The press release from Sub Pop displayed the label’s typical cheekiness: “Striking while the iron is ice-cold and at least 6 ft away and most definitely masked-up, Sub Pop Records is expanding our retail empire.”

The diminutive space is filled with Sub Pop-branded T-shirts, coffee mugs, and even Sub Pop face masks, but it has shiny vinyl albums, too. Everything smells new and fresh, which makes it entirely unlike the record stores of my youth, all of which were cavernous, musky and stacked with “quarter” bins full of cheap, used LPs. Though I love the idea of a new record store — or any new store, given 2020’s closures — the whole place made me feel nostalgic.

It is far easier to catalog recently closed record stores in Seattle — such as Ballard’s beloved Bop Street, which went down this past summer, or Capitol Hill’s Everyday Music, which just announced it will close in June — than it is to name new locations. Most tend to be boutique scale, like Daybreak Records in Fremont, or Beats and Bohos in Greenwood. But there is also Sub Pop’s other location, which opened at the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport in 2014, and has been a hit with travelers. The press release for the South Lake Union store noted that you can now “visit a Sub Pop store” without risking “a cavity search to get in.”

Bruce Pavitt, who co-founded Sub Pop in the ’80s with Jonathan Poneman, stopped by the new Sub Pop shop last week. “Though it’s small, it has a deep collection,” he says.

And while Pavitt admits the new store doesn’t have the “punk vibe” of the record stores he grew up in, he says it will still serve as a ground zero of sorts for those who want to keep up on the label. “The person behind the counter at a record store is always key,” Pavitt explains. “That person will certainly be a source for information and be privy to Sub Pop things coming out that you can’t read on the Internet.”

I couldn’t read about or listen to anything on the internet when I was first discovering music — it didn’t really exist. As a teenaged college student in the late ’70s and early ’80s, I haunted Seattle’s record stores instead. There were at least a dozen on or near University Way: Discount, Music Land, Campus Music, Budget, Second Time Around, Tower, Cellophane Square, Peaches, and Uncle John’s (where I once found a pristine promo copy of a Velvet Underground’s debut for a dollar).

Back then, the closest thing you could find to a computer’s CPU or a website was the clerk sitting behind the record store register. That clerk often knew release dates, had band suggestions, and was sometimes able to offer a discount if I bought in bulk. And I always bought in bulk, though mostly from the used bins.

My memories of important record finds remain so visceral that in an instant, I can be transported back to the time, place and even weather of that moment. No memory stands out more than the first day of the ’80s, Jan. 1, 1980, when I walked into Cellophane Square on 42nd Street on an unseasonably warm day (the high was 52, the internet now tells me), and manager Hugh Jones was playing the Pretenders’ self-titled debut album. The record cost me $5.99, but Hugh gave me 50 cents off, the kind of pity discount given to poor college students. (I’m sure it comes as no surprise that I still have this album, stored in a plastic sleeve, and it is still in VG-plus condition after countless plays over the decades.)

