From fashion designing to mask-making

One of the most obvious, literally in-your-face pivots we’ve all made? Wearing masks on a daily basis. Early on in the pandemic, a group of enterprising local crafters and laid-off costume makers didn’t wait for mask mandates. Responding to the dire shortages of personal protective gear on the medical front lines, Seattle crafters convened in virtual sewing circles to fabricate and donate thousands of homemade masks to local homeless and other organizations. Since last March, the Crafters Against COVID-19 Seattle Facebook group (now a nonprofit called Crafters United) has given out more than 100,000 cloth masks to some 150 local organizations and groups, including the Seattle vaccine trials at Fred Hutch, the Monroe Correctional Complex and Yakima migrant farm workers — and it’s still going strong.

As masks became de rigueur, local fashion designers embraced face coverings, which also helped sustain their struggling businesses. Even the art world, usually leading the pack when it comes to new trends, jumped on the bandwagon. This fall, the brand new Museum of Museums elevated the cloth face covering to an art form with an exhibit titled “Mask Parade.”

From the proscenium to the park

The year 2020 brought many surprises, and for me, one of them was finding myself crying in my parked car while a person in a yellow outfit danced with a balloon just beyond my windshield. By then (early May), Seattle performing arts venues had been closed for weeks, with artists going without gigs and audiences starved for art outside the screen.

Enter Cooped-Up: Drive-in Dances for Cooped Up People, the cutting-edge dance experiment by local company LanDforms, performed in April and May. Guided by pins on a map and a downloaded soundtrack, audience members drove through the city to a series of unusual performance venues. Once parked, viewers watched from their cars as dancers used their own balconies, yards and windows as a stage. The makers, Leah Crosby and Danielle Doell, have since staged an updated version of the performance (in which one dancer performed a moving pas de deux with her house plant). Keep your eye on their website for new material in 2021.

In the summer, local dance company Whim W’Him brought choreography to Seattle parks. During outdoor pop-up performances of The Way it Is, dancers spaced 6 feet apart moved forward in procession — a trick to ensure the audience didn’t congregate — dancers twirling, whirling, ducking and jumping on and on, as parkgoers perked up to watch.

We also got a glimpse into dancers’ interior worlds: literally Zooming into their houses, where they pas-de-bourréed across living rooms and rolled on shaggy rugs, all in the name of dance classes (from ballroom to ballet and “Dance Church”), rehearsals and performances at home. The Pacific Northwest Ballet staged a beautiful section of its canceled show One Thousand Pieces with dancers performing alone, in apartments, hallways and outdoor spaces, wearing sweats and street clothes.

PNB, Whim W’Him and the Seattle Dance Collective also took the offstage opportunity to premiere some excellent dance films. Thanks to the 360-degree close-ups, surprising locations and strong cinematography, these transported us to other places, made dance accessible to more people and brought something new to the art form that we hope is here to stay.

From strings to streaming

By mid-March, the cascade of concert cancellations due to bans on gatherings had morphed into an avalanche. The sudden loss of work dealt a huge financial blow to musicians relying on live gigs.

Some local organizations were determined to help artists crawl their way out of the snowpack by way of livestreamed concerts. Seattle music and event nonprofit Artist Home launched a virtual concert series titled “Songs of Hope and Healing” to help musicians recoup lost income. As Crosscut contributor Alexa Peters reported at the time, living room concerts, some with virtual ‘donate’ buttons, boomed in the first weeks of the pandemic.

From anyone wanting to tune in from anywhere, browsing the myriad options felt like looking at a music festival lineup. Seattle musician Erin Jorgensen got our senses tingling with marimba concerts on Sunday mornings (her “Marimba Church” is still going weekly, by the way). Death Cab for Cutie frontman Ben Gibbard went “Live From Home” daily (and later weekly) for 2.5 months with his guitar, benefiting various local orgs in the process. Local pianist Marina Albero kept the creative juices flowing with “The Quarantine Sessions,” while Seattle musician Tomo Nakayama promoted his new record, Melonday, online. Local musician Gordon Brown debuted a new streaming platform called Live Concerts Stream, and a team of artists worked on a “Netflix for local performances.” KEXP radio DJ John Richards started broadcasting live concerts from his front yard, featuring local musicians — and chirping birds chiming in as a new kind of accompaniment.

