from their app store, while iPhone users can toggle on the service in their settings menus. When smartphone owners who’ve opted in are out in the world and near each other, their phones anonymously trade encrypted, untraceable and randomized numbers that serve as logs of possible contacts. If one of them tests positive, that person can upload a PIN code to the app. Then, the app notifies anyone who has downloaded the app and spent more than 15 minutes within 6 feet of the infected person over a 24-hour period. The notification does not identify the source of exposure.

While not a replacement for case investigation or contact tracing, the application may offer advanced warning for those efforts, especially for strangers near infected people.

Before approving the app, the state worked with the University of Washington on app design. The UW conducted a 2,800-person survey of Washingtonians’ thoughts and concerns about the technology and started a pilot test Nov. 2 with the university community involving 3,500 participants. The state also waited for a recommendation from an exposure notification technology oversight committee with at least 18 members.

“Given the importance of privacy, Washington felt it was important to carefully evaluate this technology before launching it statewide,” says Amy Reynolds, communications director of the Department of Health. “Once we received a recommendation from the state’s oversight committee to adopt the technology, we moved quickly to pilot phase with the UW.”

Rollout

Reynolds says Washington does not have an adoption goal, but that the greater the number of people who use the app, the more effective it will be. Rapidly approaching a million downloads in its first week alone, the app and Washington have entered a sort of honeymoon phase of adoption.

“One reason I'm grateful to have it is that I have a friend [who has the app] who is having a really hard time with the isolation and loneliness,” says Jan McClurg, a Washington resident. “She continues to travel as much as she possibly can, so I'm glad I will know if she's been exposed on one of her excursions/flights. More reason than ever not to get near her!”

Amy Zhang, a Seattle-area resident physician, downloaded it because she wanted better information about her exposure levels outside hospitals. “I’m not aware of being exposed to any COVID-19-positive individuals in public, which is part of the problem, and why I’m enabling this. In terms of health care-related exposures, I don’t think this will be that helpful because usually those patients aren’t in a state where they have their cellphones on them, and we don’t already have whatever COVID-19 test results are available for them,” she says.

Still, misinformation about the app’s functions, security features, access to personal information and even impact on the phone’s battery life can hinder adoption. Plenty of Twitter and Reddit threads are devoted to users trying to educate each other.

“Since WA Notify uses Bluetooth Low Energy,or BLE, technology, the energy consumption should not be too impactful on day-to-day use of someone’s phone,” says Dr. Janet Baseman, an epidemiology professor at the UW. “The biggest challenge I’m thinking about is being able to explain the system well enough so that people will understand how it works and that their personally identifiable information is not being shared with anyone.”

Is it working?

The Department of Health’s Reynolds says the department does not have access to information about how many exposure notifications have gone out since the app launched Monday. “Our understanding is that high-level aggregate data is a future Apple/Google improvement,” she said via email Wednesday evening. “People would have to opt in or opt out of the aggregate data collection.... We do not know which aggregate data elements [Apple or Google] intend to capture, but do know none would be linked to individuals or contain personal information, which isn’t collected.”

The kicker of the program is this: Exposure notification systems work only when lots of people sign up for them. If you don’t use the app, you can’t get notified.

“It can only work if people sign up and then respond to alerts by testing and staying away from others by self-quarantining,” says Dr. Matthew Golden, medical director of Public Health — Seattle & King County’s COVID-19 contact tracing program. “Signing up is something we can all do to protect the people we care about and our community.”

One problem is persuading people to sign up for a program before it’s useful. “Our main barrier to make the systems effective … is gaining widespread adoption,” UW computer scientist Dr. Stefano Tessaro noted during an Oct. 21 talk. “Accuracy of the system ends up increasing trust, but it is trust that increases adoptions, which in turn increases accuracy.”

That weighs on Christian Bell. While the app gives her a new sense of safety, she worries that not enough people will download the app. Still, she feels it’s worth downloading as a part of our pandemic toolkit. “Though no one intends to put others at risk, it can happen. Just like wearing a mask or social distancing, we need to utilize this tool to help stop the spread of COVID-19.”

The linchPIN

Another hurdle: Once someone using WA Notify tests positive and receives a PIN code, the burden is then completely on that person to input that PIN, so all their potential contacts can be notified. Whether that second layer of adoption occurs remains to be seen.

Public Health’s Sharon Bogan said Wednesday that the county health department had just given out its first PIN and was working on issuing a second. “Since this is just starting, it’s too early to tell how the process is going and any potential impacts on COVID-19 in the community,” she says.

