I was one of many Americans attempting a facsimile of work yesterday during the insurrection against democracy. I tried to focus on Northwest arts, tried to prognosticate what the new year might hold for a community that COVID-19 has turned upside down. But with alarming images from the Capitol flooding my feeds, the Seattle artist that seemed most relevant and innovative was one who died 50 years ago.

Jimi Hendrix performed one of the most iconic guitar solos in music history on Aug. 18, 1969. The place was, of course, the legendary Woodstock music festival in the Catskill Mountains of New York. The song was his electric take on “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

While I’ve heard the recording many times over the years, it had been a while since I really listened closely, so yesterday I pulled up the clip on YouTube. I encourage you to do the same, even if you’ve seen it before, as the performance feels almost destined for this historical moment.

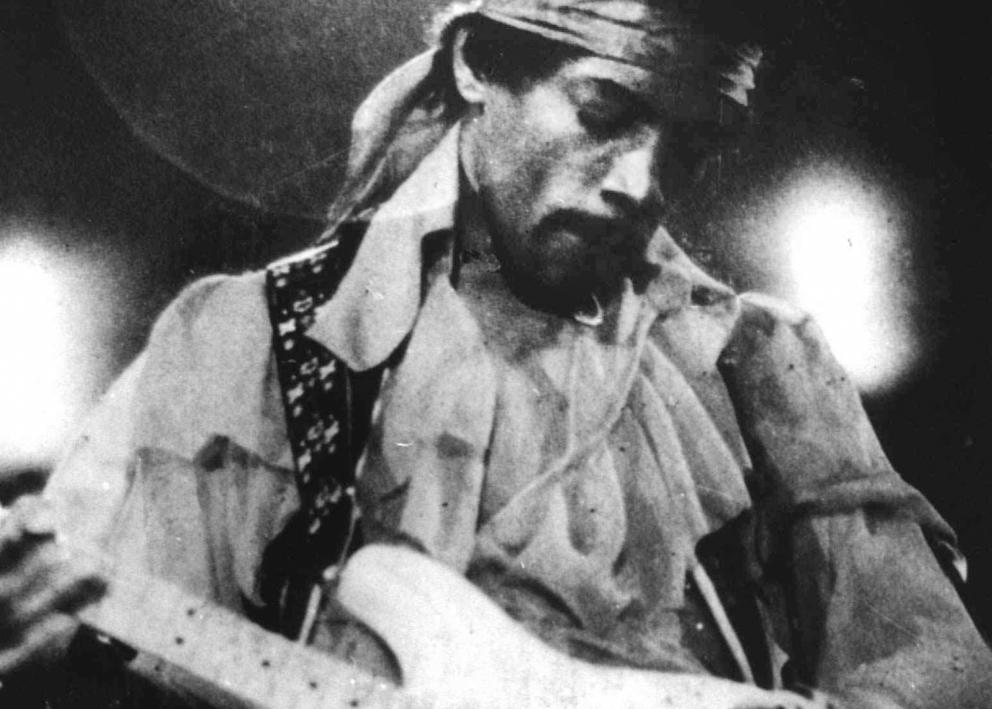

There he is, a mixed-race kid from the Central District, now an Army vet resplendent in a red headband, white-fringed jacket and blue bell-bottom jeans. The song is transcendent from the get-go, the first six notes of Francis Scott Key’s composition emerging as a clear and singular voice (“O say, can you see”) from the churning commotion of an improvised jam just before. The anthem was one of the last songs in the set, spontaneous — and one of the final songs of Woodstock, which Hendrix closed, on Monday morning after many thousands had already gone home.

People often characterize his take as “psychedelic,” but on this listen — on this day — what stood out to me was how studied it was. While legend has it the piece was entirely improvised, Hendrix scholars say he’d been working on adaptations of the anthem long before and had performed several dozen other versions already. But this is widely acknowledged to be the best, in part because of the cultural moment it so perfectly captured: young Americans gathering in the name of peace, love and music after years of battling for civil rights and amid protests against the Vietnam War.

Hendrix sometimes called his anthem adaptations “This Is America.” The Woodstock edition is almost straightforward — albeit on a Fender Stratocaster, an American innovation itself — until he reaches “the rocket’s red glare.” That’s when it rips open to reveal the pain and suffering of a nation at war with others, and within.

Distortion. Feedback. Screeching. Hendrix employs his trademark techniques and also replicates the sonic soar of fighter jets, ambulance sirens, artillery fire, combat cacophony and, yes, bombs bursting in air. At one moment he morphs the solo into “Taps,” the melancholy bugle melody that emerged during the American Civil War. He holds the note on “(o’er the land of the) free” for an extended scorch, then resolves the piece with ascendent power chords, triumphant.

In just under four minutes, he completely deconstructs and reconstructs a treasured emblem, and does so with compassion for a broken nation. It might be the most American thing I’ve ever heard.

Was his version patriotic or a protest? I’m certainly no Hendrix expert (for that, look to Crosscut contributor Charles R. Cross), but I know the subject has been long debated. Like America, it’s complicated. Hendrix served in the U.S. Army, earning his “Screaming Eagle” patch in the 101st Airborne Division. He voiced support for troops. He urged peace both verbally and with the V-sign in so many photos.

“I’m an American, so I played it,” he told Dick Cavett on a talk show one month after Woodstock. He pushed back against Cavett’s labeling of the performance as unorthodox, saying, “That’s not unorthodox…. I thought it was beautiful.”

In another widely quoted interview, he explained his Woodstock anthem as such: “We’re all Americans…. It was like, ‘Go America!’… We play it the way the air is in America today. The air is slightly static, see.”

In other words, Hendrix was doing what great artists always do: translating the culture and politics of the day into the language of art, so we can see it more clearly and feel the resounding chords of personal impact. His prescient performance rings even truer today.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.