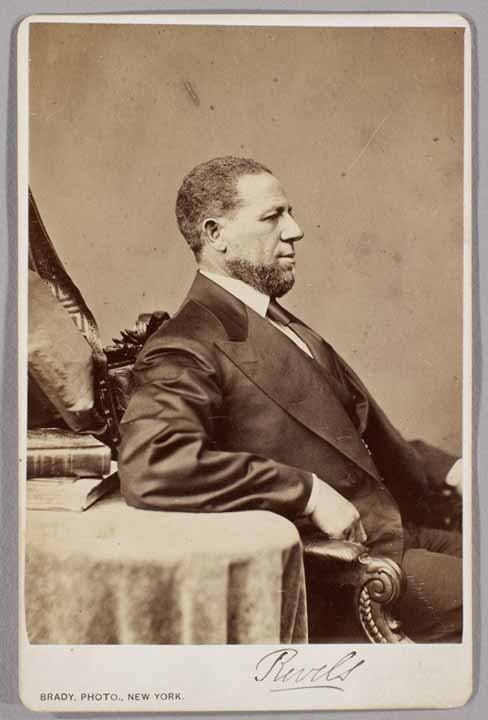

It’s a portrait appropriate for a man of his standing (taken by Matthew Brady, who photographed 18 American presidents, including Abraham Lincoln). Under Revels’ influence, a former pupil moved to Seattle to publish the Seattle Republican, a Black-owned newspaper that became one of the most well-read in the region at the turn of the 20th century.

The fact that this historical thread is unknown to many today illustrates the underlying mission of the Kinsey collection: to remind us that Black narratives are central to the American past, yet are often overlooked in plain sight.

On view at Tacoma Art Museum (July 31-Nov. 28), the Kinsey collection celebrates the achievements and contributions of Black Americans from 1595 to the present with an astonishing array of more than 150 photographs, paintings, sculptures, rare manuscripts and documents that expand our perspective on the nation’s history and culture.

“African Americans are ‘invisibly present’ in America,” Bernard Kinsey explains in a video conversation with TAM about the family’s collection. “Art is the highest form of communication and one of the few things that can make the invisible visible. Seeing the collection changes your ideas about who you are.”

Shirley Kinsey, Bernard’s wife of 50 years, remembers it was that need to know who they were that first drove them to collecting. When their son Khalil (who today curates the Kinsey Collection) was in the third grade, he was assigned a family history report, which was when they discovered the family had very little ancestral information. The legacy of slavery, prejudice and institutional racism meant records were scant, missing or incomplete. “I decided we would look at our collective ancestry instead,” Shirley recalls in the video.

“Landscape, Autumn” (1865), at left, by Robert Scott Duncanson, a significant contributor to the Hudson River School, and “Parisian Cubism” (1927), by Hale Woodruff, who also drew political cartoons for Black-owned newspaper the Indianapolis Ledger. Both oil paintings are included among the works by Black artists in the Kinsey collection. (Tacoma Art Museum)

The family began researching and seeking out objects, original art, artifacts, and historical documents that gave voice and expression to obscured and often untold stories of African American achievement and contribution. Fiercely committed to sharing the full narrative of our nation’s history, the collection is not restricted by medium, and pieces are both by and about Black Americans.

“African Americans participated in every aspect of American life, but most of what we talk about is manual labor with cotton and sugar cane and tobacco, when in fact that was a very small part of the contributions,” adds Bernard.

Pursuing this idea has blossomed into a collection that is considered today to be one of the most comprehensive surveys of African American history and culture outside the Smithsonian Institution.

Now in its 15th year, the collection has toured 30 cities in the U.S. and internationally, including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, and most recently the Greenwood Cultural Center and Gathering Place in Tulsa, Oklahoma, as part of events marking the 100th anniversary of the Tulsa Race Massacre.

What is unique about the Kinsey Collection is its massive timeline, starting with a 1595 baptismal record of a young enslaved girl in St. Augustine, Florida — 12 years before the first English settlement in the Americas — all the way to a mixed media abstract piece created in 2005 by Sam Gilliam, a major contributor to the Color Field School.

There are rare, intimate glimpses of iconic Black Americans, such as five letters written by author Zora Neale Hurston in 1942, as well as a letter Malcolm X wrote to Roots author Alex Haley two years before Malcolm X was assassinated.

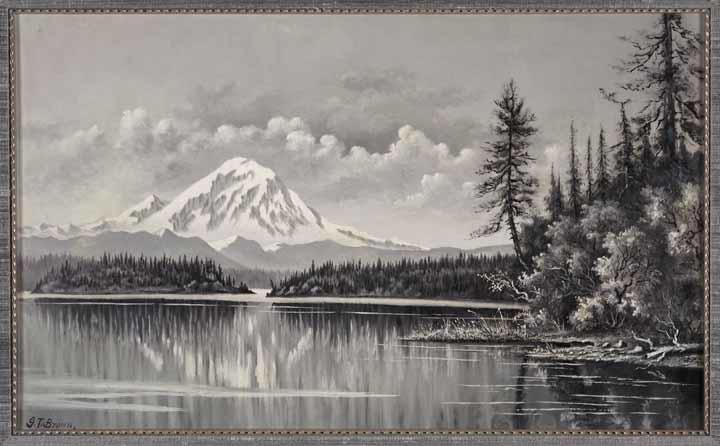

“Mt. Tacoma from Lake Washington,” an 1885 painting of Mount Rainier (then called Mount Tacoma) by Grafton Tyler Brown, now recognized as the first Black American to depict the Pacific Northwest on canvas. The piece is one of many accomplished artworks by lesser known Black Americans included in the Kinsey Collection. (Tacoma Art Museum)

