After appearing to be dead for the past three years, Seattle’s biggest arts and music festival has sprung back to life with new presenters, new energy, more affordable ticket prices and a civic hope that this isn’t just a brief resurrection, but the start of renewed life with many years ahead.

Here’s the shorthand: This year, Bumbershoot runs just two days (Sept. 2-3); it’s cheaper than in recent years at $75 for a single day, $130 for a two-day pass (early bird tickets sold out fast at $50 for one day and $85 for two); there’s a ton more visual and performance art than seen in the past decade; and the music lineup includes Fatboy Slim, Brittany Howard (of Alabama Shakes), Sleater-Kinney, Band of Horses, AFI, the Descendants, Valerie June and some 60 other notable bands.

Billed as the 50th anniversary, Bumbershoot is being staged by newly created nonprofit Third Stone along with producer team New Rising Sun. (Both organizations are named after Jimi Hendrix songs, which in Seattle is a good omen.)

New Rising Sun is a trio of seasoned Seattle event pros, including Joe Paganelli, general manager of McCaw Hall. Steven Severin, a concert booking vet who has run Neumos for the past 20 years, is overseeing the fiercely debated Bumbershoot music lineup.

Greg Lundgren, known for curating “Out of Sight” exhibits during Seattle Art Fair and founding the Museum of Museums, is helming the extensive visual arts effort with a team of co-curators who have programmed films, installations and happenings.

There will be working artists scattered all over the grounds, and the sketches I’ve seen make the setting look a bit like “Pee Wee’s Playhouse” in real life. Kids under 10 get in free, with the intent of making it a family-friendly festival again, not just catered toward the teenagers that have dominated the last few fests.

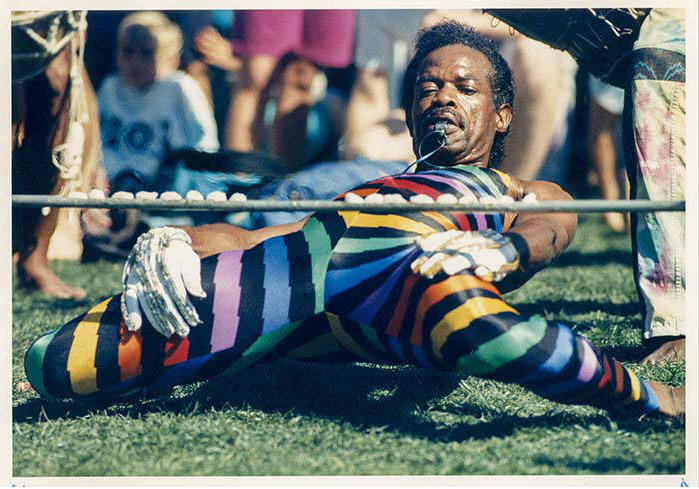

The organizers also have a whole bunch of oddities planned that you would never find at a standard music festival, which might be the most interesting aspect of Bumbershoot this year. A brief selection from the website lists witches, wrestling, nail art, sign spinners, robots, a tattoo runway, extreme pogo sticking and more.

There’s also a “cat circus,” whatever that is. (Of any single element, this seems to be what many of my friends are most excited about.)

