Created by Lynnwood-based Japanese artist Fumi Amano, the exhibit is called Resilience, and is part of the city of Auburn’s Art on Main public art project (viewable through Jan. 3). The differences in the two sculptures reflect the range of Amano’s recent body of work, in which she deconstructs and repurposes old windows to create pieces that reflect on topics from Japanese internment to racial identity to cultural expectations placed on women.

Amano’s wide scope of creative output has also included performance art. In one piece, she set up a treadmill on the median of a busy intersection and broadcast her fears — about being 30 and unmarried — from a bullhorn. In another, One Night, she re-created her bedroom in a gallery space, laid a life-sized jelly mold of her boyfriend on the bed and proceeded to eat it sloppily. (“I once had a dream that I ate his entire body,” Amano writes in her dissertation.)

Such experimental artwork is exactly why the 34-year-old Amano (now married) immigrated to the U.S. in 2013. (Her first visit to the States was for a workshop at Pilchuck Glass School in 2009.) Trained as a traditional glass blower at Aichi University of Education in Japan, Amano felt a strong urge to transition from craft artist to conceptual artist, which she explored while pursuing a master’s of fine arts at Virginia Commonwealth University, where she graduated in 2017.

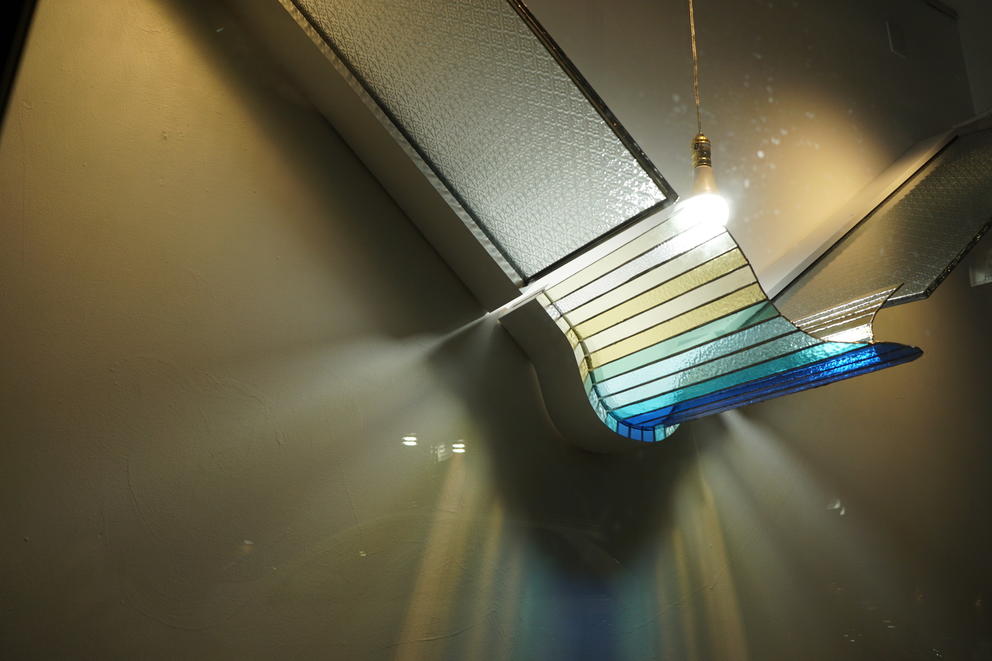

Since moving to Seattle in 2018, she’s retained her experimental spirit, but returned her gaze to glass. Her clever reinterpretations of windows and frames, which she sometimes calls “glass houses,” have appeared at Pilchuck Glass School’s Pioneer Square gallery, Bellevue Arts Museum, INSCAPE Arts, and Shunpike’s Storefront window series in South Lake Union. This fall, one of her glass houses was selected for an installation at the Winslow Wharf Marina on Bainbridge Island (on view until June 2021).

For Amano, the windows represent looking back on memories, missing her home country and feeling distanced from others by linguistic and cultural barriers. But she says since the arrival of COVID-19, she has wanted to bring more hope to her work.