But the quickest and most impressive musical pivot came courtesy of a 117-year old institution: the Seattle Symphony Orchestra, which proved itself a vanguard by streaming free, previously recorded concerts as soon as coronavirus precautions set in. When the pandemic first closed the doors of Benaroya Hall on March 11, the symphony moved fast and broadcast a previously recorded performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 1, for free the next day — the first of many free livestreams.

In September, the symphony made waves again with a fall season opener like no other: a drive-in symphony. Arts & Culture editor Brangien Davis wrote about what it was like listening to Mozart’s “Overture to Don Giovanni” from the safety of shiny metal boxes parked in neat rows as a smaller but still impeccably dressed orchestra performed on stage — masked and spaced 6 feet apart in front of the auditorium’s 2,500 empty seats.

From big screen to small screen

The adage “what is old is new again” turned out to be the motif for the film world this year.

Even the already-vintage local video rental store Scarecrow Video went old school early on in the pandemic by testing out a “new” video rental and return program with help from the good old U.S. Postal Service.

Drive-in movie watching (as our Arts & Culture editor described it: “that nearly extinct relic of 1950s car culture”) also made a comeback. Inflatable and portable screens popped up all over, from the parking lot at high-end Canlis Restaurant to the lower Queen Anne location of performing arts organization On the Boards, which hosted a four-day film festival in October.

Speaking of film festivals, the small and nimble Northwest Film Forum quickly moved programming and various ticketed film festivals online when the pandemic hit, which has expanded its viewership for “seemingly niche and regional festivals” exponentially, NW Film Forum’s artistic director Rana San told me over email recently.

The team expects to keep its programs online even after reopening its physical Capitol Hill space, the forum’s executive director, Vivian Hua, told me in May.

“We've learned in this time that there is a need [for] highly curated programs well outside the city of Seattle, and that virtual cinema creates access for some who may otherwise not easily be able to go to a cinema,” Hua added in a recent email.

Northwest Film Forum’s pivots appear to have paid off. The influential Sundance Film Festival recently announced it has chosen the small Capitol Hill nonprofit as its only Washington state partner for the festival’s 2021 edition, facilitating customized local programming (talks, events, artist meet-ups), as well as new feature film screenings.