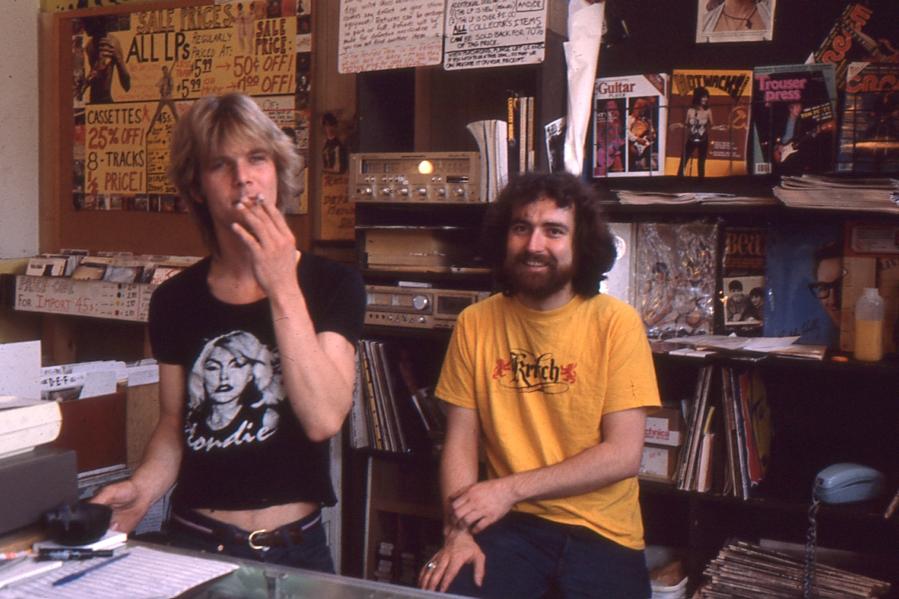

Hugh was one of the many record store clerks that I became friends with. Often they would put things aside for me with my name on them, if they thought it was my style. I’m still in contact with Hugh, who recently sent me a photograph of Cellophane Square from the mid-’80s. It shows Scott McCaughey (who played in the Young Fresh Fellows, Minus Five, and eventually R.E.M.) at the counter in front of a rare Beatles’ “Butcher” cover, and Garth Brandenberg smoking a cigarette and wearing a girl’s-size Blondie T-shirt. This was my life.

It is not hard to jump from this photo to a famous cinematic take, with Jack Black playing a record store clerk in High Fidelity. In that film’s most memorable scene, Black refuses to sell a Stevie Wonder single to a customer because it was “sentimental tacky crap,” and sends the customer to buy it at the mall.

You didn’t get much of that at Cellophane Square, where Hugh says he tried to “fight against the hipper-than-thou record-store attitude.” Still, I have to admit that I often selectively chose what records I bought at Cellophane, saving some of my more mainstream choices (like Kim Wilde’s “Kids in America”) for Tower Records. Today, this seems like totally insane consumer behavior, as I sometimes paid more at Tower than Cellophane. But I felt like the Tower clerks didn’t care what I bought.

I wasn’t the only one who made these crazy purchase decisions back in the day. Riz Rollins, longtime KEXP DJ and the very first person to ever play a Nirvana single on the radio, remembers how Michael Jackson’s Off the Wall changed his life. “It was the aural equivalent of crack,” he told me this week. “I wasn’t supposed to like it, but I did.”

But when Rollins had to decide which store to buy the Jackson album from, he picked Kmart instead of a local outlet. “I felt judgment from within and without [buying it],” he says. “It was on display behind the counter, but I didn’t even want to ask for it, so I went to the bin, and grabbed it, but also picked a Stephanie Mills album to hide the MJ under when I took it to the counter.”

When I researched Kurt Cobain’s life for my biography, Heavier Than Heaven, I was delighted to read in his diary that a teenaged Cobain bought his first album from a record store on University Way. He didn’t specify whether it was Cellophane, but the album was REO Speedwagon’s Hi-Infidelity (I would have bought this from Tower, though I wouldn’t have purchased that crap in the first place).