“After the pandemic [hit] I didn’t want to see my dark side,” she says. “I wanted to see the future.”

Crosscut spoke with Amano about feminism, glass art in Japan and her experience as a recent immigrant to America.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

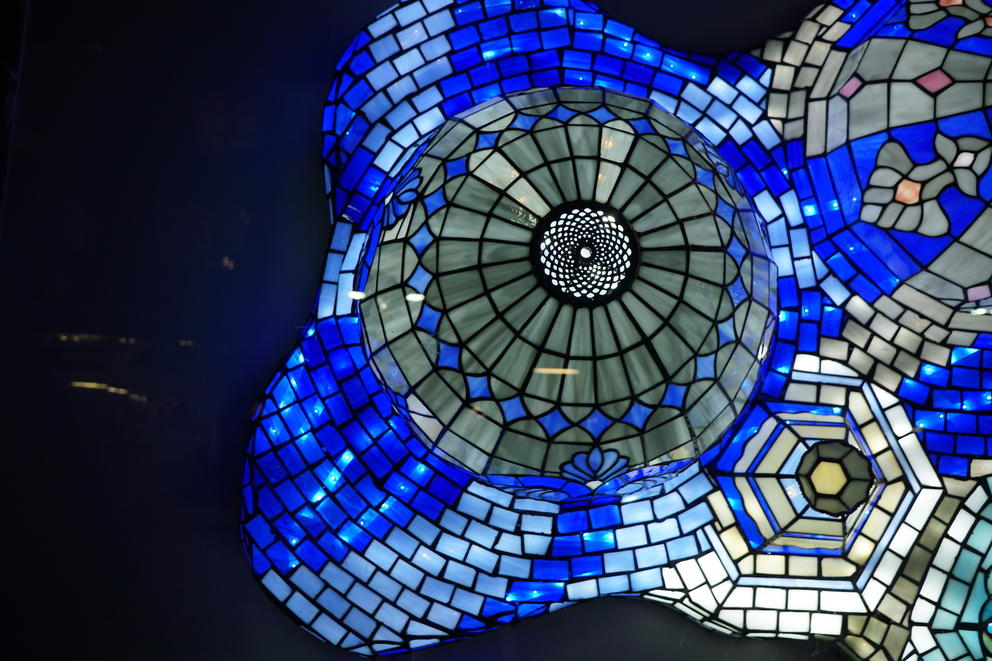

Fumi Amano mended shards of found stained glass to create “Blue Sun,” which she says is a metaphor for the pandemic. “Everything has changed in 2020, something we’ve never seen has happened,” she says. “In my mind that’s a blue sun. It’s never happened, but it’s happening.” (Agueda Pacheco Flores/Crosscut)

Tell me about the two glass pieces in Resilience, on view in Auburn.

I started that project when this pandemic started. I had a different concept for the installation last year, but the pandemic changed my mental condition and physical art practice a lot. I stayed at home like everyone did. I was looking for what I could do, and I started this mending project with broken pieces of stained glasswork. I found a lot of stained glass lampshades on eBay or Craigslist, and I collected those to mend together.

Is that why you named it Resilience?

I didn’t know that word before the pandemic. But I’m working for Pratt Fine Arts Center right now as a glass studio manager.... Pratt is doing a campaign called “Creative Resilience,” a donation campaign [asserting that] we have the power to heal from this crisis with creativity. I really love the concept. To me resilience is like a healing process, like a recovery from some bad situation. And the mending process of stained glass was a healing process while I was staying at home.

How did you get started as a glass artist?

I started working with glass when I was an undergrad in Japan. It was fun and fascinating — the process of blowing glass. [But] in Japan, the craft is more traditional. There are so many restrictions. I felt like the craft should be more about issues or life. I wanted to be more free, to learn some different perspectives in glass. That’s why I moved to the U.S., to see what I can do with glass.

What’s the message you’re conveying with the use of old windows?

