John Okada’s Seattle-set novel No-No Boy, which was published in 1957 and nearly faded into obscurity before being revived decades later by the University of Washington Press, is a notable exception. And while the number of novels addressing Japanese internment is only increasing, true stories of refusal and rebellion are vital to the historic record and contemporary awareness.

That’s why the Wing Luke Museum assembled a team of two writers and two artists to create a book-length nonfiction comic about Japanese American resistance to the internment.

The writers — Seattle author and filmmaker Frank Abe and Tacoma author and historian Tamiko Nimura — had met before, but they’d never worked together. The artists, Ross Ishikawa and Matt Sasaki, had two completely different styles; Ishikawa was known for warm, cartoony realism while Sasaki tended toward strikingly expressionistic, nearly abstract, illustrations.

They were given a deadline of one year to work together to create a nearly 200-page, full-color comic that combined deep historical research and compelling narrative storytelling. Within that tight time frame, it felt like an impossible task. Partly because, well, it was impossible.

Now, four years later, Seattle publisher Chin Music Press has released We Hereby Refuse: Japanese American Resistance to Wartime Incarceration. It’s well worth the wait.

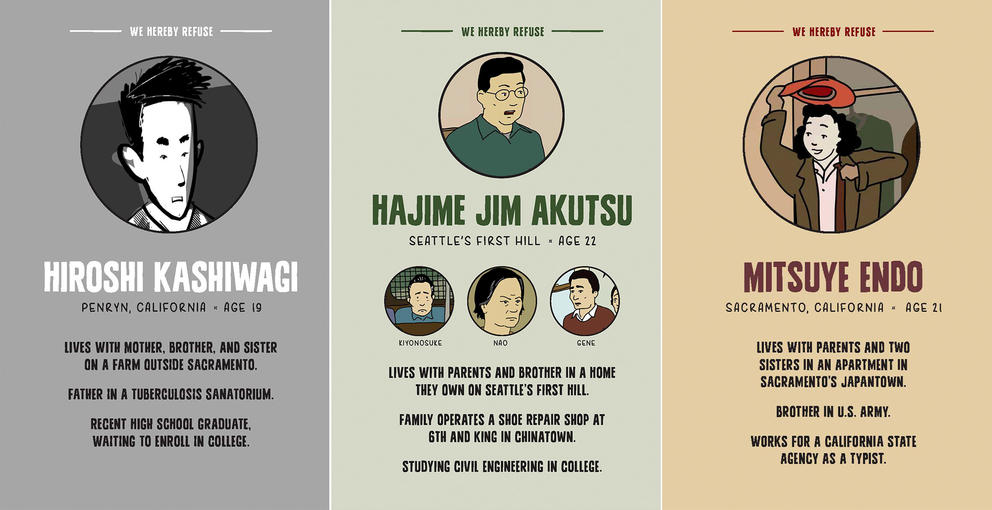

We Hereby Refuse braids together the stories of three Japanese Americans who resisted the concentration camps: Hiroshi Kashiwagi and Jim Akutsu, who refused government pressure to demonstrate their loyalty while imprisoned in the camps; and Mitsuye Endo, who agreed to sign her name to a lawsuit opposing the camps — one that would eventually go all the way to the Supreme Court.

These three protagonists weren’t directly connected in real life, but in a phone interview, Abe explains that he wanted to “weave their timelines together” so “the reader can experience the evictions and the incarceration on the same timeline as the characters.” Even though they never enter the same room at the same time, they live in the same continuum. A victory in one person’s story directly causes violent consequences for someone else.

Akutsu’s story has been adapted into a narrative once before — he’s the basis for Ichiro Yamada, the hero of No-No Boy. In many ways, We Hereby Refuse sits deeply in conversation with Okada’s classic novel. Abe has long championed Okada's work, and he relished “an opportunity to turn No-No Boy inside out and show the real-life events that informed the novel.” Okada even makes a small cameo in the comic — a fitting homage to the father of internment literature.

While a teacher’s guide and an online interactive timeline to accompany the book will be published this month, it’s a shame that We Hereby Refuse doesn’t come with an annotated bibliography to guide readers through the historical record. Abe and Nimura worked as hard as humanly possible to source the authenticity of every single piece of dialogue in every single word balloon.

Many lines — particularly the horrific statements made by white lawmakers and military personnel — are taken directly from the historical record. (“If an American-born Japanese is really a patriotic citizen,” California Rep. Leland Ford announced, “he can prove it by permitting himself to be placed in a concentration camp.”)

Other dialogue is pieced together from intensive research. Abe is especially proud of the way We Hereby Refuse reclaims the historic actions of Endo, who was “always an enigma — just a name on court briefs. She was a very private person.” Her part in fighting the legal battle against the internment camps was in danger of being erased from history altogether.