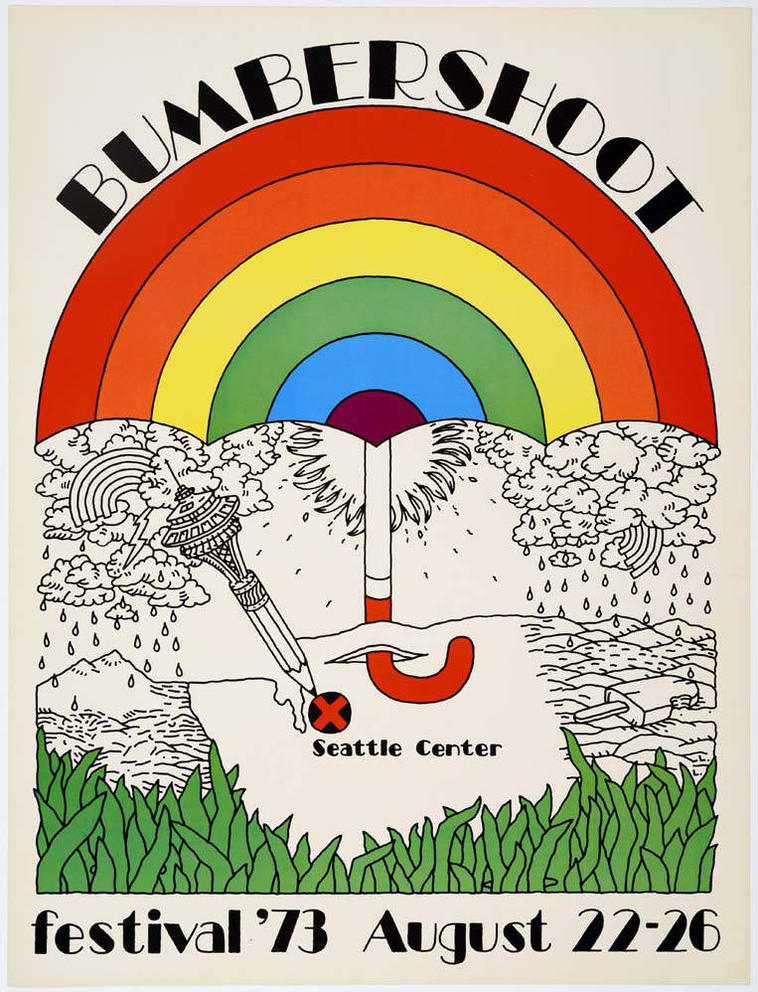

In fact it sounds a lot like the original Bumbershoot, which started on a shoestring budget in 1971. That first year was a much funkier affair called the “Mayor’s Arts Festival,” which was an outgrowth of hippie festivals that had popped up across the country in that era.

The initial event included light shows, art cars, fencing and logging demos, puppeteers, indoor motorcycle racing, Smokey the Bear, a 20-foot-long functional guitar, plus dance, literary events and a slate of local bands playing live music.

At some point during the ensuing years Rolling Stone called Bumbershoot “the mother of all festivals,” in part because few attempts anywhere were so all-encompassing. Though music was what drew most people in, for decades the varied selection of arts and just plain weirdness was the hallmark of Bumbershoot — and what kept attendees loyal.

“In 2009, I saw Pacific Northwest Ballet perform The Goldberg Variations within the Bumbershoot grid,” frequent festival attendee Sandra Keller recently recalled. “[I] couldn’t get over how fortunate it was that Bumbershoot included authors, comedy and arts other than music because their performance was mind-bogglingly brilliant.”

You never knew what you might discover at Bumbershoots of yore, and this year’s event is aiming for some of that weird serendipity again.

But for all the creative programming, questions remain about the future of the festival.

After a three-year pandemic break, will the throngs return to Seattle Center? Will this year mark the rebirth of a healthy Bumbershoot baby, or the last gasp of an event that has been incredibly difficult to execute all these years, with financial losses almost every year? And just what might happen at that cat circus?

These are the kind of imponderables that keep Severin awake at night. A couple weeks before the festival he sat down with me to explain why he jumped into the fray, and what he wants this festival to become.

Severin has been one of Seattle’s most successful concert promoters and he’s old-school, having started at much-loved club RKCNDY in the late 1990s. But he’s never tackled anything quite as complex as Bumbershoot — few in the industry have. He says it takes a certain kind of “crazy passion” to attempt to resurrect Seattle’s most-beloved festival.

“It really started during the pandemic when I thought we were going to lose Neumos, because I thought we were going to lose all music venues,” Severin said. “I got to the point that I started fighting for other people around the country, and that gave me a renewed energy.”

Severin was instrumental in national and regional efforts to save music venues during the pandemic closures, and those efforts worked: The local organization Keep Music Live WA raised millions of dollars, which with other grants kept venues alive even when they had to stay dark.

But perhaps the most surprising thing about Bumbershoot’s three-year hiatus is that initially it was not pandemic-related.

Former producer AEG announced it was stepping away from Bumbershoot in late 2019, long before COVID landed. Other music festivals were folding in the years before the pandemic, due to a glut of similar events and skyrocketing talent prices for bands. When the pandemic was thrown on top of those trends, the possibility of Bumbershoot coming back seemed remote.

