Historian Quintard Taylor, professor emeritus at the University of Washington and founder of Blackpast.org, says Horace Cayton Sr. was “by far the most prominent African American in the Pacific Northwest in the first decade of the 20th century.” Cayton was an influential publisher whose newspaper, the Seattle Republican, was said to be the second-most read in the city in its 1890s heyday, with a largely white audience. Cayton was also active in Progressive-era Republican politics, one of few Black men allowed into the state party’s inner circle.

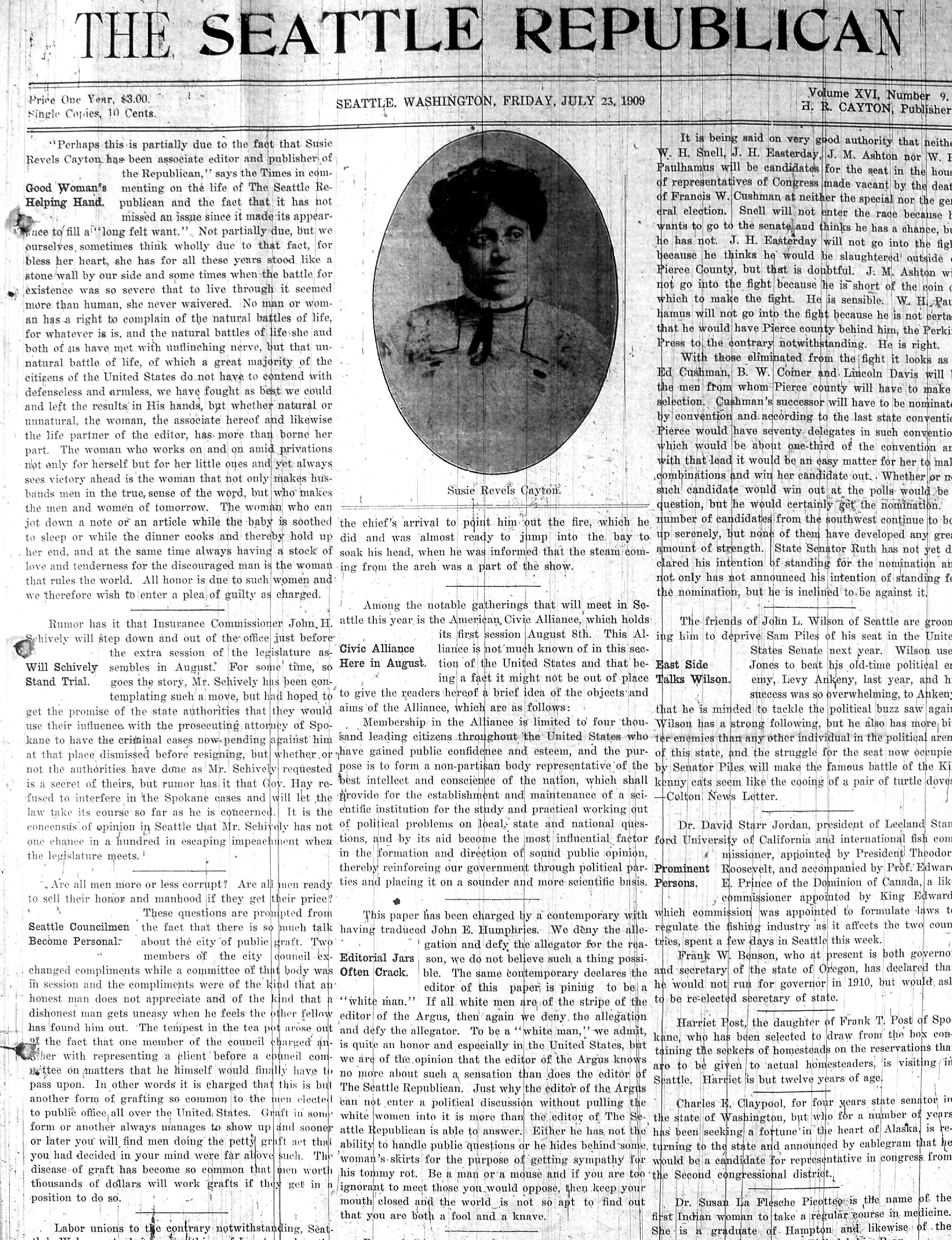

Susie Revels was his publishing partner. One of the first, if not the first, female editors in Seattle, she wrote for and edited the Republican, and played a prominent role in Seattle’s growing African American community. Her father was Hiram Revels, the first Black U.S. Senator, elected to Jefferson Davis’ former Senate seat in Mississippi during Reconstruction. Husband Horace, meanwhile, was born into an enslaved family. He eventually achieved a college education and came to Seattle for a job at the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

The Caytons prospered in the days before Seattle was heavily redlined and segregated. They lived from 1902 to 1909 in a comfortable home at 518 14th Ave. E., near the intersection of East Republican Street, then one of the city’s more tony neighborhoods. The home still stands in much of its original condition.

The current owners, Erie Jones and Kathleen Ackerman, fully support the landmark nomination. Much of the interior is the same as it has always been, though it has been turned into a triplex rental. When Jones and Ackerman bought it, in 1993, the home was wired for both electricity and gas, and the dual system remains in working order. They learned about the history of the house from a cousin of the Cayton family, who put them in touch with other family members. About the nomination, Jones says, “We feel like it was meant to be.”

A chance encounter between co-owner Ackerman, who was doing work on the property, and Taha Ebrahimi, a Seattle writer of Iranian heritage who works in marketing at a software company, catalyzed the nomination. Ebrahimi had come across a reference to the house in a history of Capitol Hill, where she also lives. She sought out the address and was amazed it was still standing — so many of the old wood-frame structures on Capitol Hill have been demolished for development. She says the Cayton’s story resonated with her because she grew up in one of the few families of color in North Seattle’s Windermere neighborhood.

Ebrahimi channeled her pandemic downtime into researching and writing the landmark nomination, a thorough summary of the history of the Caytons and their house.

A time of promise, eclipsed by racism