Abe’s decades of research into the internment resisters had uncovered only a couple of interviews with Endo, but Nimura, Abe says, “found a wonderful set of letters that she’d written to her attorney and an academic journal article written by the niece of her close friend, which contained a lot of personal details.” All those little scraps of details helped the writers give Endo an authentic voice and restore her pivotal role in the resistance.

Of course, none of this painstaking research and narrative development would matter if We Hereby Refuse was a bad comic. In the hands of an unskilled or inattentive artist, the best writing in the world is worthless. Thankfully, Ishikawa and Sasaki rose to the occasion, bringing the story to life in two very different ways.

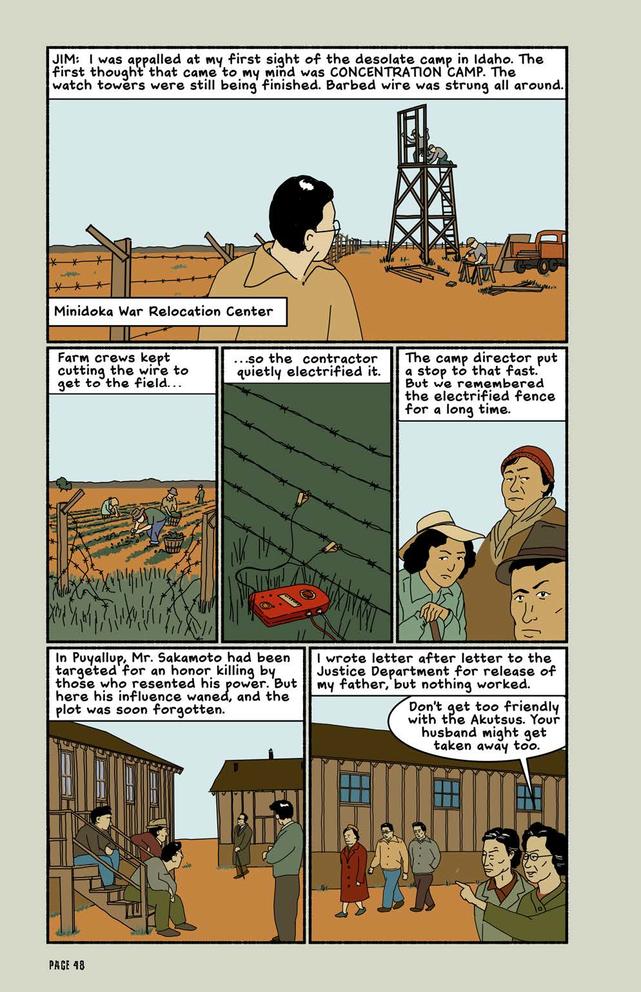

Ishikawa’s realism transports the reader to a pleasant home on First Hill, where federal agents find a Japanese-language magazine tossed in a trash can. They decide that’s enough evidence to strip the man of the house (a shoemaker with a modest shop in the International District) off to a detention camp.

Ishikawa imbues his characters with an actorliness that makes them immediately relatable, and he places them in thoroughly researched visual reproductions of camps, including a temporary detention center built on the Puyallup fairgrounds. This is the kind of emotive, detail-oriented art you expect to see in historical comics.

One wordless passage, in which a white prison guard suspiciously pulls apart a rice roll with his fingers while searching for contraband, conveys an unspeakable, brutish sadness that no amount of prose could capture.

Sasaki’s art, however, is something else again. Told mostly in angular slashes of black and white, with occasional sprays of red for dramatic effect, Sasaki’s storytelling is less focused on historical accuracy and more on emotional accuracy. His first scene in the book, when a police officer pulls over Kashiwagi in a traffic stop and — with no evidence — immediately accuses him of being a spy, feels paranoid and claustrophobic and more than a little terrifying.

“We had never seen a book where these two kinds of styles were put together in a single story,” Abe says. He credits the book’s designer, Dan D Shafer, with creating a consistent visual vocabulary that brings both artists together. Ishikawa’s passages, with characters’ shoulders slumping ever further as they’re shuttled from one dirt-brown cell to another, feel like documentary filmmaking. Sasaki’s id-powered fantasias put readers directly into the story, surrounding them with the same fear and uncertainty that the characters feel.

The collaboration “does give a kind of a textural layer to the story,” Abe says. “The camp experience was so multidimensional, with so many different perspectives, and the different art styles reflect the different ways of looking at a shared experience.”

While We Hereby Refuse honors the past and contributes to the small-but-growing body of work around the wartime internment of Japanese Americans, it has a lot to say about the 21st century, too.

At a time when anti-Asian violence is spiking around the country, when too many Americans are perfectly fine with the idea of caging immigrants with no regard for their rights, and when Black Americans fear for their lives during traffic stops, these stories still speak to the American experience. We tried as hard as we could to forget our past, but we should have known that the past isn’t done with us yet.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.