That challenge appealed to Severin, and his partners Lundgren and Paganelli. So, in 2021, when the city put out a call for proposals for revamping Bumbershoot, the trio jumped and won the rights, with renewal options, for the next 15 years.

“It was a chance to work on something that I’ve always loved, something that is so deeply rooted into Seattle itself,” Severin said. “You’d have to be a little crazy to tackle something like this. Thankfully I had two other people of the same ilk who have different skill sets than me.”

Among Severin’s first tasks was to focus on ticket affordability — one of the main complaints from past attendees, the elders of whom loudly yearn for the old days “when it was $10.” (Few of the complainers on social media acknowledge just how expensive it is to pull off a successful city center festival.) To do that, he approached a local business: Amazon.

“I basically went to them,” he recalled, “and said, ‘You’ve got the chance to do a really good thing,’ and they did it.” Amazon’s commitment is for one year, which along with a large gift from Ballmer Group’s foundation and a few others, helped make the lower ticket prices possible.

Even so, Severin is almost certain this year’s Bumbershoot will lose money. “Only 70 percent of our expenses are coming from ticket revenues,” he said, “so the need for sponsorship is huge.”

He hopes those losses will be offset by future years, and by creating generations of Seattle residents who take ownership in the festival as part of Seattle’s cultural legacy. Maybe some local company, foundation or wealthy arts-loving individual will step up with an endowment that would keep Bumbershoot healthy, he posits.

It’s not unheard of: San Francisco’s popular Hardly Strictly Bluegrass festival is supported by the endowment of venture capitalist Warren Hellman (and is booked by Chris Porter, who for years was responsible for Bumbershoot’s music lineup).

“An endowment of $30 million, which sounds like a lot, but really is a rounding error for many of the wealthy in this region … would keep Bumbershoot going for years to come,” Severin said. “It would bring an immeasurable amount of goodwill and love towards whoever steps up to fund such a thing. You can’t buy that kind love with just money usually, but here you could.”

In Severin’s mind, the festival is already a win simply because of how it has been repositioned and expanded. That includes an education program created to train kids in the industry, which has already worked with 16 young people from underserved communities.

Barbara Mitchell worked on Bumbershoot for a decade during the era when One Reel produced the event and knows just how hard it is to pay the festival bills. But she’s optimistic in part because she believes Severin and New Rising Sun have returned the festival to its roots.

“What I loved the most about Bumbershoot was that it had eclectic and fun arts stuff,” Mitchell said. “And Steven has booked the acts and events that will create that again. There’s something billed as a ‘Cat Circus.’ I have no idea what the Cat Circus is going to be, but I’m totally in just on the very idea of a Cat Circus.”

Organizers were willing to reveal that the circus “features a crew of rough, tough and sweet felines … performing, or maybe not performing, death-defying acts including tightrope walking, a ring of fire, the ‘cat cannon,’ and many more impossible stunts.” But as with other unusual acts on the roster, the lack of advance intel is intentional. “Discovery” and “mystery” are two words that came up often when Severin talked about the vision for the new Bumbershoot.

This year’s musical lineup is also unusual compared to other festivals. “Two thirds of the artists are BIPOC, LBGTQ, or female,” he said. “We made it diverse, and over half of the artists are Northwest-based.” Regardless, the long Seattle tradition of whining about the lineup — who’s included, who’s left out — commenced the moment it was announced on social media.

Nonetheless, Severin insists, “Even before it starts, we achieved a success by making it be about Seattle, for Seattle, and by Seattle.”

Bringing back visual and performance art as a major component of the festival — “and not as a little side piece” — is another achievement Severin touted. “Greg Lundgren said he was tired of starving artists, so we paid creative people to make art,” he said. “We’ve put zeros behind budgets I’ve seen from previous Bumbershoots to put money into artists’ pockets.” Some of the new sculptural exhibits will be staged among the reflecting pools at Pacific Science Center, including a 1970s style “conversation pit.”

“For anyone who loves art, loves music, and loves Seattle, this is going to be their favorite Bumbershoot,” Severin said.

My own favorite Bumbershoots are memorable more for personal reasons than professional. No memory is sweeter than watching my son, then a teen in 2014, run to the front of the Memorial Stadium stage and slam-dance to the Replacements reunion.