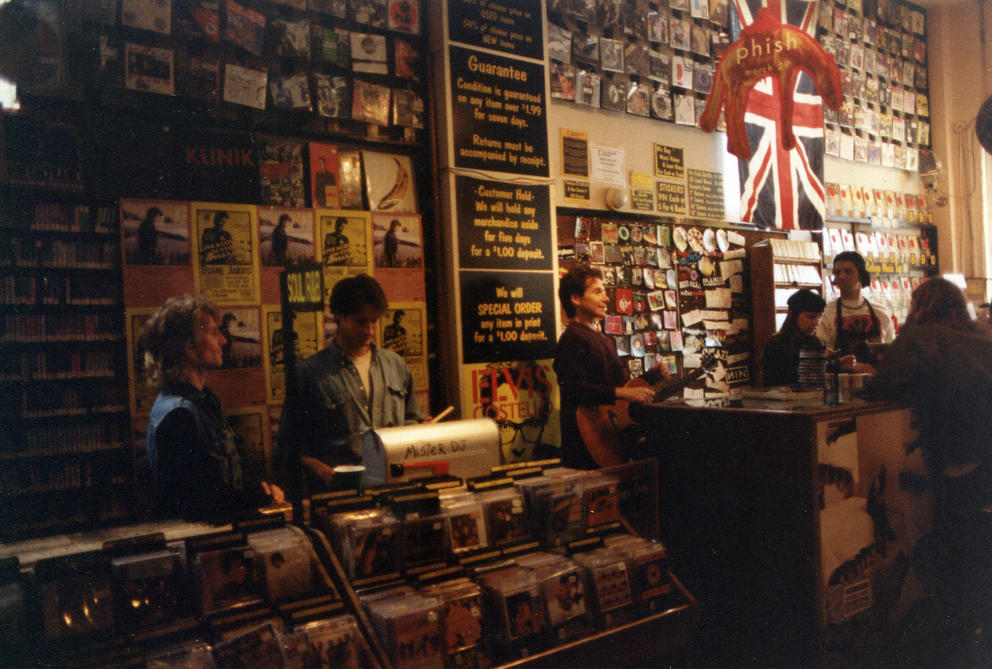

Kathy Fennessy was working at Cellophane in the ’90s, when Cobain, by then a star, came in. “He bought the Bats’ album, the Law of Things,” she recalled this week. “We all recognized him, but we let him browse. It was that kind of place.”

Mark Lanegan of the Screaming Trees was a frequent Cellophane customer (and worked at competitor Peaches for a time), as were the guys who would become Pearl Jam and Mudhoney. Carrie Brownstein of Sleater-Kinney gives Cellophane a shoutout in her memoir (as well as Bellevue’s Rubato Records). I think it would be harder to find a Seattle musician who didn’t shop at Cellophane during that era.

Sub Pop’s Pavitt grew up in Chicago and cites buying a Joy Division record at Wax Trax Records — the legendary store captured in a 2018 documentary film — as the moment that propelled him into what would become a lifetime in music. When he got to Seattle, he began shopping at Cellophane, attracted by cheap prices for used records.

The U District store played a more pivotal role in launching Sub Pop than has been previously reported: by hosting a record release party for the label’s first major release, Sub Pop 200, in 1988. The compilation album featured fresh cuts by Nirvana, Mudhoney, Tad and others. “We desperately wanted to get it out before Christmas, and Cellophane had this little party and display for us,” Pavitt said. “We didn’t even have supplies then, and Cellophane helped us rack up, seal, and box records, so it was a collaborative effort.”

Fennessy remembers coming into Cellophane that day and being surprised to find the entire Sub Pop staff, which then was just a handful of people, in the back room, sealing copies of Sub Pop 200. “At the time Sub Pop didn’t have a place to seal vinyl so they used our machine,” she says. “We had all heard about this record, with the Charles Burns’ artwork, and to see it in the back of Cellophane was a surprise.” Though other stores eventually carried the album, and sales of that record were extremely modest at the start, Pavitt says Cellophane’s early support helped the label stay afloat initially.

If you’re looking for the feeling of the Cellophane of old in a current store, I’d direct you to Easy Street in West Seattle. Matt Vaughan has run it since 1987, and often carries exclusive consignment sales from locals, much as Cellophane did in the day. He bought his first pivotal record — a Who 45 — at Fred Meyer, but later Cellophane became his go-to.

“The clerks at Cellophane had aprons with the store name, and they seemed to know everything about music,” he recalls. In homage to Cellophane, Vaughan recently designed an Easy Street Record jump suit, with pockets for cleaning supplies (and, as is pandemic-appropriate, PPE supplies).

Vaughan argues that the record store experience — interaction with the counter clerk, or discovering cheap gems in the used bin, or hearing unknown bands over the store sound system — just can’t be recreated over the internet. “It is the definition of community, which is an essential element to the Seattle music scene,” he says. “This is crucial to what Seattle is. We could be a city that just claims Starbucks and Amazon, but this city would prefer to be identified by music, whether that be Jimi Hendrix, Nirvana or Brandi Carlile.”

