There have since been some standout shows: Jeeves Takes a Bow at Taproot Theatre; Sound Theatre’s poignant caregiving drama Cost of Living; ACT’s Sweat by Lynn Nottage; The Intiman Theatre/Williams Project’s co-production of The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window by the late Lorraine Hansberry.

But instead of a stampede to the box office, theaters are seeing ticket sales rise slowly — and not nearly up to pre-pandemic levels. Just as dispiriting, necessary donations are lagging too.

Shock waves struck in late June when Book-It Repertory Theatre, a unique and beloved Seattle troupe that specialized in adapting literary fiction, folded due to fiscal shortfalls.

That sad news came on the heels of an emergency $7.3 million fundraising drive to keep the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland — the largest, oldest resident theater in the Pacific Northwest — from having to cancel its current season. (There was a collective sigh of relief this month when that goal was met.)

The fragility of nonprofit theaters isn’t just a problem in this part of the country.

In a recent Washington Post story with the scary headline “Theater is in freefall,” drama critic Peter Marks wrote that factors beyond the pandemic have led some major regional companies (L.A.’s Mark Taper Forum, Lookingglass Theatre in Chicago) to postpone their next seasons. Some smaller outfits (Southern Repertory Theatre in New Orleans; Actor’s Theatre in Charlotte, N.C.) are shuttering permanently.

And a New York Times survey of 72 top-tier regional theaters warned of “a crisis in America’s theaters,” estimating that 20% fewer productions will be staged in the 2023-24 season than in the last full season before the pandemic.

If any business loses, say, 20 to 30 percent of its income and capital, it’s rough. But theaters operate so close to the bone, such loss can be catastrophic.

So what has gone wrong for these once-vibrant cultural institutions? And what needs to happen for the long-running, well-regarded Seattle theater industry to survive and rejuvenate?

Here’s what regional theater leaders say about the challenges to recovery, and five strategies to save an essential cultural amenity.

Turn the next generation into avid theatergoers by wooing a younger crowd.

This has been a pressing concern for regional theaters in recent decades, due to the “graying” and eventual loss of frequent subscribers and ticket buyers of retirement age and beyond. Attempts to address this audience drop-off are very much a work in progress.

Seattle Rep, for instance, has made serious efforts to reach out to some of the thousands of under-40 tech workers who have settled (at least temporarily) in the area in recent years.

“During our 2022-23 season, we invested in advertising via outlets geared toward tech professionals,” says the Rep’s director of strategic communications Melissa Husby. “With the leadership of a trustee who works for Google, we also held an in-person and live-streamed lunchtime panel on Asian Americans in the Arts on Google’s South Lake Union campus, featuring several local artists.”

For the coming season, Husby notes, “we are expanding our advertising with tech-specific outlets, holding an on-site visit at the Microsoft Commons, identifying new opportunities to engage in artist talks or lunches at local tech campuses, and developing additional ‘Built by Seattle Rep’ behind-the-scenes content geared toward a tech audience.”

But it has not been easy to entice large numbers of tech workers to catch the theater bug. Stage productions must compete for attention with the immense popularity of video games, Hollywood action movies, sporting events and other pastimes with strong appeal — and far bigger advertising budgets — for this demographic.

Asking private and corporate funders to underwrite ticket deals for people in the 20- to 30-year-old range could help draw younger viewers — who would ideally come to the next show with friends in tow.

And thinking even younger: Support for school-based arts education is essential. Far more families, too, could take advantage of the TeenTix organization, which offers adolescents aged 13 to 19 $5 tickets to plays and musicals (as well as classical and modern dance and music concerts, operas and museum shows).

Mounting productions that may appeal to a wider age spectrum could also be helpful, suggests Seattle Rep managing director Jeff Herrmann.

“We’re really emphasizing opportunities for families to attend together,” he says, “with show-by-show age recommendations for kids and teens.” These include this season’s free musical version of Shakespeare’s The Tempest (Aug. 25 – 27), as well as a fresh adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women (Nov. 10 – Dec. 17), modernized with contemporary feminist notes by playwright Kate Hamill.

Entice former single-ticket buyers off their couches — and away from streaming services — to see live theater again.

As The Williams Project artistic director Ryan Purcell puts it, people who used to catch a show now and again have “gotten out of the habit” since the pandemic closures.

One tactic Taproot artistic director Karen Lund employs: getting her company more involved and visible in the surrounding Greenwood community. “We’re leaning into our neighborhood more,” she says.

“Greenwood is changing. There are a lot of big apartment buildings going up, and some are using cultural amenities like Taproot as a selling point for prospective renters. So we’re joining in at the art walks, the festivals, the other neighborhood events in our area.”

But for many theater administrators, attracting people back into the fold is fairly fundamental.

They believe they can renew the public’s faith and interest in what they’re doing only by offering quality artistic experiences via excellent acting, compelling scripts and strong direction. Despite the rising costs of living that have priced some arts workers out of the Seattle area, there is clearly the talent here to make great theater.