I've been working with window frames to build sculpture for my work since 2016. At that time, I was not happy. I was in Virginia in grad school, but I was alone in the city. I felt like I had distance from people. That glass house project started since I felt invisible filters between people. I used glass as a metaphor — windows divide people. And then, using old material — old window frames have all kinds of scratches or some scars. That is also a memory of someone. That helps me feel like I’m connecting with people. That's why I really like using all the window frames to make sculptures. People can see me and I can see people, but we cannot touch each other because of the glass.

How does using found stained glass shift your work?

I found it appealing that I could create something that I thought was beautiful from materials someone else had thrown away. It felt like I was giving a second life to garbage. Due to the pandemic, instead of making large-scale sculptures, lately I’ve been making a lot of smaller stained glass pieces … and glass plant stands. They don’t require a lot of space and are easy to manage at home. Rather than creating beautiful stained glass work from scratch, I’ve found myself becoming more and more interested in the process of mending recycled stained glass.

Your past work has explored the societal pressures of being a woman. Was that theme present in your work in Japan, or did it arise once you came to the U.S.?

Yeah, a lot of my performance work and some glass sculpture work [engages with] the concept of feminism. Before I came to the U.S. I wasn’t thinking about who I am or what I was doing, because Japan is a monoculture. I didn't feel much different about my identity. But when I came to the U.S. I had a lot of opportunities to ask who I am. Then, because the president changed, the political situation also made me think about feminism a lot. In January [2017], I was in Virginia, so I drove up to Washington, D.C., to join the Women's March. It was really, really big. The unity I [experienced] was a big transition about how I should think about my feminism.

How did being in the U.S. change your perspective?

In the United States, I wasn’t just an individual woman, Fumi Amano. I was recognized as an Asian woman. That was a shock to me because in Japan it never happened. Everyone is just a Japanese woman, and we didn't seem that different. But in the United States, it's different... I had to learn the history of the Asian woman in this country. That's why 2017 was a big year for me to think about who I am as a woman.

What was your experience as a woman in Japan, and how does that compare with your experience as a woman in the U.S.?

In Japan there’s more interference by parents for middle-age women. Parents are worried about their daughters getting married by the time they turn 30. They're really anxious about it. But at the same time in the U.S. there are stereotypes for women and Asian women, too: “Asian girls are so easy. They don’t say anything.” That’s what I felt from men in the United States. I have to be pretty strong. I have to be tough to survive in this country.

When did performance become part of your practice?

I'm shy and [initially] I was not interested in performance — I was crying when I did my first performance at school. But I got into performance in 2015, when I turned 30. My frustration with communication and frustration with my relationship with my boyfriend, all of the frustration in my mind was not dissolving. My English was really bad and my relationship was not good. But in the performance, I'm the one being a sculpture to express my feelings — that was a direct communication with viewers. I felt like, “OK, for a couple months this is the only way I can communicate with people.” That’s why I started performing. Mostly the performance was about either communication or feminism or intimacy.

How has the pandemic changed your view of intimacy and connection?

The pandemic changed me a lot, physically and also mentally. During the pandemic I got married, with that same boyfriend — we finally got married. So, yeah, since the pandemic, people think about relationships a lot. Some couples broke up, but some couples, like me, got married.

What’s married life like during the pandemic?

I was going to have a performance in New York called Getting Married with America. Right now, the visa process for foreigners is very slow because of Trump. To get married to Americans we have to collect all the documents, almost 100 pages of paperwork we have to do. And they determine the amount of time I have to wait to get a visa, a green card. It takes so much time and money. There’s so much to do just to get married because I’m a foreigner. The current political situation is not kind to foreigners. We are not welcome.

How do you imagine the art scene will come out the other end of this pandemic?

Our industry is so tough, so tough. Lots of big galleries are struggling right now, but at the same time there’s lots of relief funds from organizations. [Originally] I thought “OK, America, I have to win. We have to compete with each other to win.” But right now we are sharing with all the artists who need help. So that is how it’s changed.

Get the latest in local arts and culture

This weekly newsletter brings arts news and cultural events straight to your inbox.