From the page to the digital stage

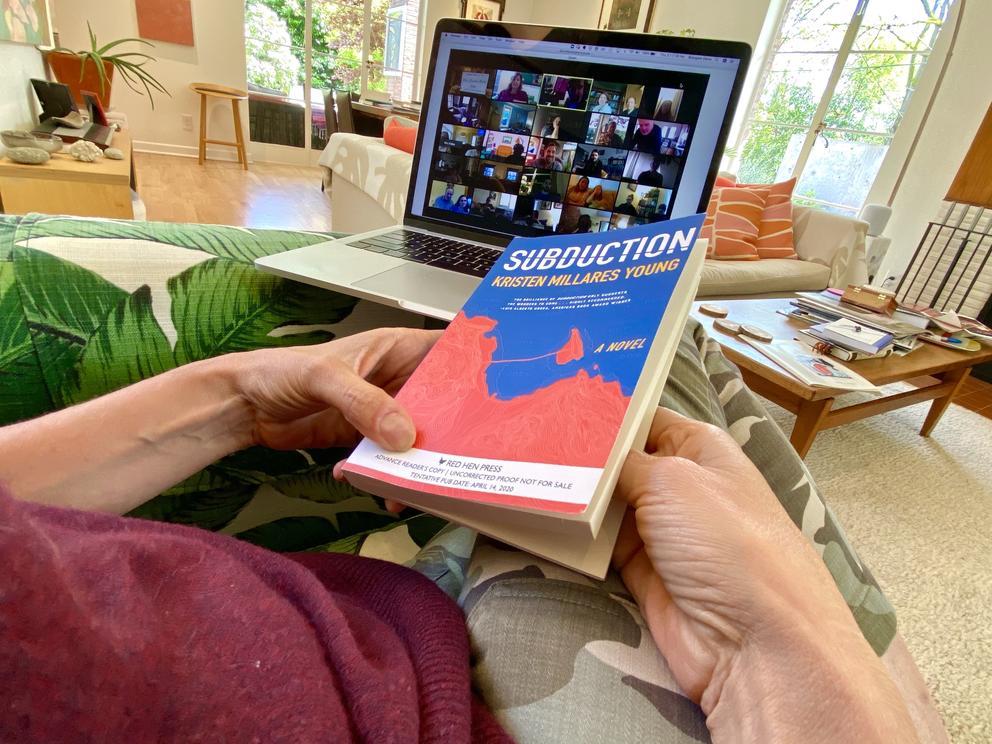

Writers may have a reputation for reclusiveness, but 2020 was all about the literary scene coming together in community — writing and reading all alone, together.

Washington State Poet Claudia Castro Luna created a web forum called Poems to Lean On for people to submit the poetry that got them through isolation. As Seattle’s Silent Reading Party moved from its Hotel Sorrento Fireside Room to Zoom digs, attendance soared. Ticket sales quintupled in its first online session, according to event founder Christopher Frizzelle, with celebrated guest authors and the New York Times in attendance.

Hugo House also made a successful switch to virtual literary get-togethers. While its shiny, still-new-feeling Capitol Hill home remained deserted, the beloved literary center helped many writers come out of their shells with writer-hosted Solitude Social Club happy hours.

Also proven popular at Hugo House: a new Quarantine Write-In series with Rebecca Agiewich (now led by poet Naa Akua); and, in partnership with the Seattle Public Library and Seattle Writes, the hourlong “Write With” sessions, a free drop-in writing circle for all ages and genres of writing. In both cases, local authors tease out a prompt and leave space for solo writing, the result of which attendees can share in “a mutually supportive, welcoming environment.”

Local indie bookstores brought the community together, too. Longtime customers picked up books at curbside (online orders sometimes came with sweet notes of support), attended virtual readings and signed up en masse for literary subscriptions boxes.

“Authors have been very, very supportive of us, too, ordering books from us and reaching out to their followers on social media,” added Elliott Bay Books’ Karen Maeda Allman recently. She mentioned Jeff Vandermere signing postcards with special messages for customers, Maria Semple giving bookstore gift certificates away on her social media, as well as a long list of authors like Molly Wizenberg, Pam Mandel and Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore urging people to order their books through the shop.

Virtual author events surged in popularity, too. Seattle Arts & Lectures is grateful for the “forced” digital innovation. People with disabilities and homebound bookworms now have access to lectures, along with anyone anywhere in the world. Plus, says Rebecca Hoogs, the organization's associate director, “We have heard that BIPOC audience members may feel more comfortable coming to a SAL event when attending doesn’t require entering a traditionally white venue.”

One, perhaps unexpected boon: a new kind of intimacy you can’t get in a huge venue. “The viewer and the author are face to face. The audience is a witness to one person speaking, or two people having a conversation. You can see every facial expression. It’s strangely (and wonderfully) almost a more vulnerable space,” Hoogs says. “Though we are distanced, the distance is also removed.”

From the stage to the ears

The 3D magic of live theater just doesn’t translate to the computer screen, so 2020 became the year of theater for the ears.