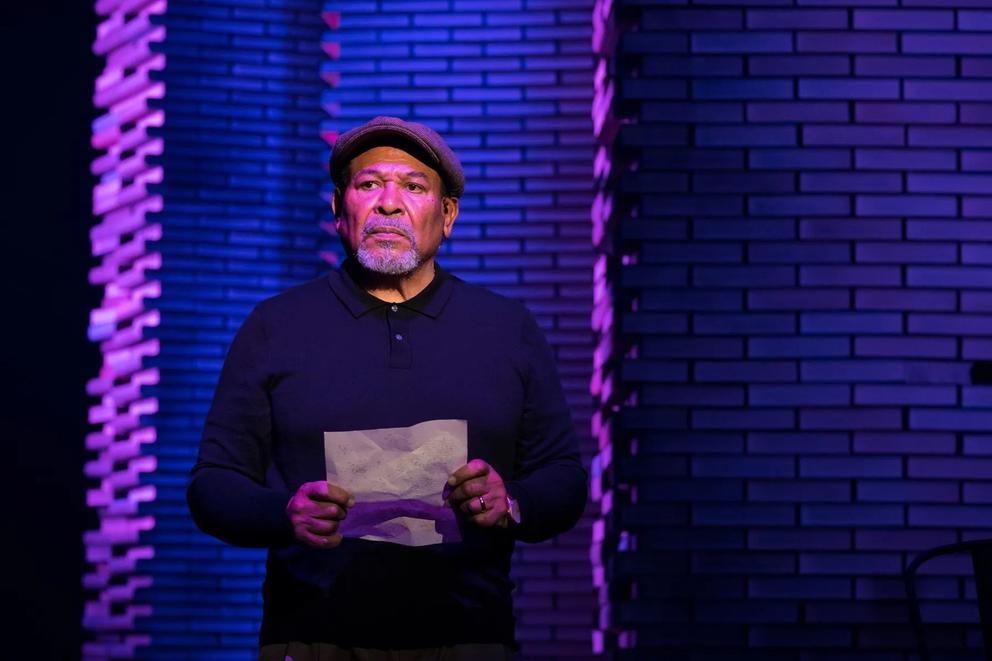

“The way forward is getting back to why people want to see plays, what that visceral experience is,” says Dámaso Rodríguez, the incoming artistic director of Seattle Rep, the city’s largest resident playhouse.

He advocates for large-scale, large-cast productions that make a lasting impression. “When I interviewed for the Seattle Rep job,” says Rodríguez, whose previous post was running Artists Repertory in Portland, “I wasn’t shy about some of the things I want to do, in terms of scale of work.”

But there are other ways to “go big” if the financial reach of a large-scale production is too risky.

Next spring, ACT will present the Seattle debut of The Lehman Trilogy (Apr. 26 - May 12) an epic saga charting the rise and fall of one of the country’s largest investment banks before its shocking demise in 2008. The Broadway version of Italian author Stefano Massini’s play (adapted into English by Ben Power) earned five Tony Awards. One source of its lauded theatricality: Three actors portray more than 50 roles in a script covering 170 years.

Locally, The Williams Project has made another kind of splash by reviving plays by well-known American and British authors, casting polished actors from around the U.S., and touring them to nontraditional, real-world spaces: a school cafeteria, a church, a community center, a park behind a library.

Purcell feels it is important to bring theater to places where people congregate for other reasons. Another necessity: Articulate and commit to a specific artistic mission.

“What theaters sometimes do is they say, we’ll do a show for this or that group, hoping they’ll come back for the other shows,” he says. “For that to work there has to be a steady level of aesthetic excellence.”

Make tickets broadly affordable — while meeting rising expenses for actor and staff pay, scenery, costumes and other essentials.

With artistic budgets increasingly tight, theaters can’t always offer bargain-basement pricing. But tickets to high-quality theater in Seattle are not as costly as people may assume.

Many companies offer substantial discounts to youths, seniors and groups as well as pay-what-you-can previews. And while the most expensive shows can seem pricey, it’s all relative to what you’d spend on any night out with live entertainment.

A top ticket to the well-received musical The Hello Girls (extended through Aug. 19) at Taproot is $46, with discounted options from $15 to $41. The tariff for the upcoming, nationally praised Cambodian Rock Band at ACT (Sept. 29 – Aug. 5) tops out at $89 for the best seats on a Saturday night but significantly less on weeknights.

Many people will happily pay a premium to see a Broadway touring show (even if they’ve seen it once or twice before) while passing on an excellent locally produced play or musical that costs far less. But the hyping and marketing of Broadway blockbusters is far more prevalent than for homegrown productions.

It is incumbent upon local theaters to get the word out about ticket deals, but also about the level of talent they’re putting on stage. A surprising number of Seattle actors have appeared in such A-list tours, and on Broadway itself.

Theaters must also find creative ways to communicate why it would be entertaining and maybe even illuminating to see a pop musical like Cambodian Rock Band — a rousing jam of live rock music, humor and Southeast Asian history.