The past year has been rough for Seattle’s live music venues, but the record store owners I talked to, like Vaughan, say they are holding on. Most stores can accommodate patrons being 6 feet apart from each other, and some, like Tacoma’s Hi-Voltage, even offer curbside pickup.

Brian Kenney opened Hi-Voltage in 2005, at a time when most record stores were closing. But Hi-Voltage survived the past year, thanks to a robust online presence and loyal customers who want to make sure their beloved store doesn’t vanish. Kenney says “Record Store Day,” a nationwide promotion that started in 2007 and put exclusive releases into indie stores, helped. “We are in the ‘rediscovering vinyl era’ and RSD has been a huge part of bringing attention to stores again,” he says. This year’s promotion is set for June 12, when you can expect unique releases from Sub Pop, and others.

David Day runs Fremont’s Jive Time and says sales have remained steady this year. “People who are staying home have started to pay attention to their record collections,” he says. Just last week, the Los Angeles Times ran a story about the pleasures of “deep listening,” which is in a way a return to my experience as a college kid — playing entire sides of albums all day.

At Easy Street, business has been complicated by the pandemic closures of the adjoining restaurant. To offset those losses, Vaughan started doing house calls, delivering records. He made 900 trips before his van crapped out.

When Brandi Carlile and her band heard about that, they donated their 2005 Chevy touring van to Easy Street. “If there’s anything that shows you the love Seattle has for a record store, it’s that,” Vaughan says with emotion.

Vaughan’s been using the pandemic time to remodel, adding a “vinyl” bar to his store. He’s eagerly looking toward a future when Pearl Jam can once again play an in-store before a packed crowd. “We are not giving up,” he says. “Seattle music is not giving up.”

Most of the record stores of my college days, including Cellophane Square, did give up, as digital downloads and file sharing eventually destroyed much of the retail record business. The 2015 documentary All Things Must Pass about the rise and fall of Tower documents how even the largest retailers couldn’t compete with “free.”

Cellophane started at 42nd Street, but eventually moved three blocks north on the Ave. In 2000 the store was taken over by a larger chain, and by 2005 it closed for good. The upper University Way location is now a Korean Tofu restaurant, while the original, where I bought my beloved Pretenders album, is now a Vietnamese joint called Sizzle & Crunch — which, by the way, would be a kick-ass name for a new record store.

Sub Pop has so far defied those odds, but the irony of its new location — in a building that houses Amazon offices — is not lost on anyone paying attention. Still, the Sub Pop press release plays it true: “We mean to represent these artists as faithfully and diligently as possible and hold out hope that this is enough for us to remain solvent in the face of the well-documented collapse of the music industry at large.”

The label’s joke motto has long been “Going Out of Business Since 1988,” but it has survived 33 years. (Sub Pop’s 30th anniversary party — which was free and drew thousands to Alki in August 2018 — might represent the absolute apex so far of live music in this city, with the best vibes, best music and best crowd of any Seattle music event I ever attended. It was just perfect.) If I were going to bet on any single Seattle music artifact lasting until 2121, I think I’d bet on an iconic Sub Pop T-shirt.

As for record stores, I continue to hunt in their bins, always in search of a new favorite crush that will change my life — as Joni Mitchell did, as Bob Dylan did and as Sub Pop’s own Nirvana did. Every record store that closes takes a little piece of me with it, and every one that opens, even a tiny Sub Pop storefront, gives me hope.

Years ago, when Tower Records was going under, I grabbed one of its record display racks out of the trash heap. I’ve cleaned and repainted it, and so a bit of a Seattle record store lives on in my living room. After I finish writing this story, I’ll grab an album I always keep up front in that rack and put it on the turntable. As soon as that Pretenders record gets to Chrissie singing “Brass in Pocket,” everything will seem right with the world.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.