That unexpected hurdle has damaged efforts in states like Virginia, which started its Covidwise notification system Aug. 5.

“It's completely up to [app users] as to whether they put it into the system or not,” says Jeff Stover, director of health informatics and integrated surveillance systems at the Virginia Department of Health. He says about 65% of the PINs given out have been validated within the three-day validity period. “You’d like that to be higher,” Stover says, suggesting a 95% validation rate as preferable. “I think we would all think that if you'd already downloaded it, then you’re already sold on doing this, but not necessarily so. So I think that’s definitely something that is a hiccup and potentially a challenge.”

In past weeks, Gov. Jay Inslee and other officials have touted the value of these apps by referencing a joint Google Research and Oxford University preprint suggesting that Washington could reduce infections by about 8% and deaths by 6% with only a 15% adoption rate. However, the researchers behind the preprint study — which focused on King, Snohomish and Pierce counties in Washington state, and has not been peer-reviewed — recently noted they did not factor in whether those infected might elect not to upload the codes needed to make the system work.

“I can’t be too concerned about relying on users to take this action because there is no alternative…. It is how the system is designed,” says UW epidemiologist Baseman. “I think the responsibility that we have is to do the best job we can explaining how WA Notify works so that people are willing to enter in their codes because they understand that it is how our communities get a benefit from the program. I enter my verification code to provide benefit to you, and you enter your verification code to provide a benefit to me.”

Sometimes, people who want to enter PINs can’t. Margaret Turlington, a resident of Arlington, Virginia, who tested positive with a home test, documented in a Twitter thread the difficulty she had initially in making Covidwise work as intended because she couldn’t get someone on the phone to give her a PIN code. “I am a very educated person, a person who has been diligent about COVID, who is trying to do the right thing, and I ... can’t? No wonder infections are spreading unchecked when someone who cares can’t report! Imagine if I cared less!” she wrote. She finally managed to upload her PIN about 48 hours after her diagnosis.

Others might avoid uploading their PINs out of a sense of shame, even though the notifications are anonymized. Turlington says she definitely felt that shame, and shock, given how hard she’d worked to stay safe. “I [felt] like I should have done something that I didn’t, but I think right now, the most important thing is not to shame people and share stories, so people have the chance to learn and make better choices for themselves,” she said in a direct message. “[These] apps are great because they deal with some of the shame feelings because no one has to know who you are.”

The Virginia Department of Health’s Stover says the introduction of a national key server might make it easier to give people PINs through text. “If we can make getting PINs to people easier, then we're making the whole process easier. And hopefully more people are actually putting them into these apps.”

Reynolds says her agency, the state Department of Health, does not have access to information regarding the proportion of PIN codes uploaded to the app relative to the total number generated.

When asked Wednesday what the state is doing to explore how it can bolster the rate at which people actually follow through with uploading a PIN, Wiesman was sober. “The really important piece here is that when somebody tests positive and public health workers reach out to them, number one, we need people to answer the phone call back,” says Wiesman. WA Notify PINs are given out by public health employees over the phone, making that phone interaction — where they can answer questions about the app and speak to any lingering concerns — crucial.

“I think time and rapport with the case and contact investigator, that is an important piece, as well as just the marketing about WA Notify and that as people sign up they basically know how it works,” he says.

Baseman says the UW is working with the Department of Health “to answer key questions about the program and how to improve it in the coming months.”

Future expectations

A couple months in, Stover says the value of the app has been giving more people In Virginia an opportunity to appreciate their exposure risk.

“If we have a tool that can help us to at least increase the likelihood that I [know I] may have been exposed to someone, even if I may be asymptomatic right now, I think that the largest value is in knowing that I potentially need to alter my behavior,” Stover says. “It really puts you in somewhat of the driver's seat of knowing what's going on in your own personal world, and how you're potentially impacting others.”

Even people who aren’t sure the app will help, still think it’s important to download. Zhang, the Seattle-area resident physician, says that even without testing, most nonessential workers can make better decisions with this information in hand, such as whether they should quarantine or work from home. “Currently, we're not doing enough to try to reduce COVID-19 transmission, so more is always better,” she says, noting recent studies showing the inadequacy of symptom screening and temperature checks.

Graham resident Jessica Houston says the app is still worth it to her, even if all it does is keep safety on people’s minds. “I’m not sure it will do anything ... [but] the fact that it might help is huge,” she says, “even if it’s only a reminder to continue being very, very cautious.”