How do they do that without hefty ad budgets? And with fewer media outlets publishing theater previews and reviews? Some theaters are looking into co-op print and online advertising plans and other collaborative measures like two-fer ticket packages for multiple theaters.

Retain and/or win back older theater loyalists, who worry about COVID-19 transmission or say they’re turned off by recent theatrical programming.

Given the pandemic closures, theaters are highly concerned with safety for their patrons and performers. But masking is no longer mandatory at most local theaters.

At a recent 5th Avenue Theatre show, I saw maybe one masked person in 50, in a theater that can seat about 2,000. In smaller venues, masking has been at a higher ratio but still sparse. With elders at a higher risk for COVID complications, this has kept some loyal theater fans away.

While statewide mask requirements have loosened, several theaters have started offering special performances during which all audience members must be masked, including at Seattle Rep’s The Tempest (Aug. 25) and Intiman’s upcoming Cindy of Arc (Nov. 1). Sound Theatre has “all vaccinated” performances of Autocorrect Thinks I’m Dead (Sept. 10 and Sept. 22). Such options could make concerned theatergoers feel more secure.

As for programming, that is a very sensitive and to some degree subjective topic. In recent years theater has undergone a social justice “reckoning,” with artists of color, nonconforming genders and different abilities demanding more inclusion in casting, theater leadership and choice of material.

Great strides have been made in some of these areas, in Seattle and elsewhere. But the changes have come with complaints too — including from longtime subscribers — that in a desire to rectify persistent inequities, companies have presented too many didactic works or sacrificed quality for so-called political correctness (or, as several commenters on a recent Seattle Times story about the demise of Book-It put it, “preachiness.”)

Few if any theater workers believe it is time to turn back the clock and return to a field largely dominated by white leadership and performers. Nor do they want to steer clear of timely and controversial subject matter for fear of causing offense.

But in online comments to multiple theater stories in The New York Times and The Seattle Times, some former theatergoers have decried a rising level of political stridency that they say is keeping them from resuming their patronage — especially when it is not matched with high-level artistry.

Purcell says his thinking on the matter is complicated. “There is a difference between great art that has a political agenda, and art that’s built around preaching a political agenda,” he says. “We did Blues for Mr. Charlie, by James Baldwin, a very political play. It asks white America what’s gone wrong to allow so much hatred and injustice in our country. But it’s also a killer piece of writing.”

He adds, “Sometimes I think there’s a form of theater-making right now that starts out already knowing the answer. I only want to work on plays that ask questions there’s not a simple answer to.”

Find the necessary income in a shifting fundraising climate and advocate for more governmental arts funding.

This may be the biggest hurdle theaters are facing. After all, even Broadway shows require theater-loving, deep-pocketed backers to underwrite commercial productions — many of which never show a profit.

And nonprofit theater is a sociocultural force which, as a labor-intensive business, has always needed underwriters to stay afloat. (Consider Shakespeare’s reliance on British aristocrats to foot the bills.)

But today no American city can expect the kind of generous support from government, corporations, and wealthy private individuals that kept the arts humming here during the 1980s, ’90s and early 2000s (in Seattle, for example, the Benaroyas or Kreielsheimers). And some of Seattle’s largest corporations contribute very little or nothing to the arts.

With rising social inequities, today’s philanthropists and municipalities are understandably called to aid the homeless and hungry and to bolster public education. Which means advocacy for arts funding (usually a fraction of the dollar amount social welfare programs require) is much needed.

Recently arts advocacy group Inspire Washington lobbied the state legislature to pass House Bill 1575, which allows counties and cities to create their own “cultural access” discount programs (using sales or property taxes up to .01%) by council or commission votes. Gov. Inslee signed it into law in April.

Even with this positive development, streamlining expenses is essential for theaters’ future survival.

Some have already come up with creative solutions: The long-running Intiman Theatre is in its third incarnation, now as the resident company and theater-education resource at Capitol Hill’s Erickson Theatre, a part of Seattle Central College.

Other companies are shortening the runs of productions to improve the bottom line (though that can mean, in the short term, less employment for theater workers).

Taproot has gone from a standard six-week run to five weeks. But if the production is a hit (“We used to routinely sell more than 90 percent of our seats,” notes Lund, “but now if we sell 78 percent, we’re calling it a hit”) they’ll extend it a week — to what used to be a regular run.

And companies could also max out the prospects of collaborating with one another on joint productions, advertising and other expenses.

“I think the theater community can and should be looking for more opportunities to partner and share resources,” says The Rep’s Herrmann. “It’s always been a pretty collaborative and supportive community, especially here in Seattle, and we may need to go even further in this direction during this recovery period.”

But after all the collaborating, strategizing and rejiggering, the proof will be in the pudding. As Purcell emphasizes, if theater is to thrive here, it must justify its artistic worth.

“We need to focus on getting the quality back, giving the artists the time and resources they need for that,” he says. “It sounds paradoxical, because in an industry that survives on donations, you have to make that case to donors through your shows.”

If local organizations make first-class theater, will they come — the old audiences, the new ones and the donors too? That’s the great, and perhaps only, hope.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.