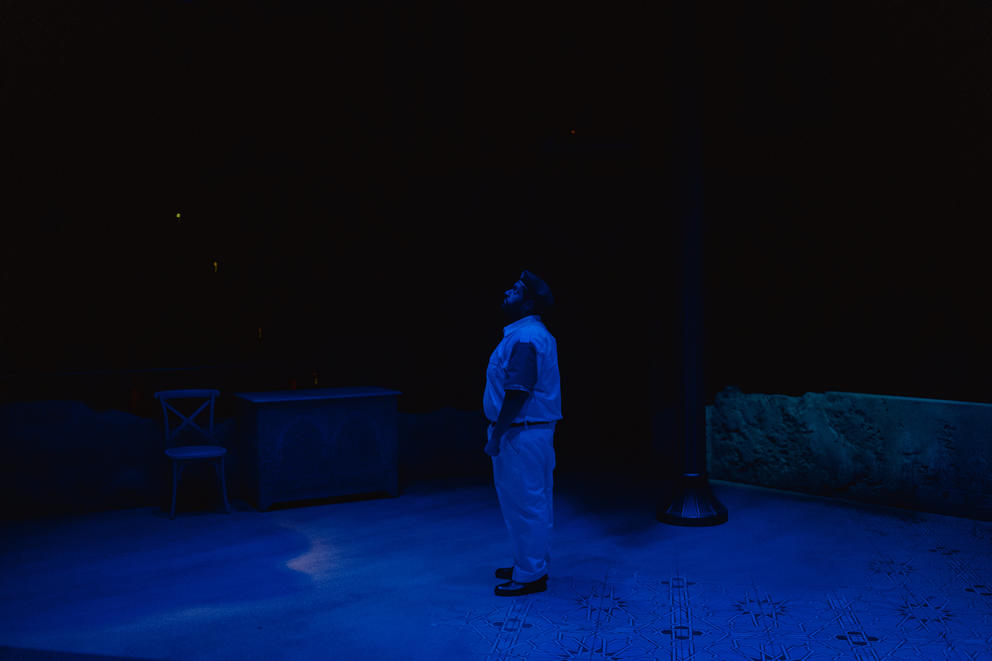

Such questions arise for two couples — one American, the other Egyptian — whose lives intersect in Hotter Than Egypt, a new play by the award-winning Seattle playwright Yussef El Guindi. Set in Cairo, the world premiere play is on stage now at ACT Theatre (through Feb. 20), under the direction of ACT’s artistic head, John Langs.

Cross-cultural tensions between Middle Eastern and Western characters is a theme El Guindi explores in many of his highly regarded, engaging, shrewdly observant and thought-provoking plays. And that is because El Guindi knows, intimately, what it is to be a stranger in a strange land — to have roots in one part of the world and be a citizen of or voyager to another.

“It is impossible for me to not see both sides — inside and outside,” he says. “I was brought up in England, and whenever I came to Cairo to see family, I was slightly an outsider, and when I came to America also. I think I’ll always be writing about outsiders negotiating with the places they’ve wandered into or chosen. It’s just baked into my gut.”

A longtime Capitol Hill resident, El Guindi appears to be settled in Seattle and the U.S. (where he has gained citizenship). But given his broad worldview, it is not terribly surprising that his plays often explore — in nuanced, unpredictable, sometimes humorous ways — the uncomfortable and consequential dynamics among people longing to communicate with one another across a gulf of differences.

“Relationships in general are of interest to me,” he says. “We’re strangers to each other; we’re trying to make bridges to one another. Everyone’s a bit of an island, trying to make connections to others and awkwardly stumbling toward those connections.”

Born into a distinguished Egyptian family, educated in England and America, El Guindi has lived in the U.S. since 1983, and has forged theatrical success here, by any measure. More than a dozen of his plays have been staged with distinction in Seattle, New York, Portland and other cities, as well as abroad. He has earned coveted honors, including two play prizes from the American Theatre Critics Association and a Middle East America Distinguished Playwright Award. And in 2019 Bloomsbury/Methuen published a five-play anthology of his work.

In a review of that book, theater and literature scholar Areeg Ibrahim wrote, “Like so many twenty-first century ‘hybrid’ Americans, Yussef embodies the spirit of hailing from both ‘here’ and ‘there,’ of belonging to both ‘us’ and ‘them.’ He defines the who, what and where, and adheres neither to outdated binaries, nor borders, nor the dictates of a melting pot.”

In one of El Guindi’s most produced plays, Pilgrims Musa and Sheri in the New World, which premiered at ACT Theatre in 2011 and has since been performed around the U.S., an American waitress and a Middle Eastern immigrant cabdriver gradually acknowledge and navigate what separates them. And in doing so, they find their way into a heartfelt romance.