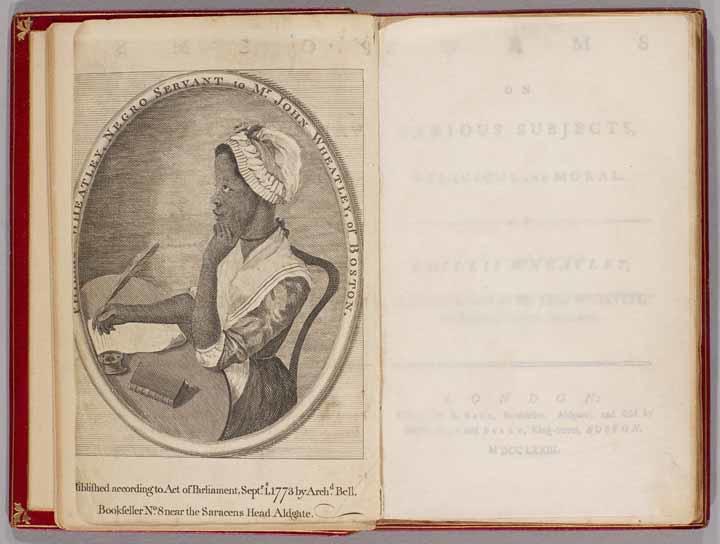

The collection also includes works by and about Black Americans everyone should know about: an 1885 oil painting of Mount Rainier (then known as Mount Tacoma) as seen from Lake Washington by Grafton Tyler Brown, now recognized as the first Black American to paint the Pacific Northwest; a rare first edition of a 1773 book of poems by Phillis Wheatley, the third book of poetry to ever be published by an American woman; and an ethereal autumn landscape painting from 1865 by Robert S. Duncanson, an artist whose work First Lady Jill Biden selected to be on view in the Capitol.

And the presence of anonymous individuals is also felt strongly, by way of artifacts such as a letter of sale delivered by a young girl about to be separated from her parents. This knowledge, too, might otherwise be lost to history.

The Pacific Northwest is no exception to this theme. An essential narrative line from Seattle’s own history was nearly lost were it not for a few scraps of paper discovered in the 1990s in the attic floorboards of an old home in Capitol Hill. The yellowed, handwritten receipt from a dry goods store and a marriage certificate were both signed by none other than Hiram Revels. The papers had literally slipped through the cracks.

It turned out the home once belonged to Revels’ daughter Susie, who moved from Mississippi to the Pacific Northwest to marry her father’s protege, Horace Cayton. It was Cayton — an emancipated college graduate — who published the groundbreaking Seattle Republican (1894-1913). When Susie Revels Cayton became an editor in 1901, she also became the city’s first female journalist, though she was never recognized for it.

Just this past spring, the city of Seattle officially landmarked the Cayton-Revels House — more than 100 years after the family lived there. (Full disclosure: I wrote the landmark nomination application.)

At TAM, the Kinsey exhibit will include a few items never been shown before, including a parade flag from the late 1880s that belonged to the all-Black infantry regiments of the U.S. Army known as the Buffalo Soldiers, as well as a letter written by famed 20th century painter Jacob Lawrence, in which he describes his first year living in Seattle. Because of the constant rain (about nine months out of the year), he writes, it remains green and lush year round.

The show doesn’t necessarily thread these stories together — that is left to each viewer. “Because the exhibit is made up of primary sources, we don’t feel the need to interpret or interpolate,” Khalil Kinsey says in the TAM video. “You’re going to come to certain understandings on your own. This is a human story that anyone can see themselves in, no matter what they look like or where they come from.”

Here in the Pacific Northwest, we are still on a journey to learn the full experiences of our shared heritage.

We know Seattle’s first Black American resident, Manuel Lopes, arrived in the territorial era in 1858 and established one of the city’s first barber shops, on First Avenue South. Much more recently, in 2005, the Washington state Legislature formally voted to make Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. the official namesake of King County (which had been originally named in 1852 after Vice President William Rufus de Vane King, an enslaver and advocate of the Fugitive Slave Act).

A monument to Confederate soldiers of the Civil War erected in Seattle’s Lake View Cemetery in 1926 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy was toppled in 2020, amid the protests in response to George Floyd’s murder.

Organizations like the Black Heritage Society of Washington and the Northwest African American Museum are working to chronicle, preserve and celebrate the cultural legacy of the region. With broader education and awareness, we can begin to question what has been omitted from the narrative and appreciate what has been in front of us all along — with acknowledgments such as the recent formal recognition of the Cayton-Revels’ contributions to journalism and civil rights in Seattle.

“We actually were not aware of the connection between Hiram Revels and the Pacific Northwest,” Khalil told me, after I mentioned it during a phone interview. “I am blown away, but also not surprised,” he said. “What we’ve learned and continue to learn is that these connections are everywhere and all around us.” Based on this information, he plans to rewrite the label on the Revels photograph. “This is a history that is shared among all of us,” he said, “and it continues to unfold and illuminate the story.”

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.