In Seattle, the coronavirus sparked a revival of an age-old art form: the radio drama. With venues still closed, actors out of work and people tiring of Zoom events, Sound Theatre, Book-It Repertory Theatre, Seattle Shakespeare, The 5th Avenue Theatre, ACT and Seattle Public Theater all reshaped or staged new plays in audio format, streamed via the internet rather than the airwaves, including Richard III, the Indigenous-futurist Changer and the Star People, Octavia E. Butler’s Childfinder and the still-to-debut Himalaya-set musical Half the Sky.

Local performing arts organization On the Boards took the audio idea one step further, staging a series of live phone performances for intimate audiences of two as part of the U.S. premiere of the theater experiment A Thousand Ways. Along with a stranger, I signed up for an hourlong phone call, which unspooled as part-questionnaire, part-acting session (we were instructed to read lines and answer questions) that made me feel simultaneously closer and further away from people than ever — but mostly, excited about theater again.

On the Boards was one of Seattle’s most thrilling performance pivoters this year: The small and inventive org took artistic risks few others in the region attempted. In addition to the phone performance, the company orchestrated a socially distanced play with strangers and hidden cameras (the resulting film, Acting Stranger, screens Jan. 26), and has more exciting stuff in the works, including a 360 degree virtual reality performance by Seattle-based dance and visual arts team zoe | juniper.

From the canvas to the street

COVID-19 temporarily closed countless visual arts venues this year, but painting and sculpture were more accessible to the public than ever. Suddenly, art was everywhere, even in the street.

Yes: We’re talking about the unmissable blocklong Black Lives Matter street painting by local arts collective Vivid Matter on Pine St. on Capitol Hill, the heart of protests against systemic racism and police brutality this summer. Created quickly in the heat of the protests, the mural has been repainted to last.

Also making a pivot from canvas to a new medium were countless artists sending messages of support and protest on the plywood covering the city’s closed-up businesses. (Much of this artwork was captured for posterity in the book Viral Murals: Seattle Artists, Storefront Murals, and the Power of Art During Crisis, and on the Brush of Seattle website.) Poster (protest) art was present in full force, too, thanks to artist Monyee Chau and the Seattle-based nonprofit Amplifier, among others.

Some artists made public work digital: local art duo Electric Coffin projected large-scale balloons with messages such as “We will not desert you” on the blank sides of buildings. An augmented reality exhibit projected digital protest art into the sky (via your phone screen). We’re betting virtual public art will continue into 2021 and beyond.

More outdoor art viewing options came from artists who opened their own art spaces during the pandemic, including the window-only exhibition space Das Schaufenster in Ballard, and King County’s newest and tiniest art space: Sun Spot, a white box on a wooden post on the northern edge of Des Moines. We covered those innovative new art spaces earlier this fall, along with other pandemic-inspired galleries: one that was purely for the ‘gram (aka Instagram only) and another livestreamed twice a week from a North Seattle house via Twitch.

Also in the category of armchair artgoing: Plenty of interesting virtual art viewing options popped up this year, including entertaining video tours of the Bellevue Arts Museum collection with Executive Director Ben Heywood (boasting a British accent and a totally accessible way of talking about art), as well as “By the Hour,” a digital conversation and tour with local artists and Pioneer Square gallery owners.

Meanwhile, some creatives went so far as to build digital 3D gallery models (think The Sims, but for art). The Georgetown-based Studio e created a “Virtual Venetian” fantasy gallery for the first-ever edition of the Seattle Deconstructed Art Fair, another coronavirus-era pivot in itself. Also check out BAM’s nifty 3D tours, and this impressive online exhibit by local artist/curator C.M. Ruiz about U.S. intervention in Guatemala, which feels very much like wandering through an old Pioneer Square gallery space.

Last but not least: the prize for most anti-establishment pivot this year goes to New Archives, a local art magazine launched right before the pandemic. It switched from covering work by contemporary artists to asking people to write about the art on the walls (where else?) at home.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.