These days, Seattle is trying to come to terms with its history of racism and exclusion, forces that no doubt influence the way we understand and tell the history of ourselves. You won’t find the Cayton name, for example, in the indexes of the most popular Seattle history books. Perhaps one reason for this is that the family history reflects a time of promise for Black residents, which was ultimately overwhelmed by growing bigotry that erased parts of Seattle’s past from the broader community. The Caytons, in life and in history, have been victims of that trend.

Taylor, the historian, points out that in the city’s frontier period, Black business ownership as a percentage of the population was higher than it is today. Founders of the Black community before 1910 ran enterprises for a largely white clientele. William Grose, only the second Black man to live in Seattle, grew prosperous running a popular downtown diner and hotel, and by acquiring valuable real estate. Seattle at the time was a relatively small community. “Black people, somehow or other, were allowed to succeed,” Taylor said at a recent KCTS9 event. For some families, including the Caytons, the Far West was seen as a place freer of prejudice than the rest of the country. “There was a moment of hope,” Ebrahimi says. “It was the last stop.”

The Caytons did succeed. Horace’s Republican newspaper enjoyed wide readership — plus the support of many local advertisers — and the family prospered and grew. In addition to state and local political news, the paper featured commentary for the general community on its front pages and news of the burgeoning Black community on its inside pages (the Black population in Seattle grew from about 400 in 1900 to nearly 2,300 by 1910). In reading the Republican’s pages online, the voice of the Caytons comes through even now: modern in its concerns, rational in its response to events, generally optimistic and hopeful, and fearless in rendering judgments. It was a very good paper that holds up better today than most of its era.

The family did business as a commercial printer, too, including a stint printing for the state Legislature. Horace’s politics were mainstream for the times, though he was also an early and strong voice for Black equality and civil rights. Cayton formed a bridge to the successful white community as well. S. Leonard Bell wrote in a 1968 Seattle Post-Intelligencer story, “Residing in the then wealthiest area in Seattle, the Caytons employed a servant and owned a horse and carriage.” In 1909, Horace Sr. drove a visiting Booker T. Washington, in town for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, on a tour of the neighborhood, the so-called “Millionaire’s Row,” and Volunteer Park, which is just blocks to the north of the Cayton residence.