Hotter Than Egypt sets up a different, more politically and sexually divisive dynamic. In this tale, a well-heeled married American couple has a fraught encounter with a younger, financially strapped Egyptian pair serving as their Cairo tour guides. In both oblique and obvious ways, what transpires over two days will impact all of their futures.

The play’s bickering Wisconsinites, Jean (portrayed by Jen Taylor) and Paul (Paul Morgan Stetler), are hoping their first-class trip to a picturesque Mideast capital will rekindle a marriage that has clearly gone cold — particularly for the unfulfilled Jean. Their guides have their own troubles: Maha (Naseem Etemad), a seasoned guide who obligingly shepherds foreigners around Cairo, yearns for an economically better, less difficult life than seems possible in Egypt. Her more cynical, unemployed fiancé, Seif (Wasim No’mani), is begrudgingly trying to learn her trade — for which he is temperamentally unsuited.

Whether they are debating if it is culturally insensitive to wear a bikini in an Arab country or the differences between a democracy and theocracy, and whether they are conversing in English or in Arabic (which is cleverly translated for an English-speaking audience), the foursome’s attempts to comprehend one another can be laughably tone-deaf and deeply frustrating.

But in a twist best not revealed as a spoiler, the second half of the play sees a shift in the four-way chemistry. The play becomes more about the magnetic attraction of the Other, and the fantasy of impulsively escaping into a new, “exotic” culture or relationship.

As Seif, Los Angeles-based, Iraqi American actor No’mani aces the play’s most trenchantly witty — yet ultimately most humane — character. No’mani was also a standout in El Guindi’s The People of the Book when it debuted at ACT Theatre in 2019, and feels in tune with the playwright’s vision.

“What makes performing El Guindi’s plays so challenging and rewarding,” No’Mani says, “is also what makes them so deceptively accessible. On the surface, the text appears to be very logical and straightforward, but it is filled with layers of emotional and political subtext that makes sinking your teeth into [it] so gratifying.”

Hotter Than Egypt acquired those layers a decade after the playwright’s first draft. “I wrote a number of plays that were in response to the 2011 Egyptian Revolution, and began this one in 2013,” explains El Guindi. “At that point, when I’d visited relatives in Egypt, I did not know how things would turn out there after the uprising. But I wrote it with a hopeful resolution and put it away. Later, as the progress made during the revolution receded, and a new dictatorship developed, I kept feeling I should return to it.”

During the pandemic, travel was limited, but the condition of his native country was still on his mind. It seemed to El Guindi like a good time “to stop sitting on my bum” and finish the script. He incorporated the stifling of dissent and poor economic conditions, as well as the beauty and antiquity of Cairo, into the backdrop of Hotter Than Egypt. But the story focuses most intently on personal journeys (literal and metaphorical).

“I always say that playwrights are not reporters,” El Guindi notes. “Some news item may trigger a play, but very often what is triggered is something universal. This play is about what happens to these individuals in a personal vortex, a crisis that is also operating in a larger political context.”

That context is most immediate for the Egyptian characters. “Seif is a would-be father and husband, had he not been stifled by the political and economic climate in Egypt,” No’Mani reflects. Instead, he is trapped in “waithood … a term coined specifically for an elongated period prior to proper adulthood in Egypt, as impoverished men and women wait to start their own life.”

For Seif, black humor is a weapon against despair, in a homeland he can barely survive. “Being fed up is the air we breathe in this country,” he tells his partner, Maha. “What if we're struggling? Poverty is in. It's all the rage these days. We're part of a fashion trend.”

But beyond the sarcasm, there is love and loyalty. “What I found so moving in Seif’s journey,” adds No’Mani, “is his selfless sacrifice for the one person he loves the most. This action to lift others even at the cost of what one wants has always been inspiring to me.”

Conversely, for the economically privileged Jean, it’s her so-called “perfect” American life that is oppressive — and which she longs to break out of in her own rebellion.

“Jean’s character arc is enormous and that is a big, scary challenge,” says Taylor, a veteran Seattle actor. “She ends the play in a drastically different place from where she begins. She finds herself behaving in ways and in situations which she couldn’t earlier comprehend.”

Granting his characters complexity, ambivalence and the ability to evolve — in front of a live audience — is an aspect of theater El Guindi holds dear. While many of his peers have transitioned from playwriting into the more lucrative field of screenwriting for film and TV, El Guindi (who is a member of ACT’s Core Company) is still laser-focused on writing for the stage, despite the enormous hit that live performance has taken during the pandemic. And he hopes that audiences for live drama will return and grow as the pandemic recedes. Once again, it comes down to communication.

“If you watch a movie, it is absolutely indifferent to your presence,” he says. “Live theater is a dialogue. People appreciate the immediacy, the engagement, the participation. The actors are performing, but so is the audience. I think the desire for that thing will never go away.”

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.