That’s the thing that a city-owned festival in the center of town does for residents of Seattle: People feel a kind of ownership around Bumbershoot.

Seattle illustrator Frida Clements said her fondest festival memories are also related to family. She remembers attending when it was free when she was a child. In later years, she worked at the festival as a graphic designer involved in the Flatstock poster exhibit (which returns this year). Clements said she got the most out of it when her kids joined her on the grounds.

“After the vendors closed up, we all got to see some great bands together,” she recalled. “It was bonding, and lovely to look up at the stars past the Space Needle, and hear all the sounds with my babies, and do it within art and music.”

It is that sense of community and joy in music and art that frequent attendees cite as what’s special about Bumbershoot, alongside the chance to see your new favorite band. “I remember how many great new bands I was exposed to at the 2014 festival,” local music fan Cynthia Setel said. “Hearing Gregory Porter for the first time, dancing with a crowd to Bomba Estéreo. The festival is about bringing together the famous with the should-be-famous in a joyful, appreciative setting.”

For local bands that perform, Bumbershoot is a hometown show, in front of hometown fans. Severin said he went out of his way to book bands with Seattle connections this year, to give the festival more of the feeling it had in the 1980s, when it served as a launching pad for groups like Soundgarden, the Screaming Trees and other later legendary acts.

“I knew that Band of Horses just had to be there,” Severin said of this year’s roster, noting, “a lot of bands involved took less money than they would for other shows because they too want to support what Bumbershoot means.”

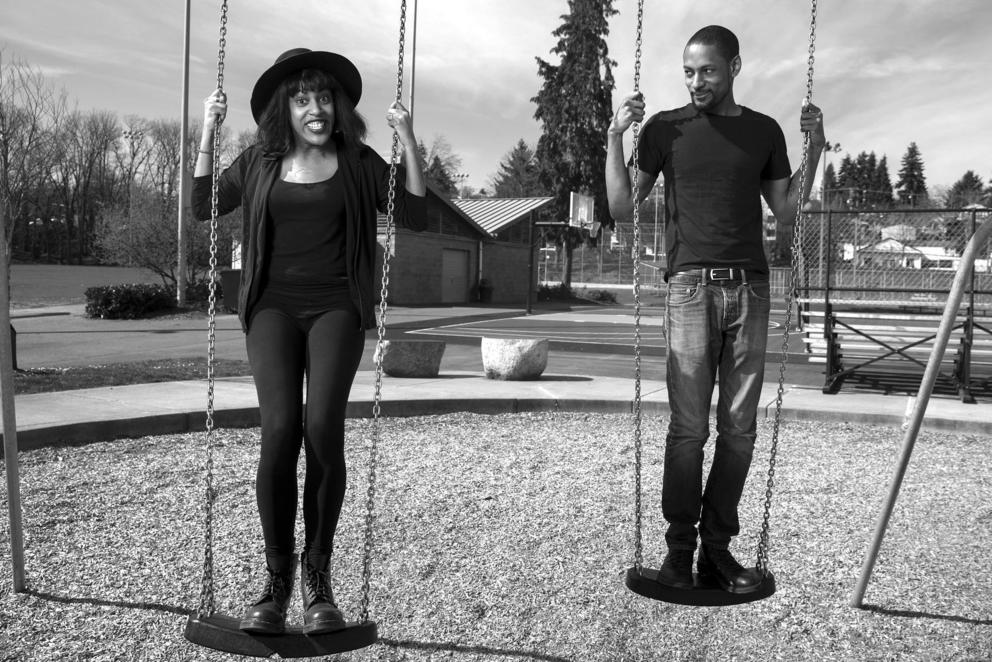

Eva Walker of The Black Tones is also on the bill this year and is one of those Seattle musicians who was shaped by Bumbershoots past.

“My favorite show ever was the Wu-Tang Clan,” she said. “To me, the festival has always been about local favorites, national headliners and surprises,” Walker added. “And to play there as a musician, it’s a bucket-list event. We feel honored, and we’re gonna do everything to make sure Bumbershoot sticks around for years to come.”

Then Walker added a surprise of her own. “I’m pregnant now, and I want my child to grow up just like I did — getting exposed to the magic of Bumbershoot.”

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.