Cayton hoped this success could be a model for others, a means of showing how one could achieve access to power and influence through argument, example, and progressive politics. But as Seattle grew, Taylor says, the politics of the mostly white population replaced frontier-era tolerance with a social structure they were more familiar with, one that excluded African Americans.

Starting about 1910, a racist and exclusionary atmosphere took hold. Restaurants began to post “white only” signs. Housing covenants excluding people of color proliferated. And by the 1920s, the Ku Klux Klan was a wide-open presence in the city. At one point, Cayton sued a local restaurant owner for declining to serve him, but the suit backfired, damaging Cayton’s reputation when it revealed an earlier prison record in Kansas. In the 1880s he had been unfairly convicted of perjury in a court case involving his employer; after public outcry, Cayton had been pardoned by the state’s governor. In an effort to push back against the changing atmosphere in Seattle, Cayton became a founder of the local chapter of the NAACP.

The result of all this was the decline and fall of the Republican, which folded in 1913, according to Richard S. Hobbs, author of a biography of the family, The Cayton Legacy. Cayton launched a new paper called Cayton’s Weekly, a more personal periodical largely intended for the local Black community. Many white-run newspapers in the region criticized Cayton for pushing back against the lynching of Blacks in the South, Hobbs writes. He was accused of defending rapists and engaging in “attacks on ‘sacred white American womanhood,’ ” according to Hobbs. He was even criticized for standing up for better treatment for Black women in the South. “They attacked him with racial slurs, personal insults, and political innuendo,” writes Hobbs. Meanwhile, other local Blacks struggled to find economic opportunity, and the forced segregation of Blacks to the Central District began to take shape. The Caytons eventually moved there, too, from their place on 14th Avenue, due to their falling fortunes.

In 1918 the family came down with the Spanish influenza. They all survived. Their eldest daughter, Ruth, died in 1919. The Caytons took in her 1-year-old daughter, Susan, raising her as their own. Susan’s son, Harold Woodson, Jr. says he is “grateful and happy” the house is being recognized and plans to testify on its behalf.

‘A great, significant statement’

The Caytons’ arc from hopeful newcomers and successful businesspeople to a precipitous decline in their middle-class fortunes because of racist prejudice is tragic. But part of their extraordinary legacy includes two adult sons, Horace Jr. and Revels Cayton, both of whom lived at the 14th Avenue house and were raised and schooled in Seattle. Horace Jr. moved to Chicago, where he became a sociologist and co-author of a landmark book on the Black urban experience, Black Metropolis. Revels became an anti-racism activist and labor leader in the maritime industry on the West Coast. In 1934, as a member of the League of Struggle for Negro Rights, Revels Cayton led a demonstration at the Seattle City Council, demanding an end to housing discrimination. His civil rights work continued for decades.

The Cayton family had links to many major figures of their eras: Booker T. Washington, Langston Hughes, Paul Robeson, Harry Bridges, Richard Wright, Sinclair Lewis, to name a few. The influence of the Cayton family was felt way beyond Seattle.

In his preface to his book on the Caytons, Hobbs wrote that the “legacy of the Cayton parents and children is extraordinary — a human and American saga. Their story is a virtual mirror of the American past, showing our strengths and weaknesses, our glories and embarrassments.” The Cayton-Revels House on Capitol Hill helps tell part of that story.

Stephanie Johnson-Toliver, president of the Black Heritage Society of Washington State, says she thinks landmarking the Cayton-Revels House would make a “great, significant statement.”

On a separate track is a community effort, Friends of Cayton Corner, to work with the city of Seattle to create and name a green space park, on Madison Street and 19th Avenue, after the Cayton family. It’s a great idea, but the city can do more. It’s clear that through their life work, struggles and multigenerational family legacy, the Caytons left an indelible, if underappreciated, mark on Seattle that deserves recognition and remembrance.